Soandry del Rio and Hip-Hop Cubano

by Joshua Barnes / January 18, 2011 / 2 Comments

Fists pump the air. Flashing lights dance across the jostling crowd, and a rapper steps out on stage. His delivery is smooth: he is a virtuoso with rhyme schemes and tightly packed wordplay, and the crowd responds with cheers. But while his music will seem familiar to any American hip-hop fan, this musician isn’t from New York or Los Angeles. He’s from Havana, Cuba.

Soandry is a rapero, a socially conscious rapper from the growing Cuban hip-hop scene. After being included on the 2002 compilation “Cuban Hip-Hop All-Starts: Vol. 1,” he became more widely known in Cuba. He was also featured in the 2006 documentary East of Havana.

In late October, he had his American debut at the New Hazlett Theater in Pittsburgh, as part of a residency sponsored by the Mattress Factory Museum, which is currently hosting the exhibition Queloides: Race and Racism in Cuban Contemporary Art.

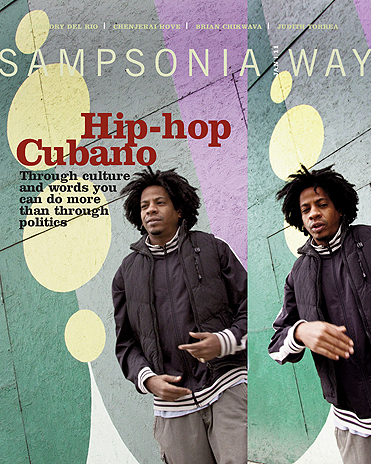

Soandry is tall, with a cloud of black ringlets and a row of gold teeth that can be seen on the rare instances when he smiles. He speaks with an uncommon intensity, whether rapping on stage or talking off-stage about the history of Cuban hip-hop.

He described why American rap was so poignant to Cuba’s youth since its beginnings: “Hip-hop resonates with people who need hope, people who don’t identify themselves with any of the rhythms that were available before hip-hop came.” When Soandry heard American rap for the first time, it was a revelation: “Suddenly there were guys like me, making music with language like mine, with struggles and experiences like mine.”

“You need to have good lyrics to make people stop dancing and think.”

Hip-hop first came to Cuba in the 1990s via pirated radio from Florida. During that decade, illegally taped copies of the show Soul Train started to circulate underground. Albums from artists like Notorious B.I.G., TuPac, N.W.A., and Public Enemy were passed from hand-to-hand by impoverished Cuban youth.

According to Soandry, at the beginning of Cuban hip-hop even ambitious raperos couldn’t make complicated tracks. There were no CDs, no mixers, no multi-track recorders available on the island. The only way to make a track was to record the last few instrumental bars from the end of a pirated song onto a cassette and loop it for three or four minutes to make a beat. Using a dual cassette recorder, artists would record vocals onto another tape while the loop played in the background. With time, recording equipment was brought into Cuba from the States, but the process remains incredibly slow. Even today, Pablo Herrera, the biggest hip-hop producer in Cuba, operates out of his apartment.

Because of these technological limitations, Soandry believes that some of the best lyrics in the world are coming out of Cuba right now: “Through speech we have to compensate for the lack of quality that we have musically. We also have to grab the attention of a population that is already a big consumer of salsa and reggaeton. You need to have good lyrics to make people stop dancing and think.”

“Through culture and words you can do more than through politics.”

Soandry’s songs, like much of Cuban hip-hop, are inflected with a social consciousness that comes from a long tradition of Cuban music. One of the earliest forms of popular song in Cuba was Trova, which originated in the late 1800s. Guitarists known as trovadores rambled the country playing songs about social problems and telling real-life stories. “They were a crucial part of the Revolution; they questioned capitalist ideas. As raperos we are also questioning things both inside and out of the island; we are making a new kind of revolution,” Soandry explained.

Though raperos draw on traditional Cuban music, the influence of American gangsta rap on Hip-Hop Cubano is unmistakable—the driving beats, aggressive vocal delivery, and complex rhyme schemes are direct descendants of the American movement. However, it is unwise to perceive Hip-Hop Cubano as simply on offshoot of American rap. While American groups are free to write songs calling for the takedown of the American government and its institutionalized racism, Cuban rappers don’t have the same freedoms of speech.

Cuba consistently rates at the bottom of Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index, and the rappers are not excluded from censorship. The rap group Los Aldeanos was considered “too critical” by Cuba’s authorities and, as a result, were banned from Cuban radio stations. Their albums still can’t be sold in stores on the island.

Other rappers have encountered obstacles because of their lyrics. “There is not a single record label which dares to record us; we depend on clandestine studios,” says Raudel, a rapper from the group Escuadron Patriota. Soandry chose not to comment on the Cuban government’s tight restrictions.

Nevertheless, censorship and limited possibilities for public performance have united the underground hip-hop community. “There used to be an East Coast / West Coast type rivalry between the cities of Alamar and Havana,” Soandry explained. “But, because of the scarcity of opportunity to play our music, everyone comes together.”

Recognizing the power of the music, the Cuban government has also taken steps to encourage and promote rap for some performers. In 2002, authorities created the Cuban Rap Agency and established a state-sponsored record label, Asere Productions. A musician sponsored by the agency is guaranteed the ability to perform, and given access to recording equipment. However, sponsorship comes at a price: state-sponsored raperos must conform to the government’s music standards.

The government’s censorship of social content in the lyrics and the pressure to hybridize Hip-Hop Cubano with traditional Cuban music like Salsa have left a bad taste in the mouths of edgier raperos like Soandry. “We are not political, but we must keep the energy of the streets,” he said.

If not explicitly political, los raperos’ lyrics are certainly polemical. They take on subjects that the government media tries to hide: hunger, racism, class division, and the Cuban youth’s desire to re-organize Cuban society. Soandry is outspoken about these topics, but he rarely approaches them in a straightforward way. He sees racism as a kind of cancer in Cuba society, but he doesn’t simply blame the government or the white population. Instead, he raps about how Afro-Cubans have internalized racism. In his song “Negro Cubano” he raps: “The Black Cuban wants to be white. He is fed Clorox since his childhood. He makes racist jokes about blacks who are in a worse condition than him.”

In his songs Soandry also expresses and celebrates his African identity. “Through culture and words you can do more than through politics,” he added.

“I have a map without a treasure…”

Like many of los raperos, Soandry maintains a degree of Cuban pride while rapping about problems in Cuban society. His song “Tengo” is based on a poem of the same name by Nicolás Guillén, the national poet of Cuba. Guillén’s 1964 “Tengo” extols the virtues of Castro’s Revolution, but Soandry’s adaptation shows a more complex picture. Written during a time when over 30% of the Cuban population was unemployed, the song alternates between pride and frustration for Cuba:

I have a flag and a coat of arms.

I have a map and a palm tree without a treasure.

I have aspirations without having what I need.

The years go by and the situation stays the same.

Despite the sentiment in the last line, Soandry feels hip-hop has brought new hope to the island. When asked how hip-hop has changed Cuba, his eyes lit up before his normally serious face returned. “We have rescued so many young people from the bad life—the hustling life. If you don’t have any direction, you get stuck and wind up on the street,” he said. “Hip-hop helps you to find your own direction.”

The future of hip-hop in Cuba remains uncertain; the government is notoriously tight-lipped about its plans, and, despite constant political coverage on state-sponsored radio and television stations, its citizens are routinely kept in the dark about the policies that will affect their future. President Barack Obama plans to relax restrictions on American travel to Cuba and ease the trade embargo may mean a thaw in relations between the two nations. However with the recent mid-term elections giving control of the House to the Republicans, the fate of these plans remains in doubt. Still, in the past ten years, Cuba has hosted American hip-hop groups like Dead Prez, Black Star, and Common, and recently allowed artists like Soandry to leave the country to perform. This might mean that the government is growing increasingly open to the genre.

Soandry is interested in these tectonic changes, but more focused on how hip-hop can change individuals: “Hip-hop is the best way for people to understand that we have to respect each other. We bring the sounds of a non-violent revolution, new beats of freedom, and the chance to change the way we see each other.”

Read Joshua’s bio

2 Comments on "Soandry del Rio and Hip-Hop Cubano"

I had learned about Soandry Del Rio through Dr. Henry Louis Gates documentary entitled, “Black In Latin America.” I like Sonandry’s rap, entitled “Negro Cubano.” I understand some of the spanish words in the song. Do you have the written lyrics of the song? I would like to get a translation of the lyrics.

Trackbacks for this post