Jean Kwok and the Girl in Translation (Part Two)

by Amanda Cardo / May 6, 2011 / No comments

“I deeply admire those who live in China and yet have the courage to speak out, knowing that danger looms over their heads.”

In a previous interview, Jean Kwok talked to Sampsonia Way about her debut novel Girl in Translation, the coming-of-age story of Kim, a young Chinese immigrant trying to make it in New York City. Here, Jean tells us about her life as a writer, her experience being a Chinese American, and her writing plans for the future.

You said in an interview with Maurice On Books that you were afraid to commit fully to writing as a career, thinking that sciences or mathematics were more secure. And yet, here you are, a full-time writer. What was the moment when you decided once and for all: writing is what I want to do?

Although I loved books from the moment I learned to read, I never dared to even dream of becoming a professional writer. Indeed, because of my poor upbringing, I was only interested in secure professions and had already worked in three laboratories before entering Harvard as a sophomore in Physics, thus skipping a year. It was only in college that I slowly began to believe that I would never have to return to the factory. Wonderful professors were teaching there when I attended – Seamus Heaney, Helen Vendler – and the world of literature came to life for me through them.

It was then that I decided to become a writer, but I wondered for a long time if I’d made the right decision. I worked on this novel for years. I didn’t know if it was any good at all until I sent it out to twelve top agents and received an overwhelming response. My life as a professional writer truly began at that moment, and I feel extremely happy to be able to work as a full-time writer

now.

Do you find that discovering the power of literature later than some was a disadvantage to you. Did you have to do anything to “make up for lost time”?

I feel like I’ve spent my entire life making up for lost time! When I was in high school, I often felt sad that I didn’t have parents who would discuss The New York Times with me over breakfast or give me suggestions as to which Shakespeare play I should be reading. That’s probably most kids’ worst nightmare! But as a working-class immigrant, I was always struggling to orient myself in this society. I longed for guidance, in both a social and a cultural sense.

I made lists of books I thought I should be reading, ranging from Dickens to Freud to Dante, and studied them in my free time. I see now that those lists contained a pretty random selection.

I had some wonderful English teachers in high school who encouraged my creative writing, but it never occurred to me to make it my profession then. I was still too close to my childhood in the clothing factory, and I never wanted to return there. Writing was just too risky. Indeed it was at Harvard that I really started studying with professors who brought the full complexity and beauty of literature to life for me.

I wouldn’t say that I suffered from my late discovery of literature, however. I was lucky to have parents that loved me and did their best for me. And I’ve had such a wonderful experience with literature, so actually I’m extremely grateful for the way my life has turned out.

Which writers have you tried to emulate in your writing? Are there any specific writers whose works have guided you in your own creative process?

The funny thing is that although I really love so many writers, I find myself unable to write like anyone except for myself. A professor at Columbia, where I did my MFA, said to me once that your voice is less something you find and more something you’re stuck with. I think that’s true. It’s ironic because I try so hard to create a compelling reading experience for my readers, yet I ultimately have no idea how my work comes across. When I first got published, the editor-in-chief of that prestigious literary journal said to me, “No one else is writing about this. What you’re doing is important.” I was completely shocked. I thought everyone else was doing exactly the same thing as I was.

That said, there are many writers I love and admire, like Kazuo Ishiguru and Maxine Hong Kingston. When I was writing Girl in Translation, I read and re-read Margaret Atwood’s Blind Assassin. I’m not quite sure why, because it’s quite a different book from mine, but I just loved her voice and the spectacular amount of craft and artistry in that novel. Wonderful books keep me inspired.

As a Chinese American, do you face pressures—internal or external—to tell particular stories and how do you negotiate that in your own writing?

The stories we tell are always shaped by who we are, whether we choose to embrace our pasts or to escape from them. For me in this book, I hoped to shed light on certain aspects of the Chinese- American experience that I’ve experienced. I know most people who work in sweatshops as children grow up to be adults who work in sweatshops. They don’t generally become writers. I feel incredibly lucky to have been able to escape the factory life, and in this novel, I wanted to give readers a glimpse of the things I have seen.

Aside from that, I walk my own path as a writer. I can never predict how my work will seem to someone else, but I know this: I only write about the things that truly matter to me. Any other type of pressure is irrelevant.

Censorship is a major issue for literature in China. How did growing up in a culture that censors its history affect your work?

Well, under normal circumstances, my family would never have approved of my becoming a writer, and certainly not of my writing about our difficulties. I was brought up to keep quiet. Our past was especially a source of shame. We never spoke about it, not even to people closest to us. However, I was very bad at being a Chinese girl. I was a disaster in the kitchen, the worst housekeeper in the world, and most of all, I wasn’t obedient at all. So when I was accepted to Harvard, my family was thrilled – not because I would receive a great education but because they wouldn’t have to accomplish the most difficult task of all: finding me a husband. I could get a job instead. Thus, my family didn’t mind when I made the decision to concentrate in English since they were still basking in the relief of not needing to convince a man to marry me.

In writing this book, I certainly broke the code of silence around poor, working class, Chinese- American immigrants. The wonderful thing is that the novel has received such a warm reception from readers and critics alike that the shame keeping our past hidden has turned into pride. People from different races and cultures have told me how much they could identify with Kimberly and her mother, and how proud we should be that we’ve overcome our past. In many ways, my family is glad and relieved that our story has been told now, even if only in fictional form.

What do you think about the increasing detention of writers, activists and artists in China?

I am appalled and saddened by the recent increase in oppression in China. My family also fled China for similar reasons many years ago, and I have been happy to see the country making strides toward democracy and freedom. However, I am shocked by the recent surge of dissident writers, lawyers and activists who have been harassed, summoned, kidnapped or put under house arrest. I deeply admire those who live in China and yet have the courage to speak out, knowing that danger looms over their heads.

It is my hope that one day, everyone in China will be able to live under free and democratic conditions.

What are you working on now?

My next novel is set both in Chinatown and in the professional ballroom dance world. In between my degrees at Harvard and Columbia, I worked for three years as a professional ballroom dancer in major NY dance studio. The book is quite close to completion now, and it’s both an immigrant and a love story. I love showing readers the worlds I’ve seen, and the professional dance world is certainly a dramatic and tumultuous place!

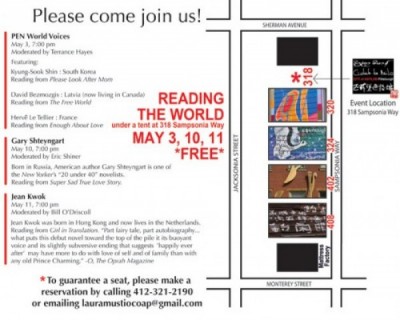

On May 11, Jean Kwok will be doing a reading and signing of Girl in Translation for City of Asylum/Pittsburgh on the Northside. Make your reservation at lauramustiocoap@gmail.com or call 412-321-2190

Click here to buy a copy of Girl in Translation

Read previous interview with Jean Kwok