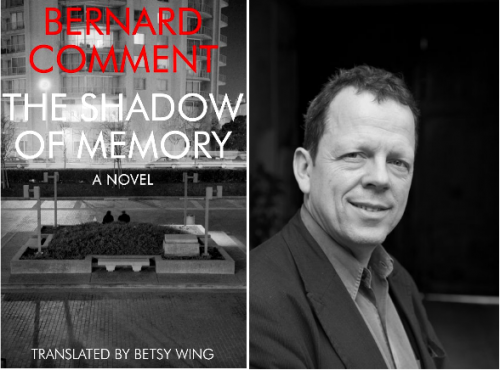

An Interview with Bernard Comment

by Olivia Stransky / December 27, 2012 / No comments

“Something essential in human life was changing”

Swiss writer Bernard Comment writes in an essay that “The history of mankind is…defined by this contradiction: to watch time pass by, and to try to count it, or to halt it.” This statement is the underlying theme of his recently translated novel The Shadow of Memory.

The narrator of the book has an obsession with obtaining as much knowledge and memory as possible and begins working for Robert, an old man who has promised to give him his entire memory. Though written in the mid-eighties and published in French in 1990, Comment’s philosophical novel touches on many themes that have become even more relevant than when the book was written, including the power of computers, the impatience of modern society, and the perceived divide between high and low culture.

The author was born in Porrentruy, Switzerland in 1950 and studied literature at the University of Geneva as well as at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris under French literary theorist Roland Barthes. Comment has written five other novels, several essays, and translated three novels. Most recently he worked with Stanley Buchthal to edit a collection of Marilyn Monroe’s writings which was released as Fragments in 2010.

Originally Comment was scheduled to read from The Shadow of Memory at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh in October. Unfortunately his stay in the US was cut short by Hurricane Sandy, and he was unable to make it to Pittsburgh. Fortunately he was able to talk to Sampsonia Way over the phone to discuss his inspiration for The Shadow of Memory, the effect of technology on culture, and today’s dangers to freedom of expression.

In an essay published in The Guardian you talk a little about your own memory problems. In what ways did your own experiences influence this book? Are there any similarities between you and the narrator?

I’m not convinced by the idea that you have to have an incredible life to create fiction, but there is probably no novel in which the author is not projected in a certain way.

In The Shadow of Memory my own experience is projected only to some degree. I used to live in Italy, and I remember being really fascinated by the way this poet I had met knew all of Dante by heart. This gave me the idea of somebody who would have a memory inheritance. Obviously this poet didn’t propose anything like that, and I hadn’t the conviction that such a thing would be possible. But it was after having dinner with him that suddenly I had found the idea for my novel. I decided immediately to work on this.

There is one experience from when I was thirteen that influenced The Shadow of Memory: At that age I took a lot of LSD, and it really destroyed my capacity for memory for some years. It also created some problems at school. Fortunately I was still very young: My brain cells continued to be produced after that, and I have recovered a good memory. I had this experience in mind when I wrote the book. But I wouldn’t want to make a direct link between my past and this story.

When did you have the LSD experience?

It was in the 1970s, and the world was quite different. I was attracted by the images around me. I had an older brother who introduced me to the idea of smoking marijuana, then I took between twelve and fifteen hits of LSD,over the course of a year, as well as mescaline. It was a dangerous experience, but it was really beautiful. Then I stopped, one year later. I went back to playing sports.

What interested me most was that for the first time the access to the memory of humanity would be conditioned by having electricity.

There are three characters in the book: Robert, who has an expansive memory of the past, the narrator, who is trapped in the present, and Mattilda, who is described as “living in the future.” How did this trio of characters come to be?

You have to remember that I wrote this text quite a long time ago, between 1986 and 1990. The world was changing, and new technology would completely change our link to the world, our link to memory, and to the past. My idea was that this change would have a forced impact on someone like the narrator, this young guy who was a little bit lost in life.

The narrator is a metaphor for that time where anything seemed possible and television—with shows like Star Academy –gave you the impression that you could be a genius without any effort. The narrator would like to have all the capacities of an old man, but he forgets that you need to live experiences before having this huge memory. Robert is the accumulation of time, a stratification of memory, and Mattilda is a part of this vibrant and brilliant life the narrator should be living.

Both the narrator and Robert praise computers. The narrator sees them as a permanent way to compile his knowledge. Robert sees them as a way for people to see the world without having to leave their homes. How do you see technology?

When I wrote the book the technology was very new, and there was very few computers. I bought my first computer when I was writing this novel. It was not difficult to have this intuition that something was going to change.

What interested me most was that for the first time the access to the memory of humanity would be conditioned by having electricity. I think this book was based on the impression that something essential for humanity was going to change. Coincidentally when I came to the US a few weeks ago, there was no power in downtown Manhattan and there was no more conversation, no more light, no more internet. I had the impression that this book had become fact. It was very interesting.

Robert sees public libraries as prostitutes because of their accessibility. Do you agree that culture is suffering because of accessibility?

Robert is a fool, he has convictions that are not my opinions. No, I don’t think culture must be reserved to one group of people. I don’t have any pure conception of culture. For me culture is a mix. For example, I have a big admiration for the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. What I like in his work is the shock between metaphysical considerations and the banality of ordinary life. I adore rock and roll and pop culture, and I think there is something very lively in the way the rap musicians in the suburbs of Paris view the French language and make it new. You can’t say that language or culture is fixed forever. Let’s open the cultural window.

The Complete Review described The Shadow of Memory as “A philosophical book-lover’s book.” How would you respond to that? Who do you consider to be your audience?

I don’t think this book is just for philosophical readers. For example I have friends with whom I play soccer, who are not literary people, but who read my novel and enjoyed it. I don’t think the book is difficult just because I put in stories about Italian art history or architecture. You shouldn’t think that people who didn’t go to university can’t read books with these kinds of references. I think it’s an open book, and it’s not reserved to a particular group.

Do you think the content of a book can be changed by translation? What does it mean to you to have your work translated in the United States?

A good translator doesn’t change so much. I’m also a translator, but I’ve only translated one author. I know that if you work hard you can be very close to the original of the text and I have the impression that this translation is really close to the original, even though the rhythms of English and French are quite different.

I’m very proud to be translated in the US because I have been very influenced by American culture and American music. When I was twelve and thirteen I read a lot. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs were a very important influence for me. Then when I began to write I spent a lot of time reading Hemingway and Faulkner. Nowadays I am following some new American writers.

While discussing lost and destroyed art, Robert says, “I say no to all you fine censors! No oblivion! No loss! We have to stand firm, against that insatiable barbarism, always ready to recommence.” What do you think the biggest threats to freedom of expression are today?

Religion, definitely religion. I was born in 1960 and when I was young I thought that we were free of religion. Then when I was fifteen or sixteen I started reading Jacques Lacan, a French psychoanalyst, and André Malraux who said that the 21st century either will be religious or won’t be. That surprised me because I already thought we were free of religious control.

I think religion doesn’t have to come in social space. There are churches, synagogues, and other sacred temples, but the public space doesn’t have to be controlled by religion. However, a lot of the world’s current problems are produced by the comeback of religion into the social space. You can see that artistic production is being controlled by religious fanatics and that too many people in the world want to have a religious fight. We have to find a way to respect religion, but we also have to maintain the respect of fundamental freedom for everybody. We have to learn to maintain a sense of humor ahead of our religious convictions.