Enough About Love: Interview with Hervé Le Tellier

by Roberta Hatcher / May 2, 2011 / No comments

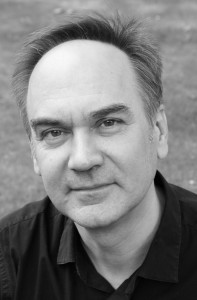

Hervé Le Tellier is a man under constraint. Not that this bothers him at all. On the contrary, he finds it to be cause for “jubilation.” He is a member of OuLiPo (from the French Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a group of writers and mathematicians who have been inventing sets of constrained rules — narrative techniques based on mathematics — to spur literary creation since 1960.

Author of more than twenty works in a wide range of genres, Le Tellier will come to Pittsburgh tomorrow (May 3) to read from his novel Enough About Love.

The novel follows the fortunes of two couples who unexpectedly encounter love at a point long after their lives appear to be settled. The women enjoy successful careers, happy enough marriages and satisfying family lives. The men, a writer and a psychiatrist, are both single and have stopped believing in a love that arrives like a thunderbolt.

Hervé Le Tellier, who answered Sampsonia Way´s questions via email, talks about the patchwork nature of a novel, his influences, and the art of translation, among other topics.

Why do you think people find it difficult to talk about love?

I know why I find talking about love difficult; I can’t really speak for others. First of all, desire, and the attraction you feel for someone, are terribly personal, and the reasons are often so deeply buried that you are tempted to say, “That’s how it is.” But that move doesn’t work once you’ve decided to talk about the subject. When love arises between two beings who don’t exist, like the characters in novels, it is necessary to be absolutely precise and to compensate for their inexistence through the indisputable truth of the words that you use. Finally, as an author you have to dare to confront mountains of literature, from Flaubert to Stendhal, and it’s hard to believe that you can say anything new. All you can hope is to find a way of telling that is personal, original and true.

So the difficulty stems from three reasons that, though different, are related. The first is of a private nature; the second, literary; and the third, cultural.

You open your novel with a quote taken from Stendhal’s Life of Henry Brulard. Your title also refers, not without a bit of irony, to another work by Stendhal, De l’Amour (About Love). Is Stendhal an important literary influence for you? Or is it this subject in particular which led you to him?

I quoted this phrase from Stendhal because it echoed what, in my view, is life’s driving force: to love and be loved. But in literary terms Stendhal counted less for me than Flaubert, as far as the 19th century is concerned; and on the theme of love, Flaubert mattered much less than contemporary writers like Roth for example. But the character of Anna does retrace some themes of Madame Bovary, while Thomas, without my being conscious of it at first, revisits the character of Bernard in André Gide’s The Counterfeiters.

One of your characters, Yves, is in the process of writing a novel titled Abkhazian Dominos. The structure of the novel also seems based on a game of dominos, where characters are deployed in various combinations of a limited number. Is this dimension of play essential to your activity as a writer?

Yes. I like to think that my texts can be read without a set of instructions, but it is true that I like when a constraint leads me away from an expected path. I am a member of OuLiPo, thus, according to the definition by [its founder] Raymond Queneau, “a rat who builds the maze from which he sets out to escape.” I’m led to write chapters imposed by constraint, and what fascinates me isn’t so much that I manage to find my way out, but rather the new narrative richness that the constraint gives birth to. I’m confronted with a text that astonishes me, even though it’s my own. It’s a rare pleasure.

Do you think this sense of play is essential to all literary creation?

No. I sincerely believe there are a myriad of different, even opposing, ways of approaching literary creation. But my method allows for a certain share of play because my personal tastes spontaneously lead me in that direction. I try, like everyone no doubt, to write the books that I would like to read.

Your character Yves finally abandons his title, Abkhazian Dominos, for one “with love in the title.” Since the word domino also means mask, one could say that he drops the mask in favor of love. Is that what your characters try to do?

Yes. But for Yves, it is not exactly love that he privileges, it’s substance. There is a struggle in him between intention and means, between what he wants to express and the technical artifices he uses to say it. He finally stops hiding out of false modesty behind form. He finally puts “love” in the title and abandons those blasted Abkhazian dominos.

You write in a wide range of genres: poetry, essays, journalism, short stories. Is there something unique that writing a novel allows you to do?

The novel as I conceive it allows for the integration all other genres. In Enough About Love, I managed to slip in poetry, a song, an academic lecture on the origins of language, a novella, a book within a book, and miscellaneous information touching almost on the encyclopedic. It’s not a conscious intention; it’s a simple fact that imposes itself on me as the book advances. I like the varied levels of language in the texts, and the possibility of jumping from one to another.

According to the biographical note, you practice a number of other professions besides writer: journalist, professor, mathematician, food critic. Does this mean you engage in all these activities simultaneously, or have you abandoned some to devote yourself fully to writing?

I’m no longer a food critic, alas. It was a fun activity that I engaged in for five years. I gave up mathematics at age twenty-four to turn to journalism. I don’t do anything today but write, in a sphere fairly close to literature, including my daily post on [the French newspaper] Le Monde. A few hours of university teaching a week keeps me from staying home eating pastries while staring out the window.

How did you begin writing?

I came to writing very young, like every author, I think. At age thirteen or fourteen I wrote little stories and poems that I showed to my friends. They were very naïve writings that I found years later in a box. I returned to writing when I was thirty, first by way of the novella, since a novel required time and I had too little. Then, with my entry into OuLiPo, I devoted myself to writing full time.

Have your works been widely translated?

I’m translated in a dozen languages, though I have few books translated into English—there will be five by the end of 2012. Enough About Love was the first published by Other Press, and [translator] Adriana Hunter did marvelous work.

Ian Monk is my other translator for two books published by Dalkey Archive. He is a member of OuLiPo, and he tangled a bit with a complicated work, A Thousand Pearls for a Thousand Pennies (a title that has nothing to do with the original French title). “Oulipian” works are difficult to translate, such as La Disparition by Georges Perec, a book in which the letter “e” never appears, translated by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void. But my books are not “linguistically” oulipian.

What do you think of the art of translation in general?

To translate is to betray. Traduttore, tradittore say the Italians. The art of a translator is less to translate a sentence than to strive towards the same point that the original sentence tries to attain. Sometimes it’s impossible. Charles Trenet sang “Le soleil a rendez-vous avec la lune” [The sun has a date with the moon] and we know it’s a man waiting for a woman, because in French, sun is masculine and moon is feminine. That meaning is lost in English, and reversed in German, where moon, der Mond, is masculine and die Sonne is feminine.

Are there any contemporary writers that you particularly enjoy reading?

I was somewhat late in discovering [Chilean writer] Roberto Bolaño: 2666, The Insufferable Gaucho, etc. and that’s what I’m reading right now. He is very close on a number of levels to an Oulipian writer like Perec. The playfulness, the false erudition, the real virtuosity. I don’t know his poetry well, unfortunately. It hasn’t yet been translated into French and I don’t speak Spanish well enough.

You are one of the “papous” (elders) of the famous France Culture radio show and your novel showcases various forms of oral performance. Do you prefer readings and public events to the more conventional view of literature as a private activity?

The writing phase is always solitary. But certain texts lend themselves to oral performance, and I like to be able to present those to the public. The OuLiPo readings in Paris, which gather about four hundred people every month, sometimes provide the opportunity. On such occasions I admit I prefer to make people laugh rather than cry.

Read Roberta’s bio

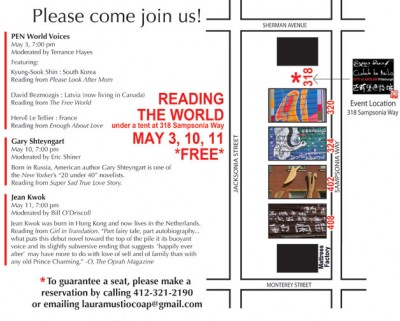

Tomorrow, May 3, Hervé Le Tellier will visit Pittsburgh to give a reading with Kyung-Sook Shin (South Korea) and David Bezmozgis (Latvia, now living in Canada). The event is sponsored by City of Aslyum/Pittsburgh in partnership with PEN/America.

CITY OF ASYLUM’S INVITATION FOR MAY LITERARY EVENTS: