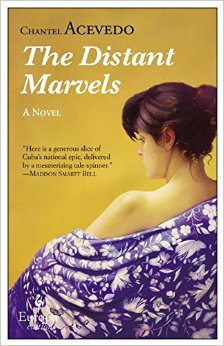

Excerpt: The Distant Marvels by Chantel Acevedo

by Chantel Acevedo / May 4, 2015 / No comments

Chantel Acevedo is the author of Love and Ghost Letters and A Falling Star, respective winners of the Latino International Book Award and the Doris Bakwin Award. As Assistant Professor of English at Auburn University, she founded the Auburn Writers Conference and edits the Southern Humanities Review.

The following is an excerpt from her most recent novel, The Distant Marvels. Chantel is one of the writers appearing at the 2015 PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature, running from May 4 to May 10. Read more work by participating writers in the 2015 World Voices Festival Anthology.

_______

This Cuban woman, so beautiful, so heroic, so selfless, a flower to be loved, a star to gaze upon, a shield to endure.

– José Martí

Prologue

An unexpected envelope was delivered to me two months ago, on the first day of August. The outer package displayed the address of the University of Havana, Department of History in blue ink and a symmetrical print. My name was written in a different hand, and my address in yet another, as if the package had passed from person to person, each contributing some element to its outward appearance. Unnerved by all of those invisible hands, I left the package untouched all afternoon. But I could feel its presence, like fingers reaching into my purse, or trying to lift my skirt slowly. Accustomed to being alone, the package began to feel like an intrusion, and I could no longer stand it.

So, I opened it. Inside there was a pair of letters. The first, new and crisp, the blue ink rubbing off on my fingers, explained the second, which was old and crumbling. María Sirena, it began, casually, impertinently, as if I were an old friend, we believe this letter belongs to you. It has been housed in our archives, unopened, for many decades.

The letter, it was explained, was waylaid somehow at the turn of the century, had turned up in a collection of war-era correspondences sold at auction, and acquired by an alumnus of the university. An ingenious student, they wrote, had tracked me down as part of his thesis. And on it went, describing the historical effort to preserve what was most important, and find homes for the insignificant.

I worked the brittle flap open, chips of paper falling like confetti. I pulled out an article from an American newspaper, so fragile that tiny parts of the paper crumbled to dust, etching out words and individual letters, as if the thing were censoring itself before my eyes. Another page, this one made of onion-skin, upon which a Spanish translation of the article had been written in delicate, old-fashioned penmanship, held my attention for a moment until a small square of stiff paper fluttered to the floor from within the envelope.

I bent down and saw that it was a picture of my little boy. My hands, holding the envelope and pages, curled into question marks, and then all of the contents of the package, those unwanted, insignificant things to the historians at the university, slipped to the floor.

That day, I sat on the floor and read the article again and again. I put the picture in my bra, close to my skin, until a corner of it bent, then, I wept for that small damage. I could not undo the crease, but I found a frame for the picture, one deep enough to house the article and translation with it. I whispered the diminutive of his name, the only name I ever spoke to him, “Mayito,” and wondered at the way the envelope had found its way to Maisí, and my little cottage by the sea.