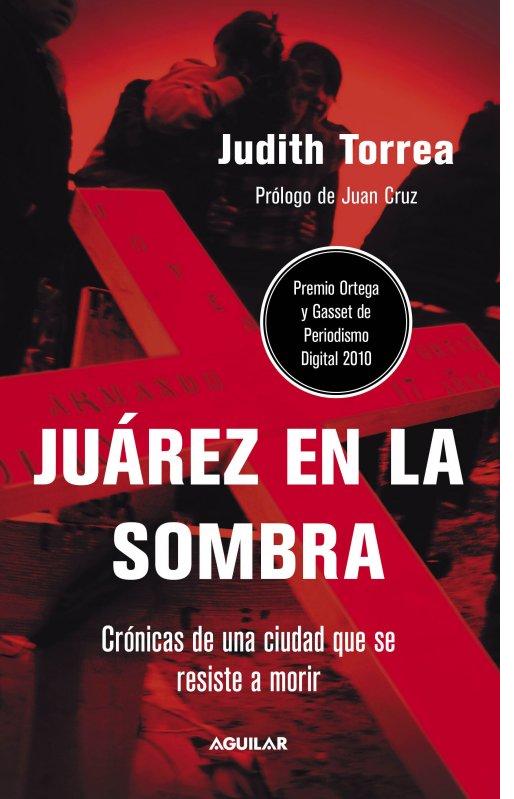

Excerpt: Juárez in Shadows: Chronicle of a City that Refuses to Die by Judith Torrea

by Judith Torrea / April 13, 2015 / No comments

Judith Torrea is a Spanish journalist living in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, a city devastated by battles between drug cartels and the “war” President Felipe Calderon declared against them in 2008. Torrea covers drug trafficking, femicide, and immigration, while living in one of the most violent places in the world: between 6 and 27 people are killed in Ciudad Juárez each day. She has won several international journalism awards for her work, and her blog, “Juárez en la Sombra del Narcotráfico (Juárez Under the Shadow of Drug Trafficking),” won the 2011 Best of Blogs Award in the Reporters Without Borders category. In Sampsonia Way’s 2011 profile on Torrea, she said, “My blog came out of a need to tell the victims’ stories without censorship, because in Juárez there is no freedom of speech.”

Here is an excerpt from Torrea’s book, Juárez in Shadows: Chronicle of a City that Refuses to Die.

_______

Introduction

NEW YORK TO JUÁREZ

New York glamour at the party: cocaine and high-fashion. It’s nighttime. During the day, my computer screen shows the number of dead in Juárez. An email lets me know about a murder: another person who told me their story and is no no longer with us.

Looking down between the skyscrapers from my office window, I make out the people on their way to work. They’ll ride up in elevators without so much as a hello to their traveling companions, as they reach the heights of this city of dreams that are so often shattered.

Yesterday, I couldn’t take it anymore. After drinks at some socialite’s mansion, I was invited to dinner at one of Manhattan’s most elegant restaurants. Table for six: French cuisine, wine. Couples impeccably dressed at this posh spot. Dead expressions on faces flattened by a surgical aesthetic.

The conversation: fundraising at a benefit gala for a museum… Weekends in the Hamptons and the upcoming presentation for a new diamond collection.

I listen until the New York millionaire seated to my left asks me where I went on vacation.

“Mexico. The border. Juárez,” I say. “I love it there. Though it’s not the same now. President Felipe Calderon’s so-called war on narco trafficking is taking place right in the middle of a turf war between the cartels to control the drug routes from Colombia to their American customers.”

“Judith! Judith!” he says, interrupting me. “Let’s not talk about such serious things! Let’s toast to Mexico!”

“Have you ever considered how many dead (Juárez residents) it takes for you to (peacefully) consume a gram of cocaine?” I ask.

Silence. Utter silence.

Every time I returned to New York – I’d been going to Juárez every two months – it got harder for me to come back to my life as an entertainment reporter after seeing the city I love falling apart.

The tragedy, which I read about every day from the United States, was playing itself out. And when I saw it with my own eyes in Juárez, the war’s horror had names. The dead were more than statistics.

There were also survivors. And there were still many questions to answer.

At Rockefeller Center, where I worked, I had put up photos of Juárez: its fantastic people, its magical sunsets.

I loved looking at them every day, as well as at my Mexican flag (the first flag I’d ever bought in my life). It made me feel closer to Juárez.

I decided to return to the border the summer of 2009. To live in my beloved Juaritos.

I’m a journalist. Now I freelance and write my blog from Ciudad Juárez. I don’t do big investigations. What I offer are my own portraits of everyday life in this city. Writing about what’s happening helps me feel alive amidst so much death. It’s my own form of justice.

I feel an intense and aching love: This was the first Mexican city I ever set foot in 15 years ago and my heart, born in Spain, was turned into that of a Juárez native.

In Juárez, I found a life that had eluded me when I arrived in the U.S. I was attracted to the joie de vivre of the people of Juárez, who despite the violence and everyday murders, live as if life is a fantastic moment that could end in an instant.

NAMELESS TOMBS

Thursday, November 5, 2009

The bodies that nobody claims smell much stronger. They’re also heavier.

Ramón Andiano Vargas, the 66-year-old gravedigger at the San Rafael Pantheon in Juárez, tries to keep away from them. And from the common graves where this Mexican city buries its local dead and a handful of strangers.

He’s sad. And scared. Andiano is afraid of getting sick from the foulness of a body that went unidentified for three months and was finally interned with all the others who ended up exactly as they entered their lives: nameless. To bury them, he wears a white hat and a jumper he strips off at the end of the work day and leaves on the desert sand that covers the dead. He gets paid $1,400 pesos, or about $115 USD, every two weeks. He does it to support his nine kids.

This morning I watched as he said goodbye to 16 coffins marked only by a physical description of the corpses. Fourteen dead from the drug war, two from natural causes. All men. All expired between August and September 2009.

He digs a hole in the dirt with his bare hands alongside three other graveyard workers. They use pulleys to unload the coffins from a truck, then carry them to the holes. One man supervises the process. Today it’s Ramos, an expert from the General Office of Expert Services. He’s wearing a black t-shirt with white letters across his back that spell out one word: CADAVER.

The bodies reach Andiano’s hands because no relative stepped up to the Medical Forensic Service (the Semefo, in its Mexican abbreviation) to claim them. Maybe out of fear, perhaps because they didn’t have the funds to pay for a proper burial, or simply because they didn’t know their family member was dead. If the murdered in Juárez are just another number, then those who go into the common graves are even less than that. They don’t even get a funeral with friends and family.

One hundred and thirty-nine unidentified persons were buried in Juárez’s common graves through November 5, 2009, according to figures from the Assistant Attorney General of the Northern Zone.

This is not the first post in my blog, but I wanted to begin this part of the book with it because I was touched by the tenderness with which Andiano, the grave digger, treats the nameless coffins. And because there are days in which I ask myself how many more murder victims he’s buried whose farewell didn’t include a single tear.

EL BUITRE (THE VULTURE)

There are 70 shells in the sand. He walks up wearing an impeccable white ironed shirt. He is wearing denim pants. He sees there are two bodies and the looks from the kids who smile as if they were immune to pain. He’s not sure what terrifies him more: the present or the future.

Suddenly, he sees two more bodies. Then another. Five new bodies. These are the dead. Just like in the movies. Except that they’re real.

He stares at the bodies thrown on the unpaved streets of Juárez. The door on the Nissan 2001 is open, as if they’d tried to flee and ended up in death’s embrace: one on top of the other.

A woman from the house across the street brings a blanket to cover the young people. The mothers scream, the girlfriends, the boyfriends, and he would rather not be there. He prefers dead people that don’t murmur what can never be known with precision in Juárez: who killed them and why. Groups of people climb down from the hills and scatter around the deadly triangle on the streets. They’ve come to rid themselves of the agony of doubt: They’ve come to see if any of the dead are their children.

Night has fallen.

A car scatters gunfire. It’s a Pontiac that has come thundering out of this magical and ferociously red sunset, but now it has vanished. First, they shot a boy. Then they turned around and chased a car that had two young men and some girls, all 15-year-olds. One of the girls had lost a brother a few months ago.

El Buitre approaches with care. He goes from one scene of the crime to the other, walking through the whole thing in three minutes. He tries to figure out which of the victim’s relatives is most calm. Sometimes, it only takes 45 minutes for the mothers who find themselves in this crisis to begin to understand what has happened. This is the key to his work: to know when is the right moment. He approaches.

“Please forgive me for daring to speak with you now, but it’s important that I explain what you have to do. Tomorrow you have to go to the Preliminary Investigation Office with two relatives and all your documents. You also need to make arrangements with a funeral home. If I can help in any way, here’s my card.”

Los Buitres – the vultures – are people who go in search of bodies to sell a funeral service to the family. As soon as possible. This man is a vulture. They work in silence, incognito until they feel the slightest bit of confidence. They can be very badly received.

Sometimes, the same vulture can work for various funeral homes. It’s as if he were freelancing burials. He gets a commission. The most popular service right now is also the cheapest. It’s about $4,500 pesos ($372 USD), of which the vulture will get about $500 ($41 USD) for contracting the service. Some receive a fixed salary at the funeral home, $2,500 pesos ($200 USD) a week.

The best of these arrive at the scene of the crime before tragedy has struck: They study the situation, approach discreetly, and manage to get the families to engage with them. More and more, there are “recycled” vultures who come from other professions that are disappearing just like their businesses. Among these new muerteros – that’s what they call them – there are people laid off from the assembly plants, from the discotheques, from the bars and restaurants which closed and left the city because of the violence. Few, however, dare to get too close to the scene of the crime. They work in other ways: selling their services to those still alive who understand that life is wonderful but can be taken from them in an instant. This vulture is named Ángel, a name he chose for security reasons. Because vultures are also killed.

Follow Judith on Twitter: @Judithtorrea

View her book.

Read her blog.