Talking Back to Nabokov: An Interview with Akhil Sharma

by Elizabeth Hoover / July 21, 2010 / No comments

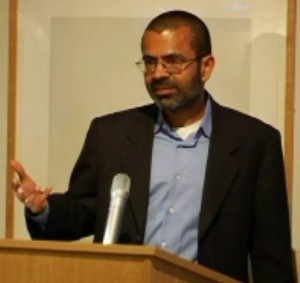

Born in Delhi, India, in 1971, Akhil Sharma immigrated to the U.S. when he was 8. He is the author of one novel, An Obedient Father, for which he won a PEN/Hemingway Award and a Whiting Writers’ Award. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, and Best American Short Stories and have won several O. Henry Awards. His short story “Cosmopolitan” was made into the acclaimed 2003 film of the same name. In 2007, he made Granta’s list of the 21 Best Young American Novelists. On April 29, Sharma visited Sampsonia Way to give a reading sponsored by City of Asylum/Pittsburgh and the PEN American Center. While he was here, he spoke with Sampsonia Way associate editor Elizabeth Hoover about the value of fiction, his relationship to his characters, and learning how to write about Indians from a white man.

For me, one of the pleasures of reading your work is getting to know your characters. When I read your short story “Cosmopolitan,” I went from thinking the main character was just a silly guy to really respecting him and feeling tender toward him. Do you have models for creating such rich characters?

I grew up with the literary tradition of mainstream early 20th century fiction. I learned writing by copying writers like Hemingway. One of the dominant ideas of that period is that the only thing that matters is the stakes in the character. Literary fiction that aspires to be great fiction wants to make the character as real as possible and to grapple with ideas that are as real as possible. Most human beings are somewhat unattractive, or we misunderstand ourselves so we judge other people harshly and unkindly. I try to make my characters as real as possible, so I present flawed human beings. If you get to know a silly person, eventually that person starts to matter because they are a real person.

Ram Karan in An Obedient Father isn’t so much silly as repulsive—he molests his young daughter. What sort of challenges did you face when trying to inhabit that character?

I grew up with a very guilty conscience. I have an older brother who is severely brain damaged. Right after his accident, I started school and it was very shocking to go to school while my brother was in the hospital. I was very aware of how different our paths were. When I would cry, the teacher would send me out to the schoolyard because I was disturbing the class. I would walk around and have long conversations with an imaginary God. In one of these conversations, God said to me, “If you could change places with your brother, would you choose it?” I immediately thought no. Then I thought I am very bad, and I can’t be trusted. Getting to the point of view of a guilty person wasn’t hard because I was a guilty person. This character sees chicken pecking at shit and he has an image of putting shit in his mouth. And I have had those horrific images. So I took my guilt and I grafted it on to a crime and then I let those two things grow together.

You must have thought about Lolita while writing that character.

Lolita is an extraordinary book and a great book, but the challenge of appreciating Humbert Humbert is not made fully real because we don’t watch the crime. So I wanted to make sure the crime was apparent in my book. When Ram has sex with his daughter he puts newspapers down on the cot because she bleeds. Later, when he touches a doorknob it makes him flashback to the feel of his daughter’s pubic bones.

One of the things that struck me about those recurring images was the way it resembled how victims of trauma are haunted by that event. One of the most uncomfortable things about the book is that it made me consider the perpetrator as someone who has experienced trauma.

I think that one can experience trauma without having traumatic events occur. In the chapter where we learn the details of the molestation, we also learn his full story: his mother’s mental illness, his father’s alcoholism, his mother’s death, the abandonment he feels. Very bad things happened to him, but many bad things happen to plenty of people and they don’t become child molesters.

How do you stay true to your characters’ cultural landscape without collapsing to ethnographic literature?

I wanted to write and I didn’t know how to write about anything I knew. When I started writing, I wrote about white people doing white people stuff even though I hadn’t even been in a white person’s house until I was in high school. I wrote about white people, because that’s just what I thought fiction was. Because Hemingway only writes about exotic things—people abroad, gangsters, or children seeing trauma—I learned from him how to handle exoticism. If you can make the story urgent enough you can start putting in exotic stuff and not overwhelm the story. I learned from him how to put in foreign words without it being false. I learned how to break up descriptions of things over the course of a page so a reader will know exactly what is being referred to. That is how I learned how to write about Indian characters.

How do you respond to the criticism that because you write about Hindi-speaking characters in English your fiction is inauthentic?

The only language I know well enough to write in is English. One could argue that that enterprise is false, but for me fiction is false. When I first started reading, I read Robinson Crusoe and he would walk into a room or a cave, and I would think, there is no cave, this is just words. Everything is made up. But if you are saying you aren’t representing it as best as it could be, that’s true. A better writer than me would write about it better. I just do the best I can.

How does the idea that fiction is false jive with what you were saying earlier about making characters real? Everything about fiction is false. The only thing that isn’t false is your experience of it. Let’s say you read a bad novel, but you find it moving and fascinating. That is a real experience. I have nothing to say about that. What I try to do is present what I think is valuable. To the extent that you find it valuable then that’s not false. To the extent that you don’t find it valuable…well, it’s not false it’s just irrelevant to you.

Can you say a little bit more about what you think is valuable in fiction?

We all have sorrows and worries. We all have doubt. We all feel a sense of uselessness. The guy in Papua New Guinea who walks around covered in blue mud and you and me. There is a way to weave together the specificity of people’s lives with what is universal. They can both act as currency; the exoticism of the fellow covered in blue mud and the universality of him mourning his child’s death and saying, “I have begun to love my sorrow because it reminds me of him.” Fiction for me is about asking what kind of good can I do in the world. Fiction does good in the world because it shows us the world and it gives us an insight into other people’s interiority. I think fiction is a great good.

Yet it is inherently limited because it is, in a sense, false.

No book can be everything. But I don’t think that books claim that. Books only claim to be telling this particular story. To ask it to do more is to try to build a house out of water. It doesn’t make any sense. The experience that a book offers is a very specific experience, and there are limits to it because we are all different. I can write about my mother’s experiences and make her credible and I can get you to feel a lot of what she feels, but I can’t give you all of it. Books are only talking about shared experiences; they are not talking about being complete and being everything. In some ways, a book also requires the reader to be brave, to step out on the bridge, and meet the writer halfway.

Read Elizabeth’s bio.