From Delhi By Heart

by Raza Rumi / April 20, 2016 / No comments

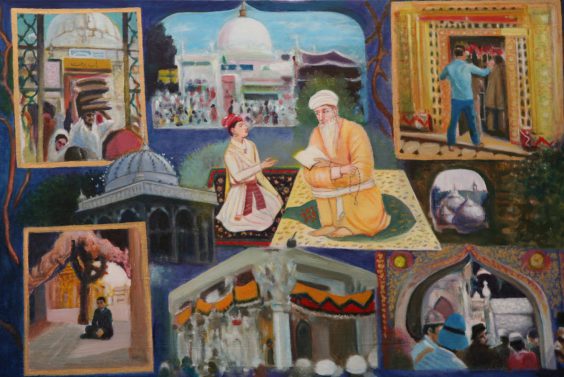

Image by Raza Rumi. Used with permission.

I am not sure how I met Bunty. It was perhaps through a reference from the office during one of my early work-related visits. Bunty Singh, brother of Sunny Singh and Goldie Singh, became my guide and companion through Delhi. Sunny and Bunty have set up a mini empire of rental cars through investments made by Goldie, who lives in Germany and is married to a “good” German girl. Bunty, a boisterous, internet-savvy young Sardar, found me to be somewhat like him. We spoke in Punjabi, often using lines that would quite miss those outside the “Punju” realm. And we both were equally fascinated by each other–the thirty-something grandchildren of Partition.

So after an hour of awkward client-service interaction, Bunty decided to befriend me. It was just the right thing to have happened I guess. How else would I know a real Sardar? Most of my Sikh interactions took place as a student in the UK decades ago.

- Raza Rumi

- Raza Rumi is a policy analyst, journalist, and author from Pakistan. For a decade, his work has appeared in The Friday Times, Pakistan’s foremost liberal weekly paper. He has also been a commentator for publications that include Foreign Policy, The Huffington Post, The New York Times, Al Jazeera, and CNN. As a leading voice against extremism and human rights violations in Pakistan, he has faced surveillance and attempts on his life. In 2014, he survived an assassination attempt led by a militia linked to the Taliban. He sought refuge in the United States, where he has been a fellow at the New American Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). He is the current ICORN writer-in-residence of the Ithaca City of Asylum in the United States.

However, as soon as there was mention of Partition, there was a palpable unease. It was only after a day or two that he confided how half his family was butchered at a railway station. To use Amrita’s words:

Who can guess

How difficult it is

To nurse barbarity in one’s belly

To consume the body and burn the bones?

I am the fruit of that season

When the berries of Independence came into blossom.

(Translated by Harbans Singh)

Bunty’s stories were a classic mixture of family oral histories and textbooks. The textbook narratives were humanized by real accounts of co-existence. But the confusion remained. For instance, when the familiarity deepened, he would talk of “Muslims” who cut up Sikhs and Hindus near Aimanabad, now in Pakistan. Yet these tensions were not enough for him to resent me as an individual. I too shared my narrative of Sikh brutality and also mentioned various characters and incidents from the Urdu stories of Manto. He was bewildered. The loss of humanity even in a fable can be unnerving. Bunty wants to hate me but cannot. He does not take money from me at the airport a few days later. Perhaps he finds in me the humanized phantom of the “other.”

Bunty accompanies me to the Purana Qila that I have seen from the outside, time and again, as I pass by on the busy Mathura Road. It is exceptionally quiet, except for a few students with their books and an odd couple or two seeking intimacy in its not-so-dark corners. This is the landmark of ancient Delhi. The Mahabharata tells us that Indraprastha, Delhi’s ancient name, meaning the “abode of the king of the gods,” was the great capital city which the five Pandava brothers created on the banks of the river Jamuna. The veracity of such a claim is disputed. Archaeological excavations show that there was indeed a township here but what sort of a settlement it was is not known. Fifteenth century BCE, I tell Bunty, and he stares at me in disbelief.

Quintessential to the Delhi experience, this site mixes time and memory. From 1450 BCE to the present day, the monument tells various stories. The standing walls that we see today are most likely the work of the unfortunate Emperor Humayun who chose this as a residence in Delhi and added many structures to the ruins. Proximity to the Jamuna must have played its part—in hot Hindustan, water and breeze were essential for survival.

The large fortified city of Purana Qila was symbolically named “Din Panah” and by 1538, much of the work was completed. However, the rise of Sher Shah Suri halted the process. Sher Shah Suri took over Delhi and ousted the feeble Humayun (known for his proclivity for opium and indecision). Sher Shah added a lot here—a stunning mosque and the octagonal Sher Mandal. Of course Din Panah became Dilli Sher Shahi. Sher Shah’s reign, brief as it was and not of the Mughal ilk, has not been closely studied. The construction of the Grand Trunk Road that is shared by India and Pakistan is attributed to him. However, most notably, Sher Shah was a secular Pathan who was a true forerunner of Akbar in that he believed that religious freedoms and a discrimination-free regime were essential for effective governance.

In 1555, Humayun regained control of Delhi and he returned to his Din Panah. In a year’s time, he tumbled down the stairs of Sher Mandal with books in his hand, thereby ending his tumbling life. Not far away from this place lies his magnificent tomb reflecting the grandeur of Gur-e-Amir of Tamarlane in Samarkand. He was succeeded by the greatest of emperors, Akbar. Little did Humayun know that three centuries later, his descendent, Bahadur Shah Zafar, would escape from the Red Fort to take a boat down the Jamuna and reach Purana Qila to go to Hazrat Nizamuddin’s shrine. Also, Humayun would have never imagined as he was dying, that the last Mughal emperor would be captured by the British at his tomb.

Bunty tells me in chaste Punjabi, “Aais jaga tay badi history haygee! (Too much history in this place!)” We walk around a huge well and cross the royal baths until we find a little tea stall. Bunty is amused with my ramblings. He is also interested in the Sikh shrines in Pakistan. These are well looked after, I reassure him and inquire why his family has not yet visited Pakistan.

Continue reading this excerpt on page 2