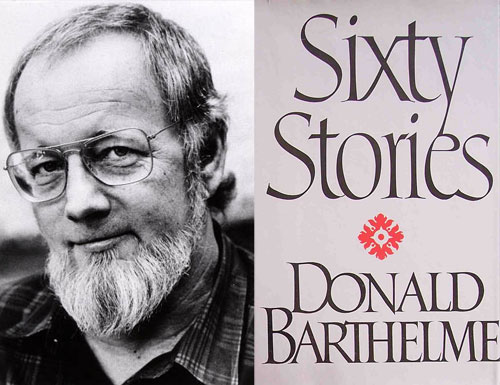

Donald Barthelme and I

by Yaghoub Yadali and translated by Parvaneh Torkamani / March 7, 2014 / No comments

On discovering a new writer in Iran, and rediscovering him in Pennsylvania.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons and Chris Drumm via Flickr.

“Some of us had been threatening our friend Colby for a long time, because of the way he had been behaving. And now he’d gone too far, so we decided to hang him.”

- “Enemy…terrorism…nuclear bomb…war.” These words are often used by American media to describe Iran. The image the media presents is often hazy, incomplete, and distorted. The political and military aspects of my country are covered mainly in a negative light.

- In Under Eastern Eyes (I have adopted the name from the novel Under Western Eyes by Joseph Conrad), I will write about those topics which American media either cannot or does not want to talk about. The emphasis will be on social and cultural aspects of Iran although, out of necessity, I will talk about politics, despite my despair.

- Yaghoub Yadali, born in 1970, is a writer and television director. His first work of fiction, the short-story collection Sketches in the Garden, was published in 1997. It was followed in 2001 by Probability of Merriment and Mooning, which was named book of the year by the Writers and Critics Award. His first novel, The Rituals of Restlessness, won the 2004 Golshiri Foundation Award for the best novel of the year and was named as one of the ten best novels of the decade by the Press Critics Award. He has also published many articles and reviews of literature and cinema in newspapers and magazines in Iran.

This is the first sentence of a story by Donald Barthelme. It was published in Persian about twenty-one years ago in Gardoon, one of the intellectual magazines for youth that was being produced at the time. For the young people like me, who were thirsty for another glimpse at the world of stories, it was a significant event. Discovering a new writer, both in terms of technique and form, and also in terms of theme and content, was revelatory. Thus, for a while, this story was what my friends and I talked about—we, a few struggling larrikins who loved movies and stories. I remember a friend of mine had the whole story memorized, and we all knew several sentences by heart. Every once in a while one of us would do something the others didn’t like and we’d say: “Colby, you have gone too far!”

When postmodernism became popular in Iran, we twenty-somethings would consume whatever postmodern text we could get our hands on. In literary discussion groups we’d show off our knowledge by speaking the mouth-filling names of western schools and writers to the older generation, who were not interested in such texts. Back then, in our innocence, we didn’t understand that our sources were incomplete and, at best, second-hand.

I am not sure, but at that time most of the works of Barthelme had not been translated into Persian. Those that had been were scattered and rare. In our youthful enthusiasm we dutifully searched for any clue about Barthelme, but it didn’t work out well. We didn’t find much in Persian and none of us were involved in learning English. We had so many unread Persian books, and university classes, and jobs, and marginal entanglements that there was no time left for learning English. And even if we knew English, we didn’t have access to books and stories by Barthelme. When we were students, there was no public internet and our libraries had a very poor selection of Latin sources and literature.

About ten or eleven years ago, when there was time, and I learned English, and had access to the internet, I found and read Barthelme’s original stories. Then I felt the excitement and enthusiasm of being a student again—especially since I had taken up an experimental path of writing and was interested in new forms and structures of the short story. Back then, stories like: “The First Thing the Baby Did Wrong,” “Glass Mountain,” “I Wrote a Letter,” and “The Death of Edward Lear” were interesting and exciting to read.

I translated to satisfy my heart, and my first experiences in translating from English to Persian were quite an education. I found out that when you decide to translate a story, you become whole-heartedly involved in the world of the author. You gain a deeper understanding than you would by reading the piece.

For example, the form of the story “Glass Mountain,” which is written in a hundred segments, attracted my attention almost entirely. Following that, I decided to practice by writing a story in several episodes, each consisting of one sentence. Of course, like most imitated work, the piece was not successful.

While I was entranced by his short stories, I never read long works by Barthelme. Even now I don’t have an enthusiasm for reading them, but a little while ago, I came across a short story by him on a Persian site, and all my memories with Barthelme from the past twenty years came back to me, walking in front of my eyes like a collage or postmodern movie compressed into a few seconds! I soon started to reread his stories. More than anything, I wanted to know if I would get excited by reading Barthelme again.

The result was interesting: Barthelme is still Barthelme for me! Likable and enjoyable, even though I don’t learn much form his stories anymore—rather, that some of them have lost the appeal they once had—in all, I must say his short stories are respectable and admirable. I wrote these lines in acknowledgment of a writer who has had a significant role in the emergence and formation of my literary eye. It’s intriguing that only when I came to Pittsburgh and took residence here, did I remember that Barthelme was born in Pennsylvania as well, and that his eighty fourth birthday is next month.

Happy birthday Mr. Barthelme. If you hadn’t written your short stories the world of literature would certainly be lacking.