Please Look After Mom: an Interview With Kyung-sook Shin

by Joshua Barnes / June 7, 2011 / 3 Comments

………….

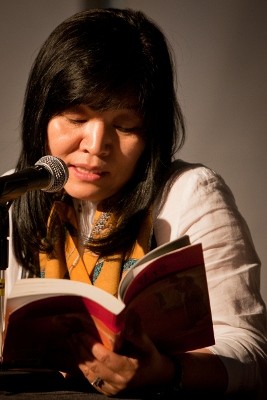

Photo: Author Kyung-sook Shin reads at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh

Kyung-sook Shin is the author of the best-selling novel Please Look After Mom. Ranked in the top twenty on the New York Times best-seller list only a month after its English-language release, the novel has also sold over 1.7 million copies in its native South Korea. Shin has written six other novels, five short story collections, and two works of non-fiction.

Her work has been translated into five languages. On May 3, the writer visited Pittsburgh to give a reading with Hervé Le Tellier and David Bezmozgis in a event sponsored by City of Aslyum/Pittsburgh in partnership with PEN/America.

Before the reading, Kyung-sook Shin and her translator Seung-hwan Shia sat down with Sampsonia Way. In this interview Shin talks about the importance of everyday love, why we need to find our Moms again, and the way that her book blends collective and personal histories.

Park-so Nyo, the mother in the novel, is traditionally Korean, yet judging by Please Look After Mom‘s international sales, she is quite relatable to English-speaking audiences. Why do you think this cross-cultural connection is so easily made?

Even though each country has different cultural backgrounds and social traditions, the word “Mom” can evoke universal emotional responses. Additionally, the behavior of children is very similar across borders. Children’s attitudes toward Mom and their tendency to forget her are similar all around the world.

Our time has lost the sense of the mother figure. That is what motivated me to write the novel and its first sentence: “It has been a week since Mom’s been missing.” I used the word “Mom” instead of “mother” because it is a very intimate word for everybody.

How does Please Look After Mom attempt to restore our missing sense of Mom?

I wanted to talk about South Korea’s cultural and political changes, in which we’ve lost the values embodied by Mom. But I also wanted to encourage the reader to see Mom differently, which, I think, is kind of new.

My focus in the novel was on making people think about why they and their societies have lost their moms. In the novel, the family has lost their mother, but even before they lost her, they had already forgotten her.

What is ironic is that mom is always too close to everyone, which is why nobody pays any attention to her. Many people think their mom was born a mother, but she is also a person who learned the word “mom” in her childhood. Mom is a real person with memories, secrets, and desires. If the reader can rethink his relationship with his own mother, then that is the beginning of finding Mom.

In the novel, love is based around the ordinary and the invisible–like Park-so Nyo, who is only apparent when she’s gone. Do you think that this depiction of love is more realistic than the fiery passion of other fiction like Lolita, for example?

The love embedded in everyday life is much more important than some specific moments of fiery passion. Often everyday love is too easily forgotten because we are so used to it. We think it’s natural to have it in our lives, and we don’t realize how great it is to have someone beside us until they’re gone.

…Side by Side: English and Korean covers of Please Look After Mom.

The novel made me question my mother and press her to tell stories I probably wouldn’t have heard otherwise. What was the process of discovery with your own mother like?

I am so glad that you talked to your mom; while speaking with our moms we can find out who we are.

Of course, this novel is not an auto-biographical work, but much of it is based on my own experiences. I left my hometown when I was sixteen years old. At the time, I only knew some basic things about my mother. During those sixteen years, I began to feel like a guest when I visited my childhood home. Eventually I had a chance to spend half a month with my mom. It was a great experience because I learned what my mom had in her mind: What she wanted to be, what she wanted to have. I also learned what scars and pains she had to endure in her life.

“Mom is like a book we cannot finish reading. She still has some pages left, even after we’ve read the last word.”

Can you explain the novel’s changing point of view? Why did you develop this structure?

Each character has his or her own image of their mom, and the novel tries to show the different aspects of their memory and how that affects their approach to finding Mom. They all have different attitudes towards their mother, but together their memories constitute the full image of Mom.

This book is not just a personal history; while I was writing it, I was thinking of the entire history of Korean civilization. Because of this, through the different voices I tried to show the many different voices and layers at work in the process of remembering.

Park-so Nyo destroys her possessions at the end of the novel: She’s trying to erase failings in her past and keep certain things secret from her family. The irony of this is that it makes her more of a Mom and less of a person…

After finishing the novel, I kept questioning, “Is this all? Did I really tell everything about Mom?” Of course, my answer was “No.” Instead, the story continues. That’s why I started the epilogue by saying “Mom has been missing for nine months.” The search for Mom is not over yet.

This novel is a story that is erased, but at the same time continues. It is very similar to the change of seasons. It is a cycle. In our lives there will be one mom, and another mom, and another mom. Of course, their lives will be very different, but they are all moms. That’s why I think a story about Mom cannot have any conclusion. Mom is like a book we cannot finish reading. She still has some pages left, even after we’ve read the last word.

How has free speech changed in South Korea in the last 50 years? Is there any topic that artists can’t express publicly?

It’s absolutely true that compared to the 1970s and 80s in South Korea, people have much more freedom of expression today: Koreans can speak their minds on almost every topic. It is also true that Korean society has come a long way to enjoy this freedom of expression, especially after our struggles with repressive regimes in the 1970s and 80s. But even though we have more freedom to express ourselves, we also face a situation where more things are complicated and invisible. When we feel repressed, it’s hard to see what problems we still have to solve.

To say it a different way: In the past, the enemy was clear and the things we needed to fight against were obvious. Now it is difficult for us to see what enemies we have. As a result, speaking has become more difficult, even if we do have more freedom of expression.

Read Sampsonia Way‘s interview with Hervé Le Tellier.

Read Sampsonia Way‘s interview with David Bezmozgis.

3 Comments on "Please Look After Mom: an Interview With Kyung-sook Shin"

It’s nearly impossible to find well-informed people about this

subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks

Trackbacks for this post