The Luxury to Express One’s Feelings: An Interview with Housam Al-Mosilli

by Kayla Bloodgood / April 24, 2017 / Comments Off on The Luxury to Express One’s Feelings: An Interview with Housam Al-Mosilli

When you talk about labeling, it reminds me of the problem of generalizing the conflict in Syria and what it means to be Syrian that you’ve talked about before. How do you try to respond to overgeneralization with your writing?

I’m trying to get across that Syrians– or anybody of any nationality or race or anything in the world– we are in the first thing individuals. Each of us has our own separate and important story. Each human on this earth has his own very important life to tell about, and he is not the same as his neighbor, or his brother even. I witnessed something other people have witnessed, but each individual has his own point of view. Sometimes we share something like politics, or economics, but we are very different. It’s a matter of people who can express themselves, and I think art is usually good for when you want to express something or when you want to fight generalization.

We are in the first thing individuals. Each of us has our own separate and important story.

I remember there was an animated Iranian movie nominated for the Oscars maybe three or four years ago called Persepolis; it’s about an Iranian writer living in France, and she decides to go back to her country. She speaks the truth there: that all the people are individuals– they have their own story, their own life, their own careers, and she was one of them.

We can’t say “Iranians”, or that the writer of this movie, with her own story, will speak for everybody in Iran. Maybe if you went to Iran you would think that some things are the same, but definitely the people aren’t all the same. And that’s what I’m trying to do when I’m writing short stories. I’m writing about very different people sometimes. I wrote two different short stories about the army and soldiers. And one of the soldiers was pure evil and the other was an angel. One was helping people and the other was killing them. Even for the soldiers, we can’t say that soldiers are the same. They are humans first.

How much of your work has been translated into other languages?

I have a few translated texts: some longer texts, some poetry, and some nonfiction texts. I have a short story that was translated into Swedish. I have several texts translated into other languages, but mostly to Swedish and then to English. When I was in Istanbul, I wrote “The Memories of the Lost.” I remember people liked this text a lot, but still– actually I did not like it when “Diary of the Silent” was translated, for example. When it was translated to Swedish first and then English, a newspaper in Sweden wanted to republish it. So it was republished here. And then at the Courrier International in France, one of the editors read it in Swedish and he wanted to translate it into French and publish in the Courrier. This text has been translated into several languages. But I don’t know how I feel about it; I’m still confused about it.

Do you feel like something is lost when your work gets translated into other languages?

Yes, of course. I have already translated four books. I just delivered the last book three weeks ago to the publisher, and I know how hard the translator worked on it. However, the original text will never be the same as the translated one.

When Your Home Leaves You: Life in Sweden

You’ve said you spend about six hours a day watching the news. What are you looking for when you watch? What kind of material are you gathering? What kind of effect does it have on you?

I watch the news with fear because every time I watch the news, I’m scared I’m going to see someone I know among the victims and people who have been killed. Sometimes I think maybe I will see some report or some video, and I will see that my apartment has been bombed. Still, I also watch the news because I think I have to do something, and I am still concerned about what is happening in my country. I still know what is happening, both the events on the ground and in the political field. If I stop watching the news, I think I would mostly be lost. I’m always in contact with people inside in Syria and trying to stay connected.

For me in Sweden now, I’m really enjoying it. After living in several countries, like starting from zero, I think I’m going to live here for a long time. Based on my experiences after about 13 months here, I think it is a very good country; the people are very shy, but they are also very kind. Now I’m focusing on being settled in Sweden. So that’s why I started going to school, learning the language; I already applied for the University– I want to study documentary filmmaking. I’m trying to find work here– not only my freelance work– I want to find something that I can feel very settled in the country, going to spend every day at work with a group of people. I think Sweden has given me the greatest opportunity I can imagine. Of course I’m very grateful for Sweden. Even for this potential to be the guest writer, it’s something special and so all of the time I feel that I owe them, and I should at least do something in return. That’s why in the last year I have been going every week or so to a reading or lecture, or visiting something all around Sweden. They were very pleased with me; I’ve been invited to a lot of activities, and I’ve been given the chance to just tell about my country with all the freedom, with all the words I want to tell with.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on translations of my short stories, and the novel– which I stopped writing—I’m going back to it again. I was working on a TV program about cinema, I did two series of this program, about 26 episodes. The first season was about the political films and asked questions about how we are telling stories in the western world. Western films try to help or force a story, especially when it comes from Iraq. You see this in a film like American Sniper. The second season was an anthology of the best cinema in the world. I wrote a lot about Fellini, Hitchcock, Scorsese, Spielberg, and I’m trying to publish it as a book now. There’s a lot of things I’m still working on, like I’m translating some of a book– they are articles to publish as a book– it’s all about cinema, and I’m translating it from English to Arabic. It’s a very hard language because it’s not like English.

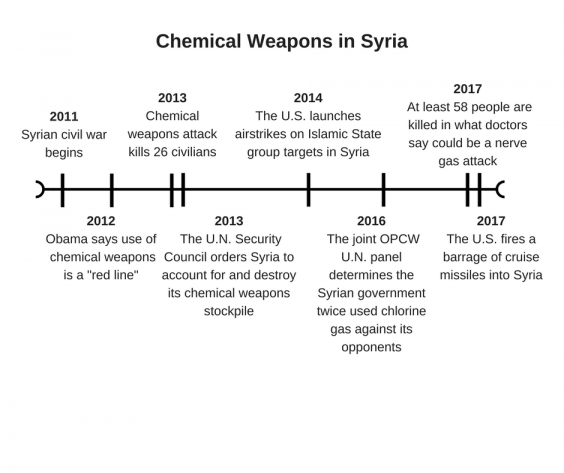

Timeline Dates from TIME online

Do you think you will ever go back to Syria?

Well, to be realistic, I don’t think so, or at least not in these next ten years. I always dream of going now, like we hang up and I say goodbye and go back to my country. But then to be more realistic, I know that I’m staying here. Even in Syria, I think it will take a lot of time to reset that place again. Instead I try to do something much better than living in the country and not doing anything, but instead living outside the country and telling the story of the country and trying to be a good representative outside of it.

There’s a lot of conversations about refugees in our global discourse. But you’ve said no one talks about the “real problem” of getting rid of terrorism in Syria so that Syrians can return home. What do you think is the answer for getting rid of terrorism in Syria?

The main root of terrorism in Syria is the regime of Assad. It has been for forty years. Before Assad, the women were educated, we did not have to ask for a visa to travel to other countries– we were a very open-minded society with more respect for human rights. We were a very complete country, but they ruined it; they stole it from its people during this dictatorship. I think — I’m still always insisting about this—that getting rid of Assad will fix maybe 75 percent of the problem. Now it’s really complicated. When we hear the news outside Syria and we don’t know any sources on the ground about what is actually happening there, you will see that the international community is not trying to solve the problem, they are just making it worse than before,. We now have the Russians, and I think maybe the whole world, involved in the war.

I’m sure what I’m saying goes for most of Syrians: they blame Barack Obama for not taking any action. Because people were saying, “Come on, the American President is going to protect us.” They had a lot of hope in Obama. And he was saying every day that Assad had only a few hours to leave power, and we people had hope that we were supported by the biggest superpower on the planet. Then he abandoned the people. After he said, “We are not going to attack Assad’s regime,” the victims killed by Assad increased from dozens into hundreds. It was like they had the green light from America to do what they want.

The main problem is still Assad, and But the main problem is still Assad, and actually according to statistics, 92% of the civilians killed in Syria have been killed by Assad’s regime. And 1.8% of civilians were killed by the ISIS and other extremist Islamic groups. It would be silly to put our hands now in the hands of the killer Assad and say, “Let’s go and fight ISIS.” The world really should always have a third option, so we can say more than that we need to only fight ISIS or for Assad to take the country. No, there’s 20 million people in Syria. And I’m sure we can establish a new government and we can elect a new government to rule the country.

What do you think is Syria’s future?

Everyone now on the ground is saying that the country will be divided and maybe in ten years there won’t be Syria as we know it. There will a country for Alawites, a country for Sunnis, and Turkey is going to take some part of the country, and maybe Israel too. The Iranian influence is also spreading wider and wider. And I think the Iranians– the government of Iran– they are the most evil in the Middle East out of anyone. I think if nothing happens to change that dark future, the whole world is going to suffer. We have already witnessed how people are using– some terrorist people– are using the cause of human rights in the Middle East to justify terrorist attacks. That’s why I think all of the people who really believe in human rights should be protected in my country, in a democratic, liberal, or whatever it is, some government elected by people. We need support to find an ultimate solution for all of this that’s happening in the Middle East, especially in Syria. But still, it’s not a matter of feelings only.

The most powerful people on this earth are actually the most evil. They can control the economy, and I’d like to think that even before there was war in the world, there were still those guys who try to steal or terrorize, and those people are now just wearing some nice tuxedos and makeup, and they can go in front of the cameras and speak, and they can go and control the military. But they are still the same, because it’s the human race that should be looked at. When people choose who their leaders are, they only want to go by appearances. They do not look for the people who can help us all live together.