The Threshold of The Free World: Interview with David Bezmozgis

by Rita Malikonyte Mockus / May 31, 2011 / No comments

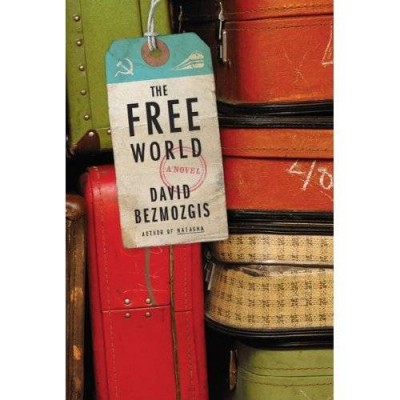

Canadian writer and filmmaker David Bezmozgis’s first novel, The Free World, tells the story of the Krasnansky family: three generations of Russian Jews who flee Soviet Latvia and head for Rome, where the family must spend six months waiting to secure visas to North America. In ironic contrast to the book’s title, the Italian capital is a threshold where the boundaries of freedom are still denied for the family.

For Bezmozgis, who was born in Riga, Latvia and moved to Canada with his family when he was six years old, the human and historical facets of the immigrant experience are an important topic. The theme of Soviet immigrants living in the free world, was also central to the author’s highly acclaimed book of short fiction, Natasha and Other Stories (2004).

On May 3, 2011, Bezmozgis came to City of Asylum/Pittsburgh to read from The Free World. Earlier that day, he spoke to Sampsonia Way about this new novel told in three voices, each reflecting a variant Soviet mindset.

A part of your novel’s narrative describes the perils of political hoax. Samuil, one of your characters in The Free World, says: “Rogues and impostors should not be allowed to qualify the essential Communist picture.” Do you think that people in the West may have a distorted image of the Soviet era?

I think that people in the West definitely have a distorted picture of Soviet life. Since this book is primarily written for the North American audience, it aims to expose the misconceptions that North Americans may hold, and to provide a factual insight into Soviet politics. The book is told in three voices in order to show different perspectives on life in the former communist country. Alex’s point of view is light and hedonistic; Polina’s is much more solid and realistic; patriarch Samuil’s is all about a steadfast belief in the moral precepts of socialist ideology.

In the novel, Samuil is referred to as a “breathing archive” of the Soviet era. His character may appear to the reader as rather cryptic and even paradoxical. Can you extend this metaphor?

Since the cold war, the tenets of communism have been so deeply discredited that nobody can take them seriously in any form anymore. There is a ubiquitous antipathy towards anything Soviet. On one hand, it’s true that at times overt brutality and evil ruled. However, it is also true that the Soviet story has been demonized so deeply that it is hard for anyone to understand now how somebody like Samuil could have believed in it so completely and blindly.

Samuil’s character is created to challenge this prejudice. He is an ingenuous, even if gullible and ideological, relic of the Soviet era. He appears cryptic only because of where we ideologically are today. To his Soviet contemporaries fifty or more years ago, he would not have seemed so paradoxical or outrageous. There were many Samuils back then. They were all part of that generation.

Your novel also mentions the idea of Soviet “compensation” for all the hardship that Jewish people had to endure in the pre-revolutionary years of Russia.

Very few people know how it felt to be a Jew in Tsarist Russia, how terribly demeaning the lives of those unwanted people were and how hopeful and bright the communist project at first appeared to them. To us, now, that kind of mentality seems very dim and distant. But the belief in the Soviet “compensation” is still fresh in Samuil’s memory. After all, he is also convinced that the communists also helped his people fight “dark and reactionary fascism.”

Communism was a powerful ideological movement that shaped the 20th century. This book chronicles times that no longer are and people that no longer live. The Soviet Union is gone. The language (Yiddish) is dying. Nothing from that era will be replicated.

Samuil asks a rhetorical question, “In the war you ran from the enemy. Now who are you running from?” Clearly, he was suspicious of a promised land of freedom…

Someone once compared Samuil to Moses who didn’t get to see Israel. I don’t think that this analogy is accurate. The irony is that the patriarch in my novel follows the dream of his family, not his own. He is not like Moses, because Moses actually wanted to see Israel. Samuil, conversely, is very skeptical about the entire project of emigration. If we follow the line of Exodus, he is more like the children of Israel who had to wander the desert for forty years. The exegesis is that the generation of slaves had to die out. Only free men could settle in the promised land of Israel. Likewise, Samuil’s inability to adapt, and his nostalgia are too strong. He doesn’t belong in the free world.

A lot has been written about the Holocaust in the West, but we are only beginning to fathom the Soviet Russian Jewish experience. However your novel would be less captivating if we only had Samuil’s ideological perspective in it. Do you believe that the accounts of Alex and Polina, which are opposed to Samuil’s, helped The Free World to familiarize the readers outside Russia with the concurrent history of Communist oppression?

Who knows, but I hope that it has. The Free World is a tale of a somewhat Herculean, at times trying process of emigration. Why emigrate, why uproot yourself, why go through all of this estranging experience if one is happy in one’s native land? For Karl, Alex, Polina, and others in the book, Soviet life was rather stagnant.

For the most part, the sufferings of the Jews east of Poland are unknown in the West. But it wasn’t very well known inside the Soviet Union. Soviet policy was to not divide the victims and so there was little talk about the specifically Jewish nature of the tragedy. Now, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the archives have been opened, and a book like this is more possible than ever before.

Your choice of genre is always fiction, but the reader may be tempted to describe your work as creative non-fiction. What would be your response to this description?

Fiction may echo real life events and thus engage the reader that way. It’s the game that the author plays and the purpose of the game is to establish a compelling intimacy between the story contained in the narrative and the reader’s own life experiences and sensibility. Perhaps Natasha, since it’s written in the first person voice, could be more easily confused for a memoir. However, The Free World is a very deliberate departure from what could be construed as autobiography. There is no true “I” in the novel. I was 6 years old when we left the Soviet Union, and for that reason, the adult voice that I may be thought to assume as my own could not be mine.

What’s next? Are you hoping to continue exploring the adventures of the Russian Jewish migration?

I am still fascinated by unexplored areas of the Soviet period. I started another book that deals with a similar theme. It’s about two men, one of whom is a famous Soviet Jewish dissident and the other is the man who denounced him.

It’s a deliberate move further and further away from anything based on my personal experience. I want to write about things that couldn’t be confused with my own life.

Writers like Pynchon or Salinger avoided public encounters. Occasionally, you also give the impression of a reluctant interviewee. There could be a myriad of reasons. What is yours?

My work is complete without me. Seriously, what do we need the writer for? The book is there for the reader to discover and enjoy it without any guidance. What really counts is the reader’s critical engagement with the novel, not what the author thinks about it.

But I am also being slightly hypocritical here. I do read interviews by my favorite writers and I must confess that I’m curious about what other writers and artists have to say about their craft.

After all, I am here today talking about my new novel, and maybe doing it not so reluctantly.

Read Rita´s Bio

Read an excerpt from The Freed World