“Living My Life Naturally Was Considered a ‘Crime'”

by Dissident Blog text by Payam Feili / April 2, 2015 / No comments

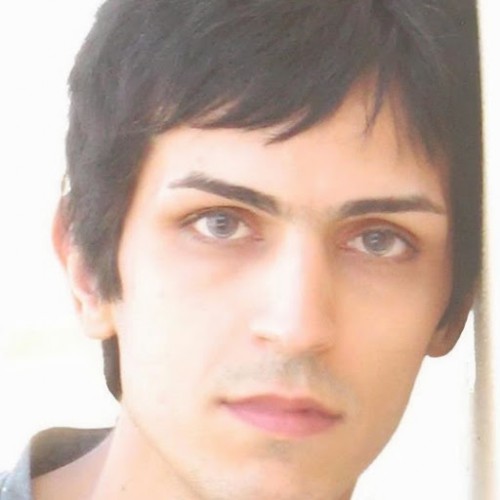

Being gay in Iran has a very high price. Especially if you are a writer and open about your sexuality. The 21-year-old Payam Feili was the first writer in Iran who openly wrote about his sexual orientation, in a number of works which he has been unable to publish in Iran. When the Iranian regime published his picture under the headline “faggot,” threats against him forced him to leave the country. Here he tells his story.

It was not easy to live in Iran. I was a member of a minority group for which the Iranian Government, along with a significant segment of society, did not officially recognize basic and natural rights. Living my life naturally was considered a “crime” and people’s perspective of my life was one of perversity and corruption. Iran’s judicial system treats homosexuality as a crime and there is a prejudice that ensures harsh punishments to the criminal. The religious sector, which plays an important role in Iranian society, has a bitter perspective on homosexuality and, therefore, society also does not welcome those who are different from them. The authorities constantly treat this minority, of which I am a member, with contempt and intimidation and instead of using the word “homosexual”, they use “same-sex player.” This is the extent to which the Islamic Republic does not want to hear anything about minority rights, and instead speaks of their compulsion.

I also had another crime. I was a writer and in my stories I spoke as much about my identity as I knew. Through writing I would discover myself even more. But, this “me” was also a homosexual and speaking and writing on this topic was illegal. It was only outside of Iran that my books had the possibility of being published, which would perhaps come with consequences. My first and only book, which was allowed to be published in Iran, never received the permit for a reprint. In addition, publishers in Iran failed to acquire the necessary print and publishing permits from the Ministry of Islamic Guidance for a few collections of poems and stories I had ready for print. Being a homosexual affected many things in my life. I was not afforded the same natural flow of life as others, such as the rate at which my career should have progressed. My close friends avoided socializing with me and I was excommunicated. I saw that I had to pay a heavy price for my sexual orientation, while my family also paid their share of this price with their basic right for peace and security hampered.

I lost my job as an editor at a publishing company due to numerous visits by plain-clothed security officers at my workplace. Meanwhile, a newspaper linked to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, in an article titled “A Creeping Flow of Content Production for Same-Sex Players in Iran”, declared that I was supported by “anti-Iranian” mass media outlets and produced “inhumane and further development of same-sex play” content under the orders of opposition agents. In yet another article I was accused of participating in an Israeli-supported movement intent on causing disorder in the system. A few months before leaving Iran I had a dialogue with a Hebrew-language newspaper and in that interview I announced that a Hebrew copy of one of my novels would be published in Israel in 2015. This revelation was used by the newspaper linked to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards to connect me to an “anti-Iranian movement in Israel”, which in legal terms carried dire consequences for me. A few days after the publishing of my counter-claim to the newspaper I departed Iran. Now, away from turmoil and threat, I have time to reflect on my life in Iran. How could they say that my identity – which I did not want to conceal – led me to such crisis and exile? For all of the years that I was working in Iran I knew that the other parts of my books were not important to the Ministry of Islamic Guidance. The important thing was my name, which had made it to the banned list at the Ministry of Islamic Guidance. My books were no longer permitted to be published in Iran and I was not permitted to be the honest voice of my own life.

Iranian society does not demonstrate flexibility and does not reconcile with the nature of sexual minorities; they don’t know them. The authorities filter liberal media and propagate phobia. Everywhere life is against you. Because you’re a homosexual, you must constantly prove your innocence in the handling of all your other relationships. I had to prove to society that I was not “lewd” or a “slut” and I had to prove to my family that I have no intention of marring their trust. I had to prove to the Government that I exist and I had to prove to the authorities that the punishment for a love outside their understanding is not execution… that love has no punishment. Society is afraid of you. They will reject and be cruel to you. Undoubtedly, this is a corrosive life. In Iran, discrimination against sexual minorities take place with “legal” and customary backing, and the most common avenue is escape and isolation, which perhaps is not without danger. Maybe I was fortunate, through my self-isolation and writing, to have given my life a shape and to have not allowed my loneliness to lead me to passivity. But, many, who are caught up by “being a homosexual in Iran”, lose this opportunity. When I look back at the years spent in Iran, more than anything else, it was the danger of “hiding” and turning to a “secret life” that threatened me. The same dangers that also threaten the lives of millions of other people in Iran.

This piece was originally published by Dissident Blog on December 16, 2014.