The Sky Over Havana by Jorge Alberto Aguiar Díaz (JAAD)

by Sampsonia Way / August 23, 2013 / No comments

Translated by Zach Tackett

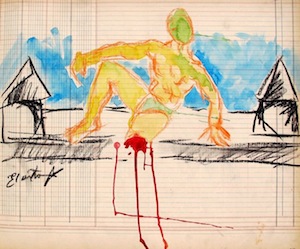

Painting by El Sexto.

—I’m dying, damn it, and you’re going to die alone on this shitty island! —she shouted at him.

Then she hit him. Violently. It split open his lips and nose. It left him collapsed against the wall.

—Tell me, faggot, why don’t you hit me back?

She spat on him. He became still. Looked up. Then he saw the sea. Dawn.

She talked about her money. He wanted to go down to the reefs. Get his feet wet, wash off the blood. She talked about the honeymoon in Japan, about the permanent visa to the United States, about dual citizenship, about her rich and powerful family in Venezuela. He wanted to get his feet wet. To sleep. Maybe even sleep under the water, in another world.

A policeman walked up the sidewalk across the street. He stood waiting. She saw him.

—What if I were to say that you were hurting me? What do you think about that? What can happen to you for conning and taking advantage of a tourist?

- Jorge Alberto Aguiar Díaz (JAAD)

- Fiction writer, poet, literary instructor. In 2002 he published in Havana his short-fiction volume Adiós a las Almas in Letras Cubanas editorial house. His opinion columns appear in Cubanet. He is the webmaster of the blogs Fogonero Emergente and Cuarto de Máquinas/Compasión por Cuba. He was the chief editor of the independent literary and opinion digital magazine Cacharro(s).

- He is residing temporarily in Spain, as a Tibetan Buddhist monk.

- Read More…

He also saw the policeman. A second. He looked at the sea again. What would happen then? A starving Cuban and a tourist from the First World. Who would believe him? And when the police asked why she attacked? What could he say? The real answer was so unlikely that it would get him locked up in a prison cell. He leaned against the wall. In the distance he heard a ship announcing its entry into the bay. The policeman remained on the sidewalk. She attacked me because she wants me to marry her and go back to her country, he would answer. “And I do not want to,” he thought. Everyone was going to taunt him, the police and his friends, when they heard. His wife and his mistress, of course, they wouldn’t believe anything.

—Tell me. What if I call the police?

He did not answer. He was breathing anxiously and with some difficulty. I forgive you, Ana Marina, he thought. He recalled her naked, moaning with pleasure. Always laughing. He recalled her long, beautiful, black hair. He turned his face to see her one last time. Stunning and pallid. With her hair swept up under a scarf.

—It’s all the same to me —he said—. If you want to, kill me. I am free, Ana Marina, free.

Before closing his eyes, he heard a seagull in the distance and smiled.

He woke up. Once again the view of the sea from his window in that little room in Malecón. A piece of sea and a window. He had nothing else. A dirty mattress, a typewriter, a few pesos to buy rum and get drunk. He thought of Ana Marina. She would arrive from London at noon at the latest. But at least he was going to eat well for a week. He also needed to get out of this slum filled with prostitutes and criminals.

He looked at the blank page. Not a word. To write is to destroy oneself. He stood up. He had to forget his hopes of being a writer. He looked down the avenue—still deserted at dawn. He yawned. Hunger. Tiredness. Ennui. The entire early morning to write at least one page. No novel, no money, and no hope. What could he do? Wait. But wait for what? Nothing. Only wait. Waiting is enough. He thought of Ricky, of Kimani, of El Bolo. His friends were determined. That night they would launch into the sea on a raft. Such an irony. Some arriving by plane in first class and others escaping in rustic rafts.

- The Writer Speaks

- JAAD about JAAD

- “Writing should be for me a rebellion against my own conformism and hypocrisy. To be a dog. No to believing in “literature.” No to denying others when I affirm myself. To be anti-dialectical. No to living in resentment. Neither gangrenous memory nor predictions as in a fair. To make the tea and then leave. JAAD, which does not exist, returning.

-

”

A shout threw him out of his tired state. It was the neighbor. Once again fighting with her husband. Every day, the man arrived from the street at this hour and beat her. A mulatto ex-convict who made her whore for a dollar at the corner of Monte and Cienfuegos. Why not write those stories that he saw every day? Why not write about his rafting friends? Why not write about Ana Marina?

He took out the letters he had sent to her in the last six months. He wanted to reread them. Something was wrong. He never spoke of leaving the country. She, however, had phoned him three days before to say: I’ll come get you. We will get married, and I will get you out of Cuba in less than a month. I love you.

He looked at the letters. He recalled her naked. He remembered her beautiful, long hair. He thought he would like to make love to her in the middle of the city, behind the wall of the Malecón, on the reefs. But this marriage and escape puzzled him. What about his wife? And his lover?

He opened a letter. He began to read. In the distance, he heard the siren of a ship.

They had met on Obispo Street. She had gone to a bookstore looking for the books of Carpentier, Lezama, and Reinaldo Arenas. They had discussed literature. They had talked about their lives. No timidity, no hypocrisy, no repression, no guilt. They had liked each other at first sight. An hour later they were thinking that they had known each other all their lives. She got too drunk and he loved her voluptuous body, her hair, her way of speaking, her age. “I go crazy for both young and mature women,” he confessed. She had turned forty-five, ten years his senior. He spoke then of his wife who was nearly fifty and his lover of eighteen. The flower and the fruit of life.

Ana Marina invited him to a bottle of rum. She lived every moment as if it was her last. “You are a person sick of words and I am sick of life,” she said walking down Obispo, searching for the sea and Plaza de Armas.

The dealers offered them everything. Cigars, inexpensive luxurious food, rum, aphrodisiacs. Anywhere you could go, a huge black man showed up, selling any good, suggesting women, grabbing his own balls. They walked slowly, seeing everything and talking about what we always talk about: Government, human rights, the difficulties of traveling abroad, poverty, hunger, child prostitution.

The heat made them both sweat and her nipples were visible through her shirt. She put her hand under her shirt to dry them and he wanted to bite her there, like an animal, and pounce on top of her. Ana Marina’s eyes looked with longing, discovered an untamed instinct. “I would like to dry off your sweat,” he said as they sat in the park. “And I would like you to dry me off,” she said.

That night was spent in the small room in Malecón. They endured the heat, the bad smell and the filth of the overflowing toilet in the middle of the slum’s hallway, the shouts and fights of neighbors over a lack of water. He opened the windows and entered her forcefully. He grabbed her by the waist, bit her back and they looked out at the sea. In the distance, they heard a seagull and a ship announcing its arrival to Havana.

Painting by El Sexto.

The policeman crossed the street.

She was crying and questioning herself. Life is the great shit. Why do we live like we live? The worst fear is not of death but of life.

He was also crying. He had spoken of his freedom. He had spoken of writing, of self-destruction, of the love for his wife and his lover.

—Well, aren’t you just a tropical playboy! You piece of shit! How can you love two women, huh? Egotist. You only love yourself.

The police stopped again five or six meters away. She had her back turned.

—Why the fuck did you promise to marry me? Why the fuck did I come to this island of shit? Narcissist! Fucking playboy!

She wanted to hit him again. She understood it was useless. He looked like a mangy dog leaning against the wall, swallowing blood and his fear of living.

—You’re not worth anything. You have wasted the opportunity of a lifetime. Stupid. Failure. You will never even amount to a mediocre writer.

And that’s how she went. She barely watched the traffic to cross the street. The cop walked away smiling.

He was alone. He listened to the waves. It was daylight.

Ana Marina, Havana is a village. And since you left, Havana is like a ghost town. I think of you every day. No exaggeration. If we had not met in that bookstore, we would be missing something. Something that we would need. You are real and you’re a ghost. All I have left is language. And the language names the impossible, an absence that time reconstructs in our imagination in order to escape death. So, my words condemn me to live in the solitude of my own loneliness. Enclosed in this tiny room, I look at the sea. I live paying rent that I can no longer afford, but I need to be alone. I want to write. I can not live without writing. I see my wife and my girlfriend two or three times a week, sometimes they are tolerant of my loneliness. If they did not exist, I wouldn’t think twice about marrying you. Since you left, you are the ghost; the smell of these sheets materializes in infinite desire, in pleasure that is already pain and forgetfulness. You live in love because you are pure instinct. A force that destroys to create. I am adrift in this adrift city. I do not want to live if it is not to write and be with both of those two women, with those women who I need so much and who resembled happiness. And here you come. I am afraid. Sometimes I think I’ll die before I’m forty. Is this possible? I need time. I’m lost inside myself.

He put the letter aside. Ana Marina was about to arrive at any moment. Six months later she is returning. Six months later he is still there, living in the same disgusting manor, sitting with his head in his hands, waiting. Waiting for what? Just waiting. Waiting —period.

He looked at the sea. He saved all of the letters. They all said the same. The same ideas in different words. He thought of his friends. He thought of his lover and his wife.

They left the Plaza de Armas and walked again toward Obispo. She invited him to her hotel. He said no and told her of his little room. They spent the last two days touring the city and always ended in that cavern. Three hours before her departure they were still there. What could they do? Say goodbye.

She would return a second time. He wrote a poem for her. A breeze entered through the window and cooled the heat. They had lived a shameless freedom without any consequences, they had unleashed their ghosts. They lived all the fantasies they ever wanted to live. To feel the impulse of death behind every minute. To transfigure life into something that is not a thing, a simplification of the absurd, a stultifying routine, a connection to the Machine, he wrote to her.

I like your poem. And I like your hair. Would you like to leave Cuba? Yes, but not to stay. Why? I have to write. You are so strange. Yes, and I’m crazy and all you want, but I have to write. Sentenced to write in this light that blinds me. Do you feel free? Sure, after all, one day you discover that freedom is hidden in your head. Is freedom for you to be with two women at the same time? Why do you ask that? Don’t you think you’re falling into a cliché? Forgive me, it’s that I was jealous. Jealous? Yes, jealous. You’re falling in love. It is possible, and I know it will be hard to forget you. You will forget me. No. Yes. I’ll never forget you. Neither will I.

—Y-you going w-with us or are you st-st-staying? Ricky asked.

—Let’s go, man, this place is shit. There is no future here, said El Bolo.

Kimani did not speak. Kimani always spoke very little. One night he said it all, and then never spoke of the matter again: We have to get out. Cuba is not a real place. Cuba does not exist.

They were in the door of his slum. Everything was ready. The raft, canned meat, medicines, compass. Everything.

—I have to stay. Maybe in a year or two …

—Are you crazy, man! You said that two years ago.

—Are y-you sc-scared?

He did not answer. So many questions to answer!

He checked his watch. Ana Marina was coming. His friends planned their death and he was there waiting. A corpse that sees how the others will die.

—K-Kimani, s-say something.

Kimani was going to say something, but he stifled himself. Suddenly, the wife of the ex-convict fell into a ball in the hallway of the house. The black man came up behind her and hit her right there with a hose. He gave two or three kicks and left her unconscious.

Some neighbors intervened. The guy came out of the lot, crossed the street and sat on the wall of the Malecón.

—Let’s go guys—Kimani said.

Five minutes after his friends were gone, a Panataxi arrived and Ana Marina stepped out. He saw her from the window. Then he looked up. He stared at the horizon.

Finally he went down to the reefs. He wiped off the blood. The water was cold. She was right. He was an idiot. He would never be even a mediocre writer. His wife was about to leave him. She knew about his lover and eventually she would break up with him. The young one, with her mere eighteen years, needed life, and he was vegetating.

Painting by El Sexto.

The future had become an idea. A single idea. Stay and wait. So just wait. He sat on a rock. He dipped his feet. Freedom could be inside one’s head, but he put his head under water anyway. To live in another world. To be a seagull, the whistle of a ship.

He thought of his friends. When he could not hold his breath any longer, he flung his head out. He inhaled the breeze. It was beginning to get hot. He heard the noises of the city.

She got out of the Panataxi. Two guys, one giant white man and one black man with huge gold chains, approached her to offer her something. Everything a foreigner needs to be happy in the largest of the Antilles. She looked at the window. She looked at the gate. She saw an old man sleeping in a doorway, some children came to her asking for candy, two children who went tourist hunting from early on.

She closed the door of the taxi. She paid. Gave him a tip.

She entered smiling at the slum. Where is my great writer? Where is my tropical man? She stopped at the door. The wife of the ex-convict had recovered and came out with a knife in hand looking for the husband. An old woman, indifferent to everything that had happened, threw stew at her pig and corn at her chickens.

The toilet was overflowing. Someone had the record player blaring. And in another room, someone was listening to a speech by Fidel on the radio. Ana Marina smiled. She knocked on the door a second time.

Ana Marina, as Virgilio Piñera said, one day you will see that I was right to stay and live in my country. Logic and a sense of history. What else do you need to know? The sense of history can be the sense of a country but also, and above all it should be, the sense of a human being. It is possible to love two women. Even three. True love is not possession. Cuba does not exist. The world does not exist. My rebellion is pointless. Nor live domesticated. Should I end in suicide? No. I wait. What do I wait for? Nothing. Only wait.

He stopped writing. He left the paper on the table. She would read it after she arrived from the airport. He sat down to wait for his friends. They would come to confirm their trip for that night.

He prayed that they would not see Ana Marina arrive. “Fairy Godmother” as Kimani called her when he told Kimani that she was daddy’s little girl and that she had a lot of money and lived in London.

But she will not pay attention to those words. Language is death itself. She would live a week with him. They would make love again with the same passion and freedom. In a hotel, in the small room of the slum, near the reefs. One week. Enough time for a decision.

—Everything is decided. I told you that I do not want to leave.

—Do not tell me that. You have a week to make up your mind.

—Everything is decided.

—No, please. I’ll come to get you. I’m dying.

—We are all dying.

—I’m dying —she would say.

And she will undress. He’ll be on his back watching the sea and will not see her nakedness until she calls him, tells him, “look at me,” and then will turn slowly to look at her. And he will look at her.

—I’m dying —she will say a second time.

He will see an unknown body. A black spot, a breast amputated. And he will understand. Understand why she took off her clothes, why she came with her long, beautiful black hair tied in a handkerchief. Why it is no longer black nor long nor beautiful, of the cancer that progresses, that eats her voluptuous body, of chemotherapy, of the pain.

—Let’s live together for what I have left.

—Ana Marina, we are lost among such fear and such loneliness.

He would watch the sea. Like a corpse that sees the death of the entire universe.

—I love you.

—I love you too, but it can not be.

Kimani is alone at open sea. He closes his eyes. He doesn’t want to see so much darkness all around him.

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.

Leer en español.

__________