The Complicated Risk: An Interview with Pedro X. Molina

by Nicole Arthur / June 11, 2020 / Comments Off on The Complicated Risk: An Interview with Pedro X. Molina

The magnificent and ever-enthralling political cartoonist Pedro X. Molina is currently an artist in residence at Ithaca City of Asylum and a visiting international scholar in the Ithaca College Honors Program. As an international cartoonist, his work has been featured in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Courier International. He has received numerous awards, including the Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award from Cartoonists Rights Network, the Excellence in Journalism award from the Inter American Press Association, and the Maria Moors Cabot Award from Columbia Journalism School. (See some of his most recent work below.)

The magnificent and ever-enthralling political cartoonist Pedro X. Molina is currently an artist in residence at Ithaca City of Asylum and a visiting international scholar in the Ithaca College Honors Program. As an international cartoonist, his work has been featured in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, and Courier International. He has received numerous awards, including the Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award from Cartoonists Rights Network, the Excellence in Journalism award from the Inter American Press Association, and the Maria Moors Cabot Award from Columbia Journalism School. (See some of his most recent work below.)

In 2018, Molina’s home country, Nicaragua, erupted in protests when the Ortega-Murillo regime instituted a number of repressive policies, including pension cuts and raised taxes. After dozens of protesters were murdered by the government and paramilitary groups, President Daniel Ortega declared public protest illegal. As protests became more prevalent, so did the violence of the regime’s response. Since April of 2018, hundreds have been killed and thousands injured in demonstrations. Last December–not long before Christmas and nearly a year to the day after fleeing Nicaragua, Pedro X. Molina made time to speak with Sampsonia Way about his exile and the power of humor in the midst of oppression.

Journey Into Exile

To start, would you mind telling me a little about the journey from Nicaragua to where you are now?

When the crisis in Nicaragua exploded and many protests began taking place all around the country and in my city, I was working as a cartoonist for the digital newspaper, Confidencial. And as the protests grew, I began to cover the demonstrations as a journalist, too. The protests were very civic and led mostly by students, but I witnessed firsthand a very quick and violent response from the government. The very first protest that I covered in my city ended with a gunman from the government party shooting in the air. So, it was very clear from the very beginning that they were going to respond with violence against the people.

Two or three days later, we already had four or five people killed in protests all over the country. In a couple of weeks, we had 20. Three days into all this, a journalist, Ángel Gahona, was killed by a single bullet to his head, which was broadcast to the world, as he was transmitting live from his Facebook stream. So, again, it was pretty obvious from the very beginning that the government was looking toward violence as a solution.

When did you notice the situation beginning to affect your vocation in the media in particular?

In the weeks following, things just got worse and worse, especially for members of the independent media. Many independent journalists were beaten up by fanatic groups or the paramilitaries of the government or even the police. They were beaten up, they were robbed, they were arrested, and things just got worse and worse and worse.

As weeks turned into months, the number of political prisoners rose into the hundreds, and to this day, there are still many people who are missing. We just don’t know what happened to them.

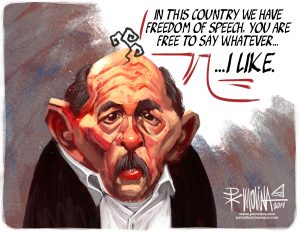

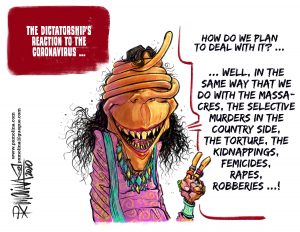

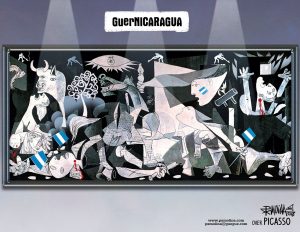

Cartoon by Pedro X. Molina

When did you begin considering leaving Nicaragua?

A few months after the crisis began people started to leave the country by thousands, going into Costa Rica, Panama, Spain or to the United States as the main alternatives. It was a very difficult situation. Last December 13th marked a year since the police came into the offices of Confidencial, where I published my work. They came in the middle of the night and took away everything — computer equipment, recording cameras, whatever they could get their hands on. They took it all. In the morning, all of my colleagues came into the building to find that they didn’t have any equipment.

But they started borrowing equipment from friends and others who were able to help, and within the day we began working again. And then again, by the end of the day, the police forces of the regime came back. Always in the middle of the night. Only this time they took possession of the entire building. So as we are speaking right now, they are still in possession of the building.

It’s very serious, because aside from publishing the daily digital newspaper, we also produced two televised news shows, which had to be discontinued. At first, even though we lost our building, we tried to keep the shows going by asking another independent media publisher with multiple stations to help us to air the work. But by the following week, that became untenable. Exactly a week after Confidencial’s offices were shuttered, the regime went into the offices of 100 % Noticias, one of the very few independent TV news stations, and did the same thing to them, shutting them down. But this time, two employees, Miguel Mora and Lucía Pineda, were still inside the building. So they took them and charged them with something like promotion of terrorism. They ended up putting them in jail for more than six months. Nobody was able to see them during that time, aside from their families. They were kept isolated. The reason they were finally able to get out of jail was because of international pressure for the release of political prisoners, which, at the time, was about 700 people. And so, because of international pressure, the political prisoners were freed after about six months. But they are still being harassed and our TV stations are still occupied by the government. Ultimately, the state’s continued takeover of all independent media created so much intimidation that we moved these programs online–where they continue today.

So this happened in late December 2018. Afterwards, a lot of journalists started to go into exile, because it was very clear around this time that there was nothing these people would not do to frighten and repress government criticism. So I knew and many of my colleagues in Confidencial knew that we needed to get out. I am a member of several international cartoonist organizations. These organizations, as well as other journalism organizations were monitoring my case. All of them agreed at that point that it was better for me to leave than to stay, and that they could offer more support to me if I left. I took my family with me, and I left on December 25, Christmas Day. After I left, there were many more journalists who had to leave through blind spots on the border to Costa Rica.

Humor as Resistance

Going back to the beginning of your career, when did you first begin making art and how did you begin to integrate justice and commentary into your work?

Well, I was raised in the 80s during the Cold War. The US and Soviet Union were, essentially, using Nicaragua as a playground for their political interests. This led to a civil war. There was a Sandinista government who had an army, and there was the irregular army who had the support of the Reagan administration. The Reagan administration eventually imposed a full trade embargo on Nicaragua in an effort to take down the Sandinistas.

So, as a little kid growing up during an economic embargo, I wasn’t exposed to the things kids commonly have at that age, like superhero comics and cartoons for example. We had only one TV channel and it was owned by the state. So, I was always looking for things to entertain myself. The only things I could get my hands on at that time were humor comics from South America, Mexico, and Cuba. That’s what I started to read when I was like six or seven years old and that developed my love for humor and drawing.

Cartoon by Pedro X. Molina

I used to read humor comics like Mafalda from Quino, Argentina, which is a very popular comic strip in Latin America. It was about a gang of kids pretty much like Peanuts, but with a lot of social commentary embedded in it. So from the very beginning, what I would call humor, was humor but with critique.

As I grew older, I discovered cartoons from newspapers and that was a natural evolution for me. The war ended in the 90s. I was just finishing high school, I had to find something to do, so I went to study graphic design. But I actually spent most of my time in the library, reading newspapers from outside Nicaragua, like The Washington Post, Time Magazine, Newsweek, or The Economist. I was around 17 when I started trying to get my cartoons published. I was 19 when I got my first gig as a staff cartoonist for a national newspaper in Nicaragua. Since then, I’ve always been doing cartoons, always from a creative point of view, a political view, or a critical view. I wanted to talk about the war I was living in and how I was understanding it. And something emerged — it was the idea that I was able to use something that I love — drawing, art, comedy — to express and process the world I was living in. And I have been doing it for more than 20 years now.

Your art includes a number of different expressions: cartoons, comics, illustrations. Some of your work is quite serious in tone, but a fair amount has a comedic edge. What role do you think humor plays in political engagement?

I think humor is one of the best weapons that we have when we are dealing with oppressors — when dealing with the kind of people who see themselves as the Messiah, you know? Because humor helps you to bring them back down to a human level, to bring them down to earth. You can put them in a situation where you are making fun of them, so you are humanizing them when they see themselves as something superior and even divine. And when you see them as human, then you see that they can be defeated. It’s a very, very powerful weapon.

In Nicaragua, every day you will see fear in people. Somebody could just kill you in the middle of the street during a protest, or they could take you out of your home in the middle of the night. Terrorists are at times running around in pickups with AK 47s, and their heads covered to intimidate. So there can be this huge feeling of fear all around the country. But people are starting to use humor, especially in social media, to try and help them deal with the situation. A year ago, a lot of people in the general population were drawing their own cartoons, trying to make jokes about these people. It helps them to beat their fears, which is amazing.

Even in protest, you will see how people will use humor. For example, by December of last year, hundreds and hundreds of people had been killed by the paramilitaries in the streets, so people were very afraid to go out in the streets and protest. There was one thing people did: they took white and blue balloons, the colors of the national flag, and they blew them up and released the balloons on the streets of cities in the middle of the night or very early in the morning. So, early in the day, you could see these squads of paramilitary people, you know, very heavy guys with military clothing with their head coverings and the AK 47s, struggling to step on all of the balloons. There is a defiant humor in a scene like that. It was a way for people to stand up and to show the ridiculousness of everything. And it was very, very, very good for the people. But every time they tighten their control and the violence grows, it gets harder to find something to laugh at.

Cartoon by Pedro X. Molina

So then does humor ever reach its limits for you?

Because of the ongoing situation in Nicaragua, from April of last year to now, my cartoons have turned more serious. They are more akin to graphic narratives of what is happening in Nicaragua and not so much about humor itself. I have been working with humor in cartoons for many, many years. But my first concern is always to connect with the people, with what the people are feeling. I remember a while ago, there was a family living in Managua, and the paramilitaries of the government wanted to go into the family’s house and use their roof as a vantage point from which to shoot people on the street. The family denied them entrance, and in response to this, the paramilitary set their whole house on fire, killing everybody in it. They ended up killing six people, including two babies. I remember that day. When you have to do a cartoon on a day such as that, you can’t use humor with that level of tragedy. I went in a different direction, so that I could connect with the feelings of outrage or sadness that people were feeling at the time. Most of my cartoons since April are more concerned about that — about feeling that connection with the people. It can be done with humor, but it doesn’t have to be that way all the time.

What do you make of the tension between humor and political correctness? Have you felt limits imposed on your creativity because of it?

Oh yeah, of course. Political correctness can actually pose a real problem for humor — not only cartoonists, but everyone working in humor. It has been that way for the last 10 years and is growing. I absolutely think that there are many things that need to be corrected in the way that we used to be. I mean, looking back on humor in the 60s or 70s, you can’t deny that there were simply a lot of things that we just shouldn’t be doing right now. We must evolve in this way and continue to perceive the times in which we are living. But political correctness can also be used as an excuse for intolerant groups of power to impose an agenda and try to avoid criticism. Many leaders try to shield themselves behind the excuse of political correctness to avoid criticism. It’s a very complicated subject. Nothing is the same. There is no rule of thumb that you can apply to everything.

These are very challenging times for people who work with humor. I will say that our biggest danger as we discuss and think about these things is fanaticism of any kind. There is not a single movement, social movement, or human movement that will not be in danger of falling into fanaticism. So we have to be careful, because when people become fanatics, the first thing they lose is a sense of logic and a sense of humor. As a cartoonist, I want people to understand that there is nothing so sacred that it cannot be criticized when it needs to be.

Cartoon by Pedro X. Molina

The Risk to Create

You’ve spent so much of your career advocating for justice and global freedom of expression. And you’ve just painted a picture of the risk to create firsthand. I have to ask, in the face of such blatant danger, did you ever consider stopping? Not creating critical art anymore?

Yes, it has been a temptation several times in my life. Not only because of the serious situation going on in Nicaragua. I used to get hate mail all the time. The kind of threats that I received were quite intense. This past year, I received messages threatening my family as well. Sometimes you think, Oh my God, is this worth it? Is this something that is worth doing? And sometimes when you are doing these cartoons and you are trying to make people think — they just don’t get your cartoon or they get it wrong. And you say, What’s the point of doing this? Especially when the few people who really get it are drowned out into the noise. Of course, you think, Well what am I doing? Throughout my life, I have asked myself this question. And the only answer I can give is: this is what I can offer; this is what I can offer to the people of Nicaragua.

Because of the dictatorship, we don’t have strong opposition parties or political leaders in my country. So a strange thing began to happen: people started to follow priests and independent journalists. We began to be seen as moral leaders, which, of course, is not our role. We are only journalists doing our jobs. But when a lot of institutions are missing in a society, you can find yourself in a role that you were not aiming to be in. You start having a different form of responsibility. And I ask myself, Why keep doing this? It is because the best thing I can offer is what I can do with my cartoons and my commentary and my criticism. That’s what I do as a citizen. What can I offer as a human being to this world. I can offer my discontent. I can offer my humor. I can offer my particular way of expressing myself through art. So that’s what I do. It’s very simple. If I wasn’t doing this, I don’t know what else I could be doing. And if I withhold, if I stop, I will still suffer. I will still be frustrated. Only that then I will not have any way of expressing it. So it’s actually very simple. It fills a need of expressing yourself because otherwise you will only get more miserable and miserable and miserable until you die. It’s a complicated risk.

Do you feel that others understand how complicated the risk is?

Yes, sometimes. I had to go into exile to keep doing this work. It’s difficult because those who were left behind, who couldn’t leave for whatever reason, sometimes feel that in my leaving they’ve been betrayed or abandoned somehow. This hurts, but I do think that if hearing these kinds of comments about me is the price that I have to pay in order to offer the best that I have to offer, which is my work, then I have to pay it. And that’s it. I could have stayed in Nicaragua and at some point they would have taken me and put me in jail and I would no longer be able to create. I was not willing to accept this, so to preserve my creative power, I had to leave. This is both good and painful.

You mentioned that the office building where you worked for Confidencial in Nicaragua is still occupied by the government one year later. How do you assess the current climate in Nicaragua as it relates to freedom in the media?

Sadly, the situation of free press in my country continues to grow worse. Last December, when I left, there were still traditional media outlets in existence. Now, one of the second biggest newspapers in Nicaragua, where I was previously a cartoonist, no longer exists. The government put an embargo on all the material needed to actually print newspapers, so people don’t have access to paper or ink or anything from the outside. The newspapers whose spaces have not yet been occupied are dying out because they don’t have the resources to keep producing. Others are printing on half sheets of paper or half the number of pages, and others have had to lay off a lot of people just to survive.

And as for TV stations, most of the major stations are owned by the Ortega-Murillo family, which as you know, are husband and wife, president and vice president. So you don’t have a lot of places to inform yourself with the truth. This family power, Ortega and Murillo, with the money they got from the oil deal with Venezuela… they bought a lot of things, among them, most of the biggest TV stations in the country. They gave each station to one of their kids, even the one that was supposed to be a national TV station of the state. It doesn’t matter to them because for them, family and state are the same thing; family and government are the same thing. As a result, there are not a lot of places where people have access to independent, free press. A lot of us in exile are still working from different countries and trying to put together everything for Confidencial. A few weeks ago, our director, who was in exile in Costa Rica, decided to go back to Nicaragua to see if he could get the government to give us back the building, but it hasn’t worked.

Throughout it all, what I’m really proud of is not only about me, but the independent media journalists of my country. Despite everything that has been going on, we have been able to produce our stuff nonstop throughout the entire year. I have been able to do my daily cartoons every day without interruption. For this, I am proud and thankful. It’s not the ideal situation to be working in, but at least we are working.

Cartoon by Pedro X. Molina

James Baldwin, who was a black writer during the Civil Rights Movement, said, “I love America more than any other country in the world. And exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” This quote has always struck me because to bind criticism with love especially for someone in Baldwin’s situation, feels so unexpected or even countercultural. It seems like in your work, you, like Baldwin, not only criticize Nicaragua, but demonstrate a clear love for your country. Can you speak to what you love about your country? What’s been the hardest thing to leave behind?

I think the sense of family has been so hard to leave behind. Not only my actual family, but the feeling that you belong to a place. That you are helping to build a place that you can call your own. And I am not talking about a home or house or anything. I’m talking about a society. I do miss that. And I like to think that I am still working alongside other Nicaraguans who are trying to achieve a better Nicaragua with more freedom, with liberty, with equality, with free elections. I like to think that I am still working in and for that society.

But being out of your place, it’s emotionally difficult. I do think that you can use it to fuel your work. Even that disconnection can give you a different perspective on things. I really, really like this quote by Baldwin because that’s the way I feel about many, many things. If I love Nicaragua, I must criticize Nicaragua — Nicaragua, as a society, as a government — because I care about it. But take religion, for instance. I am Catholic and for many years I was very famous in Nicaragua for being critical of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in my country. A lot of people and Bishops really hated me because of this critique, but because I care so much for the church, I believe I need to continue to examine and identify any wrong in it. It’s my duty as a believer.

No healthy patriotism comes from the notion that the things you love are above critique. Where there is injustice, oppression, flawed systems within your society, country, government, religion, or family — we must speak out. Otherwise, things that are bad, they tend to get worse. You can prevent that through your work, your commentary. You have to try. You will not achieve it by yourself, but with enough people, it becomes easier to tell the truth.

Nicole Arthur is a Sampsonia Way staff writer based in Ithaca, New York.