The Mosul Music Teacher Fighting Extremists with Strength of Strings

by Nawzat Shamdin translated by Ubab / August 24, 2016 / No comments

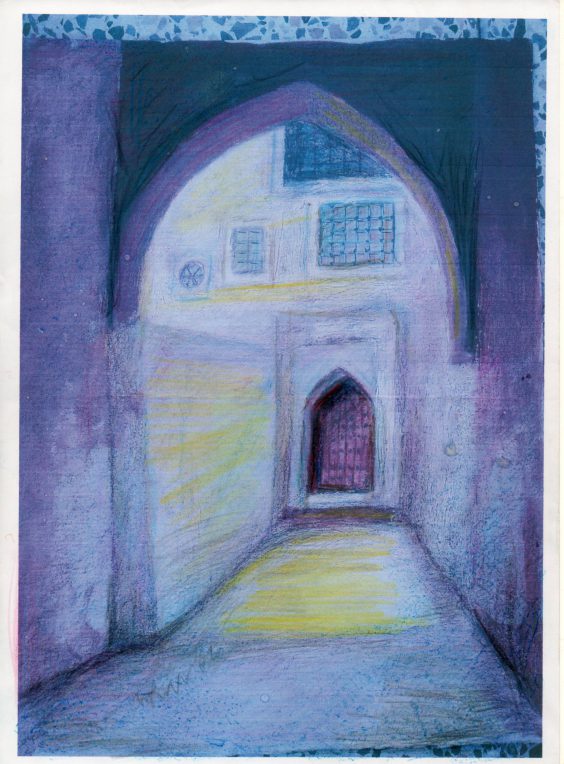

Visual by Hazem Atraqchi. Image provided by the author. Rights reserved.

As darkness falls and there are fewer Islamic State fighters on the streets of Mosul, a young man makes his way cautiously through the old alleyways of the old city. The northern Iraqi town has been under the control of the Islamic State, or IS, group for over 18 months now. The young man walks slowly, cautiously, as though he was in disguise. When he feels more secure, he allows his legs to run. But as he runs he continues to scan the doorways and corners, to make sure nobody is watching him sprint.

- Nawzat Shamdin is a prominent Iraqi Kurdish journalist, novelist, and literary critic. Throughout his journalistic career, he has worked for publications such as Ninevah Daily, the dailies Wadi Al-Rafidayn, the Mustakbal al Iraqi, and the Bagdad-based daily Al Mada. He has served as the editor-in-chief for the cultural journal Thaqafat since 2010. His novel Half A Moon was published in Arabic in 2002. He is a member of the Iraqi Union of Writers, the International Press Union and the Iraqi Journalist Association. He also has a law degree and is a member of the Iraqi Bar Association. Since 2004 Nawzat has been threatened by opposition groups linked to al-Qaida and coalition forces. He has been living in exile in Skien, Norway since 2014.

Then he reaches his destination. He knocks on the door three times. The door opens. And Ahmed, the young man, feels a secret thrill, the pleasure of breaking the extremists’ draconian rules.

Asad Aziz is waiting behind the door. Before Ahmed arrives and knocks in the way they arranged, Aziz has been fretful. He watches the road from his garden as it gets dark. He mutters to himself, trying to work out how long it will take the young man to get to the door. “He just left his house,” Aziz says to himself. “Now he’s going around the corner. Now he’s in that neighborhood, then passing through this one, he’s cleverly circumnavigating checkpoints and taking back alleys. He should be here any minute,” Aziz thinks out loud.

In fact, the two men are accustomed to this routine. It happens almost every evening. Once Ahmed has arrived, the two men walk across a courtyard to what appears to be a pile of rubbish, unneeded, unwanted household goods. The men both brush aside old cartons, boxes of dirty clothing and rags and bring out two black bags. They open these and take out their ouds, the stringed Middle Eastern instrument that spawned the Western lute.

Isn’t it stupid to prevent somebody from playing an oud when parrots commit sacrilege in sixty different octaves?

Then, having made their way to a nearby basement, they take a seat opposite one another. The light of a single lantern shines on their faces showing their smiles, their fingers gently balancing on the musical instruments which have resisted, like true revolutionaries, the harsh punishments meted out by the extremists who consider most music ungodly. The IS group’s laws against music means that anyone found playing it or even listening to it will be penalized by whipping, or at the very worst, by being thrown from the tallest building in Mosul.

But music has been Aziz’s world for a long time. His oud is a weapon to resist his city’s occupation, a city where he has grown old. His sons left for Erbil, in the comparative safety of Iraqi Kurdistan, within the first month of the occupation of the city, in the summer of 2014. But Aziz, who is single, refused. And each evening he meets with Ahmed, his student.

The pair meets in a basement which has had its windows blocked by bricks and cement. Iraqis in Mosul have used their basements for many things, to escape the summer heat or hide from falling bombs. Aziz and Ahmed use this basement to escape censorship.

For Aziz this is a battle, part of an internal war that began for him when the first black banner was raised over Mosul roofs, when the extremists declared that he was living in an Islamic state, a state he has never recognized.

“They started their reign here by waging war against art, prohibiting it in all its forms,” Aziz says. “They destroyed a statue of Mosul’s most famous musician, Mullah Othman al-Musili, that had been there for many years.”

They closed all of the music schools and recording studios and said that nobody could listen to music in cafes, at home or in their cars. While the IS group has predetermined punishments for anybody caught smoking or stealing or spying or committing adultery, there are no set penalties for playing music. The judges appointed by the IS group to interpret Sharia, or religious, law decide how many lashes a musician or listener-to-music should get.

Aziz recalls four cases, where musicians and a music store owner as well as teenager who was listening to music, were whipped in various locations around Mosul for their infidelity to God. Then there was another case where a young man was actually beheaded for listening to music; his case led to the arrest of five other young men. Nothing has been heard from these youths since they were arrested.

But, as Aziz says, the extremists cannot stop nature’s music. “Why don’t they fight the bulbuls?” he exclaims. “Why don’t they try and stop the wind and the thunder and the trees and water from playing their music? Isn’t it stupid to prevent somebody from playing an oud when parrots commit sacrilege in sixty different octaves?”

Aziz tells Ahmed to spread the fingers of his right hand. Therein lies the secret, he tells his pupil tonight. “The extremists thought that they could make music extinct by destroying musical instruments and punishing musicians,” Aziz explains. “But what they did not realize,” he nods, as he prepares to play his oud, “was that our real weapons are our fingers.”