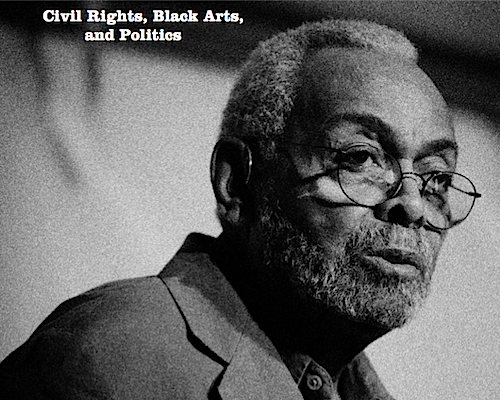

In Memoriam: An Interview with the Late Amiri Baraka

by Sampsonia Way / January 10, 2014 / 4 Comments

On January 9, 2014 Amiri Baraka, poet and activist, passed away at the age of 79. Below is an interview with Amiri Baraka that Sampsonia Way published in 2011, after he came to read with Cave Canem at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh.

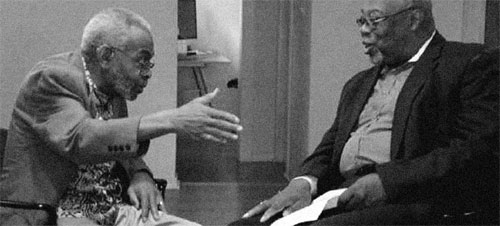

During the Civil Rights Movement these two men were fighting to put an end to the practices of discrimination. While Amiri Baraka did it from New York, Sala Udin did it from Holmes County, Mississippi and Pittsburgh.

Baraka founded the Black Arts Movement, which advocated independent black writing, publishing, and artistic institutions. In 1966 he set up the Spirit House Players, which produced, among other works, two of his plays against police brutality. Then Sala Udin—a man who, among other things, fought for starting Black Studies at the University of Pittsburgh—used to take young people to those performances. Many of these people went back to change their cities, inspired by the work of “the father of the Black Arts Movement,” as Baraka is known.

Almost five decades later, in June 2011, it was Baraka who came to Pittsburgh to read at the poetry event that Cave Canem and City of Asylum/Pittsburgh hosted on the North Side. Sala Udin, a former Pittsburgh City Councilman, sat down with him to discuss politics, the future of black art, and the consequences of making political art in America. Their lively conversation is sprinkled with personal memories, sharp political commentary, and humor.

Because it is a unique opportunity to have two figures of the Civil Rights Movement in the same room to talk about that period and their lives afterward, Sampsonia Way presents this interview unedited and uncut. It is our longest interview to date.

A WAY BACK

Sala Udin: We were just talking about little Ras who’s not so little. I know you must be proud of your son, who is a public school principal, was deputy mayor in Newark, and now has recently been re-elected to City Council. Tell us a little bit about Ras’ entry into the politics of Newark, and how it was an extension of the politics that we started way back.

Amiri Baraka: We used to take my sons to all kind of political things — that included my son Ahi who was very little at the time — and Ras was apparently just drawn to that and picked it up. He and our other son Amiri Jr. were into some political organization when they were in high school.

They organized all the students to walk out of the schools because there was no Black Studies. It was a long journey to where Ras finally got to be the deputy mayor under Sharpe James for four years, for a dollar a year. Now they’re paying deputy mayors $176,000 a year.

Sala Udin: He was a little early.

Amiri Baraka: Well it’s another kind of regime that we have now. But it’s been a long time coming. When Ras went to Howard University some students shut down the school over this Bush appointee who would be on the Board of Trustees at Howard. So the students shut the school down, and I went there and the mayor picked me up. They took me to the school, and the president there was so backwards that he had called a SWAT team.

Sala Udin: He called a SWAT team?

Amiri Baraka: Yes, called SWATs on the students. The students had locked up the administration there. What they did was pull the fire alarm and run out and lock the doors. So he called the SWAT on them. I called people I knew who had children there. I said, “They’re getting ready to do something to your kids.” He backed off after a couple of days.

Sala Udin: That’s similar to the struggle we had at the University of Pittsburgh, where we took over the computer center and locked ourselves into the Cathedral of Learning. At that time computers were as big as refrigerators. We had axes and hammers and were threatening to dismantle the computers, and it changed their tune. They became much more agreeable to having a conversation about Black Studies.

Amiri Baraka: Yeah, I don’t think these students now realize how important it was to do that and that’s why I think that there’s not as tight surveillance by the students and by the faculty over Black Studies. It gets diminished.

What the schools did after all that militancy of enforcing the initiation of Black Studies was to bring in instructors who were not revolutionaries and who were simply faculty members who didn’t care what happened. That’s what’s happening all over the country.

Sala Udin: And the whole initiation is forgotten. They don’t know how they got there. They think that they’re there because of their degrees and their brilliance.

Amiri Baraka: A lot of these Africans they bring in are just intended to be some kind of administrative pawn, but that comes from an era when they thought everything African was militant.

Sala Udin: We go back to a time when we brought a lot of young groups to Newark to see Spirit House [a black community theatre that Baraka set up in Newark in 1966]. Since then you’ve been widely known as the father and founder of the Black Arts Movement…

Amiri Baraka: Remember that we had started organizing people in the Village. We were trying to create some kind of black consciousness because the Civil Rights Movement was unfolding. But when Malcolm X got murdered, a lot of us young writers and painters moved out of the Village and up into Harlem.

I had a play downtown and I was getting some kind of money so we rented a brownstone in Harlem and tore out the bottom floor and set up a theater and then we began to send trucks out into the street: Four trucks every night with music and dance and poetry.

It had a very strong effect on the people because we thought that if we were supposed to be doing such profound artistic things, we needed to bring that right into the neighborhood. What was interesting was the play Dutchman, my play, which won the Obie Award, became a racist play.

Sala Udin: How so?

Amiri Baraka: Well because art in an abstract setting is one thing, but art where you’re actually telling people to do things becomes dangerous. Jean Paul Sartre said that as long as you say that something’s wrong but you don’t know what, that’s art. If you say something’s wrong and you know exactly who’s doing it, that’s political protest.

So we had to work with that and begin to understand that. But we wrote art that was, number one, identifiably Afro-American according to our roots and our history and so forth. Secondly, we made art that was not contained in small venues. We wanted to come out and get into the streets. That’s why I was happy to see rap because here you can hear people running stuff down out in the street. The third thing we wanted was art that would help with the liberation of black people, and we didn’t think just writing a poem was sufficient. That poem had to have some kind of utilitarian use; it should help in liberating us. So that’s what we did. We consciously did that.

We brought artists from all over the area uptown, some of the great musicians of the time. We brought Sun Ra into the community. People were saying Sun Ra’s too out there for the people. But people thought it was dance music, they started dancing to it.

There’s a picture in a book of mine called Digging: The Afro-American Soul of American Classical Music where we’re getting ready to go out into the street, and I’m bringing wine, and at the top of the steps is Sun Ra. It was very effective, and that particular trend spread across the country in Milwaukee, Chicago, Atlanta.

BLACK ART

Sala Udin: How do you see Black Art today?

Amiri Baraka: Well we need to restore its purpose. The thing is you’ve got an Afro-American presidential figure and that disarms a lot of people, even though they still suffer from the same ills. I mean, you see that the Tea Party will pop up.

After the Civil War the slaves thought they were free, but then came the Klan. It’s the same thing. You didn’t need the Klan when slavery was going, but the minute you say you’re no longer a slave then you get the Klan and you get Black Codes.

So you cannot stop struggling just because you’ve got a black guy walking around saying some stuff. Just because his skin is your color don’t mean his brain is the same as yours; if you’re going to bomb Libya you’re nuts. So it’s a continual struggle to raise the level of social consciousness in the country. Not only for black people but for everybody who needs that change.

Sala Udin: Do you still see black artists under the continued influence of Black Art who politicize their art?

Amiri Baraka: Some, but you got a whole wave of people who are influenced by this post-struggle art. People who believe that simply to write a poem about themselves or their family is sufficient. That’s not what it is. It’s the whole question of art.

Everything that Shakespeare wrote was against the rulers in that particular age. In Julius Caesar he wrote about the relationship between government and the people. The Taming of the Shrew was about the oppression of women and Hamlet is about the development of liberalism.

So when you can understand that Shakespeare is dealing with the elimination of the whole aristocratic class in that period you see that all the things he talks about are things that we will have to deal with under capitalism for the rest of our lives. But that’s not the way it’s presented. It’s presented as some kind of extra-realistic mumbo-jumbo in verse that puts people to sleep so they don’t see the essence of what that is. But that’s what artists are supposed to do— help the struggle for the advancement of human knowledge.

Sala Udin: When we came to Newark on many occasions there were several Pittsburgh artists who were influenced by what they learned and experienced at Spirit House. Now they are revered here. I wanted to name them and get you to reflect briefly on their work: Rob Penny, August Wilson, Ed Roberson, and John Edgar Wideman.

Amiri Baraka: Well Rob was actually the most active of our unit. He actually wanted to do the things that we were talking about, use art to advance black life and human consciousness.

August was a poet when we first talked. He didn’t write plays yet; he was a young poet talking to me about poetry and I thought that [his movement into the theater] was a miraculous kind of development. When I first met him, he wanted to know why I wasn’t a Beatnik anymore.

Next thing I know he had become a Muslim and joined the Nation of Islam which he stayed with for about that long [snaps fingers]. I think he and Sonia Sanchez got in the Nation of Islam about the same time and stayed about the same time. Thirty minutes. Then they were doing something else.

I was very proud of Rob and August and how much they did. They came to Newark a couple of times.

Ed Roberson I still know. We worked at the same school. I was teaching, and he had an administrator kind of job, but he was writing poetry, and he still is.

Sala Udin: Wideman spoke of you and Ed Roberson as early influences. He talks about Ed and includes him in some of his anthology work.

Amiri Baraka: Yeah well Ed’s poetry is a very fine, profound kind of poetry and it’s interesting to me. John Edgar Wideman and I have had some discussions—that I really don’t really want to credit as his whole being— on whether or not one should teach icons of Afro-American literature. And my line was “You mean you wouldn’t teach Frederick Douglass? You wouldn’t teach DuBois? I don’t understand.” And then he changed his stance because that’s clearly impossible. If you’re going to teach Black Studies you have to teach the great people.

OBAMA AND THE UPCOMING ELECTIONS

Sala Udin: As we look at the evolution of the political scene up to 2008, you had put forward a compelling argument for progressives that the Barack Obama candidacy represented an opportunity to push forward the agenda for democratic rights and equality. Now more recently you’ve described Obama as a yapping Negro who would take us back to slavery. I wonder what you would say about Barack’s presidency?

Amiri Baraka: The problem is that I have to support Obama because I remember the Republicans. I remember Bush, and I see the ones they have lined up over there now. At the same time he has to be criticized about what he’s done. I have to ask Obama, what are you going to get by bombing Africa? Take the oil away from Gaddafi? Gaddafi as a leader is no worse than others that he’s close friends with. So where is the logic of that?

And Obama has not learned to struggle like I hoped he would. There’s no way to get anything done unless you’re able to struggle with those long-time lobbies. Even when he was first elected we sent 10,000 newspapers out saying “President Obama, no bailout, nationalize the banks, nationalize the auto company.” I had forums to talk about that.

The only way I could justify his actions is that he thought that above all, capitalism–not just petty capitalism, but big time capitalism, monopoly— has to survive for this country to survive.

I still thought it was a respite, but there’s been so many times where he’s been able to do things and then backed off, like that thing with [Henry Louis] “Skip” Gates getting busted. Obama said it was stupid, then he backed off it. They arrested a guy, a Harvard professor, on his own doorstep. That’s stupid. And obviously racist. But to back away from that with some kind of “let’s go drink beer together,” that’s what began to turn me away from him.

I’ve got to support him to the extent I can, but at the same time I’ve got to criticize him.

Sala Udin: What should be the posture of progressives relative to the upcoming election?

Amiri Baraka: Well you know the right is moving towards fascism. This whole business in Arizona, this whole trading unemployment for refusing to tax the rich. In New Jersey it’s the same thing; Governor Christie will not tax the rich, but we have all kinds of budget cuts. That has to be fought, and Obama has to be held as a bulwark against that; otherwise what are we doing?

I think it’s important to fight the fringe, the Tea Party, and understand that a lot of Republicans, and some Democrats, are the Klan in civilian clothes. They just took off the white robes.

Like I said, after the Civil War, then you get the Klan. So after Barack’s election, then you get the Tea Party and it’s the same thing. It’s the Sisyphus Syndrome. You roll the rock, they’re going to roll it back down on your head. Like I said last night, there was a guy named George Romero who predicted the coming of the Tea Party in a film in the sixties called Night of the Living Dead. But the irony about that is a lot of the people are struggling against their own interests, you know, “Keep your hands off my social security.” That’s a federal program. But that’s where we are now, between a rock and a hard place.

During the campaign of the Weimar Republic, the left split up into pieces and permitted the right to grow. While the left was fighting about whether they were Communists or Socialists, Workers, Syndicalists, Hitler was building. So you looked up and suddenly they had blown up the Reichstag—which reminded me of 9/11—and the next thing you know, they had banned the left from the whole parliamentary thing and began to take hostages.

I don’t see the difference between the media, big media, Murdoch Media, Fox, and what the Nazi media was. Everything is to the right, to the right, to the right, and when you see people like [the radio and television host] Glenn Beck for instance, it’s very scary because they don’t represent anything but fascism.

Sala Udin: You called for the formation of a representative assembly, a united front, to organize black politics. How do you see that happening today? There is nothing close to the kind of assembly that we put together with the National Black Political Assembly. How do you see that evolving?

Amiri Baraka: Well it’s going to have to happen again. First of all, the only way we can go forward in this country is that coalition, that united front that elected Obama. Blacks, Latinos, Asians, and progressive whites have to maintain that motion because if that fragments, we’d go backwards. That’s the danger of Obama acting so backwards, because what he’s doing is cutting off his own backers.

I was actually giving money to the campaign in 2008, but I can’t give money to someone who’s going to bomb Africa. You could never back Great Britain and France against Africa or any other powerless people because they’re bloodsuckers. That’s why when you see these movies about vampires and stuff it’s so popular because they’re talking about themselves, they’re talking about the nature of this economy, the nature of this society. They suck blood from defenseless people.

Sala Udin: So rather than building a united front, many of the critics of Obama—especially left critics—don’t do anything as an alternative to their criticism. They exempt themselves from organizing people, and they think it’s sufficient to stand on the sidelines and criticize.

Amiri Baraka: Well it’s like [American author, actor, and civil rights activist] Cornel West. He called Obama a white man in black skin. This guy taught at Harvard and Princeton. I don’t know many black people who teach at Harvard and Princeton. If you got into one of them you’d be lucky.

I was at a Socialist conference and these people were making all these ridiculous statements. I said “I’m a Communist, I want to know where are the Socialists, where are the Communists in this group?” And Cornel says “I’m a Christian.” So I said: “That’s cool,” but I reminded him, “You know why they killed Christ, don’t you? Kicking the money lenders out of the temple.”

Anyway that’s the problem, people feeling that the Black Liberation Movement was a means of getting them into an Ivy League college. The idea that it was to try to change the very nature of the United States is lost on them because they’re perfectly comfortable. That’s why if you look at that book that [Manning] Marable wrote about Malcolm X, the three people pushing the book were Cornel West, Skip Gates, and Michael Eric Dyson.

Unfortunately Marable fell into this kind of thinking or analysis that the “left,” the Democratic Socialists, even the CP today, and the Trotskyites, are more progressive. I said no, the Black Liberation Movement had the most powerful effect on America. Not the CP, not the Democratic Socialists, not the Trotskyites. And Malcolm and all these Black Liberation groups, the Black Panthers, they didn’t want an Obama. But if you don’t understand that, if you’re going to belittle them because they’re not formally Socialist then you don’t even need Lenin.

Lenin said we don’t measure people’s struggle against imperialism by their formal commitment to democracy, but by the effect they have in beating imperialism. If you’re talking about Lenin, don’t talk to me about no left. That’s the problem: You have people who masquerade under some form of social democracy, pretending they’re on the left, but really just dribbling the ball inside regular capitalist America.

A WAY FORWARD

Sala Udin: When you look back at all of the contributions that you have made as a writer, playwright, music critic, and cultural critic, how do you see the peaks and valleys of your own contributions?

Amiri Baraka: Well, I just wrote a play about [W.E.B.] DuBois called The Most Dangerous Man in America. That’s what the FBI called DuBois. But that man was 82 years old and had a cane.

In the play he explains what they have done to him when they indicted him as an agent of a foreign power for talking about peace and condemning the hydrogen and atom bombs. They indicted him as an agent of a foreign power at 82 years old. He explained that once that happened, publishers that sought his writing no longer did that. They began to stop his speaking engagements. He said “I was a man that every Negro in the United States wanted at one time.”

He became a pariah. So I could understand that. I said yeah that’s what they will do. If you do something that the powers don’t like, they make you invisible. That was the first case against McCarthyism, and at the end, even though DuBois had Vito Marcantonio as his attorney, the last Communist in the Congress. But when he had won, he said: “Now the little children will no longer see my name.”

You can write what you want to, and say what you think needs to be said, but in the end they’ll hit you back.

Sala Udin: Have they done that to you?

Amiri Baraka: Oh yeah, even just money-wise. Last year I lost $16,000 in terms of speaking and stuff. I went to Princeton, and they said: “It’s going to be hard for us to have you at Princeton because we have to spend an extra $10,000 on security,” like people are going to come and shoot me. But it’s a normal thing if you understand what you are doing and who you are opposing.

People are always coming up to me, “Didn’t you have a play on Broadway?” Why should I have a play on Broadway? I mean you think that people want somebody to come up to them and say “You need to die,” and then they say, “Let’s put this on Broadway.” It’s a choice you have to make, it’s a choice you make and you have to live with it.

Sala Udin: What projects are you working on now?

Amiri Baraka: Well the play on Dubois I just finished two weeks ago. That took up my time for the last few months. I’ve got a book called Revolutionary Art that I’ve been waiting on for two years from Third World Press; I don’t know what the publisher’s doing. He sent me two sets of proofs, I marked both of them and still no book.

We are also doing things in Newark: we have a project called Lincoln Park Coast Cultural District. That’s an old district in Newark where the abolitionists lived and used to preach against slavery. Right next to that was the black music center, so we’ve sort of annexed that area and we’re building houses down there. For the last five years we’ve had big music festivals. Matter of fact it’s coming up again next month, and we’re organizing a tribute to James Moody who’s a Newark musician.

Tomorrow [June 26] we’re having a celebration for Juneteenth, the day when word that slavery was over reached Texas three years after the fact. It should be interesting.

We’re just trying to do things now to support Ras and his struggle because he’s the most progressive person on that city council. He’s always involved and struggling against these backwards forces. Politics for some people is nothing but a gig. It’s not about advancing anything in the consciousness.

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka, born in 1934, in Newark, New Jersey, is the author of over 40 books of essays, poems, drama, and music history and criticism. He is a poet icon and revolutionary political activist who has recited poetry and lectured on cultural and political issues extensively in the USA, the Caribbean, Africa, and Europe.

With influences on his work ranging from musicians such as Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, and Sun Ra, to the Cuban Revolution, Malcolm X and world revolutionary movements, Baraka is renowned as the founder of the Black Arts Movement in Harlem in the 1960s. Though short-lived, it was a movement that became the virtual blueprint for a new set of American theater aesthetics. The movement and his published and performance work, such as the signature study on African-American music, Blues People (1963) and the play Dutchman (1963), practically seeded “the cultural corollary to black nationalism” of that revolutionary American milieu.

Sala Udin

Sala Udin, whose legal name is Samuel Wesley Howze, is a former Pittsburgh City Councilman, where he represented the 6th district.

Udin traveled south with the Freedom Riders, and during the 1960s, worked primarily in Holmes County, Mississippi, for the benefit of the Civil Rights Movement. It was there that Udin rallied for school desegregation, farmer cooperatives, and voter registration. Upon returning to Pittsburgh, Udin helped to establish a branch of the Congress of African People.

Udin is also known for his acting in the play Jitney and the friendship he had with the famous author of the play August Wilson.

4 Comments on "In Memoriam: An Interview with the Late Amiri Baraka"

Trackbacks for this post