Ambient Buzz: An Interview with Urayoán Noel

by Sampsonia Way Staff / July 24, 2019 / Comments Off on Ambient Buzz: An Interview with Urayoán Noel

Photo by Luis Carle

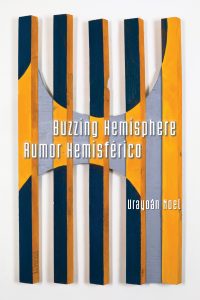

Urayoán Noel’s most recent poetry collection Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico (2015) has been described by Victor Hernández Cruz as “a stereo ping-pong game between two languages [Spanish and English].” The book features a variety of bilingual and translingual effects and a spectrum of compositional methods and technologies. Attentive to the personal and the political, it celebrates poetry’s fluidity and multiplicity in the era of global capital.

Born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico and now living in the Bronx, Urayoán Noel is the author of several books of poetry and of the critical study In Visible Movement: Nuyorican Poetry from the Sixties to Slam (2014). He is also a performer and translator, most recently of Pablo de Rokha Architecture of Dispersed Life: Selected Poetry (2018). He is Associate Professor of English, Spanish, and Portuguese at New York University.

In April 2019 students enrolled in Piotr Gwiazda’s graduate course “Contemporary Poetry and the Question of Being Together” at the University of Pittsburgh corresponded with Noel about the aims of his writing and how he positions himself in the process of composition. The following questions were posed by Christopher Fink, Joseph Jang, Rhea Crone, Joshua Corson, LT, and Willie Kinard.

In “Alphabet City / Ciudad Alfabeto” to what degree does the placement of the text on the page shape the interaction between the two languages? What does the abyss of whitespace — in its varying capacities — affect the work and the readers’ perception of the contrast between the two languages? Does the writing ever fully engage with the space it takes up in the book, in the same way that words must engage with silence when they are spoken?

In conceiving BH/RH I was reading and thinking about poetics from across the Americas that played somehow with whitespace and meaning/silence: Haroldo de Campos’s Galáxias (1984), Pedro Pietri’s Invisible Poetry (1977/1979), Josefina Báez’s Comrade, Bliss ain’t playing (2008), and others. There is a whole riff in the book, of course, on the side-by-side pages as hemispheres but also on the limits of the page, on the vertiginous gap between whitespace and text, English and Spanish, original and translation (etc.), a gap I have no desire to bridge. That gap is also the one between text and body, which I signal in performance through the noise of my phone and its apps. Since many poems were composed on or with the aid of a smartphone, the vertiginous aspect of poetry is also in this case about the pitfalls and randomness of transcription, the violence and seduction of translation.

Throughout Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico you use rhyme with incredible touch and effect. Considering that there’s a concept in the book that it is not necessarily a work of translation, how did this alter your process of creating rhymes? There are often similarities in the rhyme, but there are also moments when the rhymes are divergent, as in “Deshoraciones / Sentiences” and “Solneto / Sunnet.” Did you approach one language first? Did you write the passages simultaneously?

I don’t know that the book is not translation. It is not equivalent translation, to be sure, but all translation is non-equivalent. In the case of pieces such as “Solneto / Sunnet” I was trying to transcreate the form, so that rhyme becomes a constraint, closer to OuLiPo certainly than to how formalist poetry tends to be understood in the U.S. In many cases, I approached one language first, though I made it a point to not always place the two versions in the order they were written. In other cases, the two versions emerged in tandem, as part of a process of translingual embodiment and improvisation.

Public spaces in your book seem to simultaneously hail and alienate the speaker and subjects of various poems. I’m thinking specifically about “Mi Hemisferio Ardiente / My Burning Hemisphere” for two reasons: 1) I find it personally resonant, since I am currently preparing to go to the hospital myself; 2) it presents a central concept — “hemispheres” — as not strictly spatial, but as bodily/embodied; more specifically, embodied in/by a body that is (or was recently) malfunctioning, and therefore placed in the (semi-)public space of a hospital. Why embody hemispheres in this way — i.e., why situate them in a body, in the first place; and why do so in a body that was/is hospitalized? And, to play with language a bit (a kind of play the book seems to invite) why emphasize the act of staring out of the hospital window to and across a body of water?

The reference in that poem is autobiographical. I was indeed in the hospital overlooking the East River, and so the hemispheric and the littoral/lit-oral were enmeshed, as they are so often in my book (I’m an island person, after all, so water is never far). Embodying the notion of a hemispheric Americas was my way of engaging and maybe countering its imperial history, from the Monroe Doctrine on down. From the perspective of disability studies (a field I’m increasingly invested in), I like the idea of thinking of the buzzing in my brain hemispheres not as a malfunction or impairment but as a “buzz” that suggests both something amiss electrically and a trippy, altered state that we might all share.

In “Voice Creaks” the speaker says, “I’m 15 minutes / away from Georgia / and light years away / from nowhere / and yes I know / I’m sentimental / my only antidote / against the monu/mental.” In a poem that is “orally improvised,” a form that one could argue resists the “monumental” itself, it seems important that both memory and the retelling of memory be controlled by the speaker. So, if sentimentality (i.e. subjective memory) is the “antidote” to the “poison” or the “monu/mental” (i.e. the state-sanctioned memory), how does technology, both the phone and book, intercede/facilitate/subvert/adhere to the battle for memory and voice?

Well, the phone gives an illusion of control: the digital screening of the world that promises a “digital baroque” (Timothy Murray) plenitude but confronts us with temporal folds. The print text is a transcription of that “oral improvisation,” and one that takes transcreative liberties in engaging the space of the page (“monu/mental”), so I am less interested in the organicity of that original body that walked and improvised, than in the remediations that reembody the text in the reader. Of course, the reader’s perception is also shaped by their own memory-archive of poetic/performative texts, their own pattern recognition of how this piece might (or not) gibe align with other modes of lyric/performative walking (Josefina Báez, Wordsworth, Neruda, whatever).

“Pastoral” returns us via its title to a poetic imagery we have recently seen emerge across various readings and in a variety of new contextualizations. Here it is “between urchin / and eros / a border being.” Yet, it does not seem to me that the temporal takes the position of primacy in this poem. Diaspora seems at once to be an issue at hand in the land, automation, and in the voice. In time, however, it seems underscored, or perhaps unsettled. Does this unsettling elevate the shifting of the poem’s space from stanza to stanza?

It’s hard for me to decouple space from time, especially as someone who left Puerto Rico over 20 years ago and returns now with the sense of inhabiting another space and another time. That title is of course somewhat ironic: though the poem was improvised on a beautiful beach (the one closest to my heart, where I learned to swim), the larger backdrop of that poem is the in the ravages of neoliberal austerity, the gutting of the Puerto Rican archipelago that began years before Hurricane María, even the postmemory of 1898 (“a new 1898,” as Pedro Pietri says). The poem’s stanzas are then provisional, the extensions of a breath exercise that leads back to a body aware of its precarity and seeking an equivalent to the troped pastorals of old-school poetry within the mild buzz/voz of scatting into a phone, becoming one with the crashing waves, letting a littoral/lit-oral promise (is it Atlantic? diasporic? diasporous?) linger.

“Variaciones Sobre un Paisaje de Violeta López Suria / Variations on a Landscape by Violeta López Suria” makes a brief reference to Orpheus, thought of as the creator of poetry in Greek mythology. Why include Orpheus, a player of the lyre and muse, in a poem that is not inherently lyrical? What does this say of grief or the relationship the speaker has to truth, grief, and mourning?

I’m not sure, but you’ll have to ask López Suria, as I believe that reference came from her poetry, as alluded to in the notes. It’s true that Orpheus might seem out of place there, but I’m really drawn to the eccentric classicism of López Suria’s work; there is something decidedly unmonumental in her poetry, a minor-key lyricism that often feels subversive for that reason. I’m not sure what you mean by “inherently lyrical,” as the main part of that poem (the part I composed) is in fact a kind-of-love-poem (maybe an Ashberian love poem?), referencing a then-looming breakup. López Suria’s lo-key lyricism (wise, self-aware, aiming for beauty yet eschewing the uppercase Muse) felt true to both my own head/mindspace at the time and to the spirit of a book that wants to center voz without bracketing off the ambient buzz that constitutes us.