Exiled Writer Liao Yiwu, China’s Memory-Keeper

by Maxine Case / October 3, 2011 / No comments

During the past year I’ve attended many talks and readings by renowned and talented writers at the New School’s Tishman Auditorium in New York City. While I cannot speak for all of the university’s events, at the ones I’ve attended I’ve never seen a line that snaked out of the door and into the back courtyard like I did that night. The crowd, made up of students from around the city, literary personages and other interested New Yorkers, had amassed to hear an unassuming Chinese writer speak.

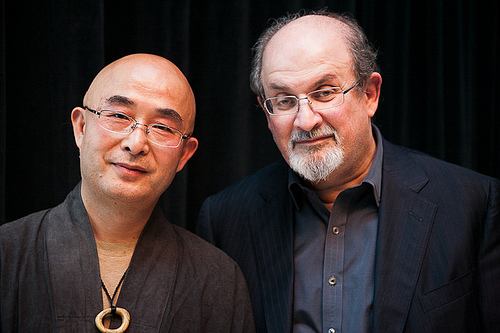

The writer was Liao Yiwu, the date September 13, and the occasion was his first U.S. appearance. It was also a makeup event of sorts. In March 2011, Liao was denied a visa by the Chinese government to attend the PEN World Voices Festival in New York. In a potent symbol to highlight Liao’s absence, Salman Rushdie, current president of the festival, placed an empty chair on the stage during its opening ceremony. Rushdie, in his opening remarks before Liao appeared on stage, said that during the seven years of the festival’s existence, the travel ban imposed upon Liao was the first time that a writer had been prevented from attending. He added that there are many people writing books in many countries, but there are “only a few people who are the real writers.” He affirmed Liao’s place in this rarefied group.

It is therefore interesting that the writer first introduced himself to his New York audience under the guise of musician. A scraping, discordant sound filled the auditorium as Liao played first his Tibetan singing bowl and then the xiao, the Chinese flute he’d learnt to play during his four year long incarceration in the aftermath of his poem “Massacre,” which was written in one night following the June 4, 1989 events known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre. It is telling that the xiao and the Tibetan singing bowl were two of the few possessions that Liao chose to take with him on his flight out of China. Interspersed with defiant singing and chanting, the performance was at once mournful and defiant.

After Liao’s musical performance, he was interviewed by Philip Gourevitch, the former editor of The Paris Review and current New Yorker staff writer. Gourevitch is a long-time champion of Liao and his work, having published a selection of Liao’s interviews in The Paris Review in 1995.

The evening culminated in Liao’s reading from “Massacre” in the darkened room while an English translation flashed across a screen. The audience was electrified; uneasy, but very definitely rapt.

A few days later, I was privileged to interview Liao in a conversation facilitated by his interpreter, Wen Huang, who also acted as interpreter for the PEN event. In this interview Liao talked about his books, his struggles with the Chinese government, and related a few anecdotes about people on the fringe of Chinese society that he has interviewed and whose stories he had recorded.

As a reader, I believe that we learn about a foreign culture through that culture’s books. Which contemporary Chinese authors should those of us outside of China read in order to gain a better understanding of China today?

There are many writers now and their works could be bestsellers in China, but because of the political environment there, they do not necessarily represent a true picture of China. If I were to recommend two writers, I think that Liu Xiaobo’s works represent the beautiful thinking in China and his criticisms of the current Chinese situation are quite good to read. Another writer is Wang Lixiong who I think offers a pretty true representation of contemporary China through his works on Tibet and the future of China. [Wang’s novel Yellow Peril was recently published in English under the title China Tidal Wave. It imagines a war between north and south China that erupts into a nuclear conflict that spills beyond China’s borders.]

I think that my work Corpse Walker is also a representation of China. This is not my writing, but a collection of interviews with people who live on the bottom rung of society. Their stories give people a true picture of China. My other book, God is Red, will enable you to learn about Christianity in China—about people’s struggles with faith.

You’ve worked as a cook, truck driver, and are an accomplished poet and writer. Can you talk about how you came to support yourself as a street musician?

Initially, when I first got out of prison, I supported myself by performing at bars and nightclubs, and on the street. I would earn money the first night and spend it the next couple of days. Gradually, I started to write books. At the moment, I live on the royalties from my books published all over the world.

In addition to banning your books, how else has the Party impeded your means of making a living from writing?

Occasionally I would go and do some music performances or I would get my works published in overseas Chinese language websites and earn some income. But the government, in addition to banning my books, would sometimes restrict my activities—especially during sensitive times. For example, during the twentieth anniversary of June fourth, not only did they restrict my activities, they also came and talked with me and forbade me from publishing my works overseas. During those sensitive times I was not even allowed to go out and perform in nightclubs.

And yet you refuse to describe yourself as a political writer? You’re obviously a political target.

I don’t think of myself as a political writer. I might be dragged into a political situation, but my works really talk about ordinary people’s lives. Corpse Walker, God is Red, and my prison memoir are more about human struggles. They are popular in Germany right now. Ordinary people read them not because they read as political works, but because they read as memoirs about human struggle and life in China.

What attracts you to writing about people on the “bottom rung of society?”

Basically, there are three reasons for this. First I was a poet. Then in 1989 when I suddenly became a prisoner, I was locked up with murderers, human smugglers and robbers, and I myself sunk into the bottom rung of society. I spent time with these people and I became more sympathetic to the people around me. The second part is that when I was in prison, these people kept telling me stories every day. Even though I didn’t want to hear their stories, they just bombarded me with them. Because of this, I became attracted to their stories. Third: Once I came out of prison and I didn’t have any way to support myself, I hung out on the streets and met street people. I began to record their lives.

What inspired you to write about Christianity in China, especially since you’re not, as I first assumed, Christian?

It all started when I spent five or six years in China’s Southwest Province of Yunnan. I met a Christian doctor who’d quit his lucrative practice in the city after he became a Christian. He went to Yunnan Province and traveled around the small villages helping people. He told me a story one day about how he operated on a cancer patient in somebody’s room—in an ordinary residence—and I was very, very touched. I just wanted to find out what prompted him to do what he was doing, so I followed him. That’s how I started to write about Christians. While I was traveling the countryside, I heard lots of moving stories. Some of the stories were about how these Christians were persecuted. During the Mao era, they were not allowed to practice Christianity, but they persisted. Christianity was regarded as a foreign religion: Christian missionaries brought Christianity and then Christianity took root and became part of the Chinese culture. I was touched by their stories and feel that the people’s struggle for faith, for the freedom to believe … There is a parallel between their struggle and my struggle for the freedom to write. So that’s how I was inspired to write a book about this group of people. I feel that their stories will enable people to understand Christianity in China.

Can you talk about your prison memoir? I read that you rewrote it three times.

The prison memoir is my biography. It’s about my life between 1989 when I was a poet and then was locked up in prison, all the way to 1994 when I was released. It is about how I turned from a poet into a witness of history. It’s about China’s prison system and this book, as you know, I’ve written three times. The one that people will read is the third version because the other versions were confiscated by the Chinese public security bureau. In this book, I recorded my life in prison. For example, I slept next to two death row inmates. They told me their stories. I was trying to record their stories about how they ended up in prison. One of them was a murderer who killed his wife. The book also details how I was tortured in prison. All these stories bear witness to what I had to go through during those four years.

How did you relate to someone who’d killed his wife?

I couldn’t relate myself to him. We couldn’t relate to each other, but I slept next to him. He was fully shackled and every evening the shackles woke me. Each time I was awake, he’d tell me stories about how he’d murdered his wife. Through his stories, I could see not only the murderer, but the raw human feelings. Gradually my mind was turned into a tape recorder and I was forced to record, to listen to their stories, and I started to record their lives. That’s why when I came out of prison, I started to write about them and that’s how some of the stories in Corpse Walker came into being.

You currently live in Germany, where you mentioned your books are very popular. Is that the reason you chose that country as your temporary home? And is it a temporary home?

I choose to live in Germany because my books are very well received there. When it first came out, Corpse Walker was one of the best sold Chinese books there, and the prison memoir, when it came out, made the bestseller list of Der Spiegel magazine. So I think that the German people really love my books. That’s one of the main reasons I chose Berlin as my temporary home. I also have a fellowship there that will last for a year, so I’m going to be there for the next year.

You’ve also said that you’re not in exile. Can you please explain what you mean?

In a way, the exile was imposed on me. I didn’t choose it. When I left China, I had a valid passport and a valid visa to attend a literary festival in Germany and to go to the US. I was forced to leave China to seek freedom to write. I didn’t realize that my book would be so welcomed in Germany and would also receive so much attention in the United States. I’m still hoping that I can go back to China in the next year, or the year after that, but this is not something I can decide for myself. I just have to see how fate is going to play out.

What does freedom mean to you?

Freedom is what I’m getting now: the freedom to talk and the freedom to write. But to me the important thing that I learned while I was still in prison is that freedom really comes from the heart, from the inside. Even though I was in prison, I tried to seek inner freedom. A lot of people, though they might live in a free world, are still not free because in their hearts they are living in a kind of prison. I just left China, this big, invisible prison. Right now I am trying to get rid of the prison in my heart and seek real freedom. When I left China, I was reading some of the ancient Chinese literature. I always get the impression that you can live in a motherland, but when you leave, you can still take your motherland with you.

If you still lived in China, who would you be interviewing or writing about, and what story do you still want to write?

If I was still in China now, I wouldn’t be able to do anything because this year was really horrible. The police were always threatening to arrest us and we couldn’t continue to write. I would probably stay at home where I wouldn’t be able to surf the Internet freely; I wouldn’t be able to interview people freely. Or I would have covered my cell phone and maybe hidden in the mountains or somewhere. This is what the situation is like in China now. It’s been the worst—especially this year—since 1989.

What are your hopes for China?

I’m not a politician—I’m not political—so I don’t hold any hopes like they do. I think most hopes are false. I’m a memory-keeper and I document what happened and what is happening now. I think that in China right now, the only thing that I would hope for is the right to continue to write. When I look at the cover of God is Red, there’s a cross with a red star on top, and I think about the spiritual life of those Christians. Maybe our hope lies in the fact that we have something to believe in—but not some kind of false hope.