The Excavation of Identity as a Political Act: A Conversation with Helena Maria Viramontes

by Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder / January 24, 2017 / No comments

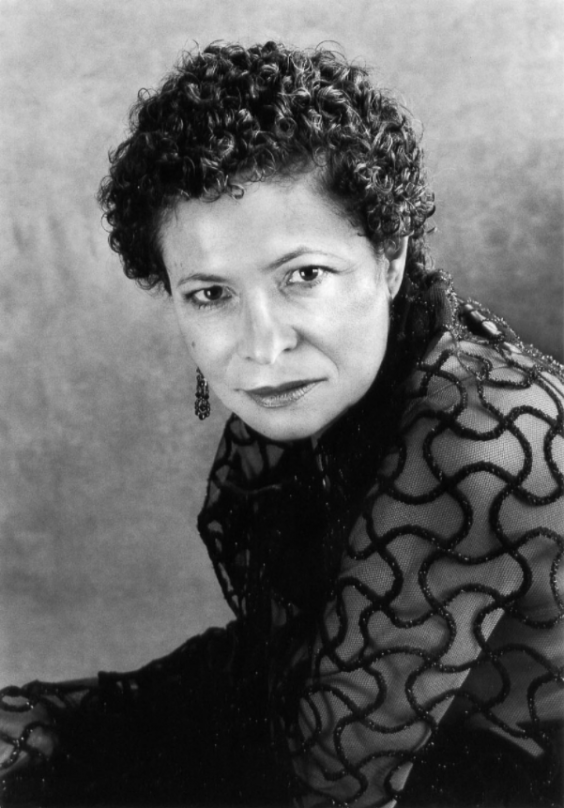

For nearly four decades, Mexican-American author Helena Maria Viramontes has been telling stories about the issues that are arriving at the forefront for a wider swathe of Americans today: stories of economic inequality and civil rights in marginalized communities. Her stories are rooted in the impact of labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez, the United Farm Workers Movement, and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s upon her family and community. Her characters, predominantly impoverished women and children, are resilient in their unrelenting love of life and all of humanity. Her writing is indispensable for this new political era of Trump.

Less than one week after the results of the 2016 US Election, writer Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder interviewed Viramontes for Sampsonia Way Magazine and Aster(ix) Journal. The two Latinx writers spoke about social movements past and present, families, and the interconnected histories of minorities in the United States in a wide-ranging and revelatory political conversation.

Elizabeth Rodriguez Fielder: We first met on the night of the election at the City of Asylum reading, and now we’re meeting again under very different circumstances. For the duration of your career, you’ve been writing about and defending the very people that are being directly attacked by our president-elect. Now you are here in a place called City of Asylum. If this were in a book no one would believe it! It’s almost too poetic to be real. And I’m wondering, how have you been reflecting and processing that throughout this post-election week?

Helena Maria Viramontes: I just talked to a good friend of mine, Sanjay Mohanty, an incredible colleague for me at Cornell. I said to him, I couldn’t have been in a more perfect place, and I was so grateful to be here exactly at this time of great upheaval and nightmare. I spent so much time on Facebook on Wednesday just scrolling and reading posts from the people that were scared, the people that were frightened. The one that got to me was this BBC posting of an interview with kids in a third grade classroom. It had to be in Texas. The kids were very outspoken about how they were frightened about their families being torn apart and two or three of them just started crying. And that’s the only time that I broke. I really broke. I started sobbing myself. Because I’ve always felt that it’s our duty as people who don’t have that fear, who have the luxury of not being afraid, to speak up.

There are all these different demonstrations that are going on like, Trump is not my president, and that’s good because there’s no real message other than the rebellion against the election. But the fact is—I think—they are doing that out of solidarity, out of collectivity. That energy people have when they’re together make them less afraid. They become more politically savvy and mobile. Right now, that’s just the knee-jerk reaction: go out into the streets. Without any mandates, without any real organization, without looking at the best ways to organize this resistance. But I do feel that’s good. Especially the students. Especially “the Dreamers.” That collectivity really does feel like something can be done. That my body, that being here, is worth something. That me being here is a good enough protest.

ERF: The current fear can be productive because it’s a moment for understanding that there are people that have been experiencing fear regardless of who the president is. Privileged people suddenly feel afraid, creating a chance for empathy with communities that were oppressed before this election.

HMV: One of the reasons I like Facebook is because so many people were responding to the election. And the disbelief and the shock and the fear just went on and on. But several months ago, there was one posting that I do remember that said, This is exactly why there should be more ethnic studies, courses, more alternative literatures, as part of the mainstream in order to expose, to educate. How else but literature can you feel that empathy? It’s the true power of transformation. Toni Morrison calls it the dancing of the mind. Paul Auster says that the most intimate relationship two people can have will be the reader and the writer. Complete and total strangers enter into these particular worlds, the writer’s world that the reader has the permission to enter, and complete that act of art.

I think that’s one call. For example, as a scholar of these literatures, you are called on to become more vigilant, more assertive, and more argumentative about the necessity of having those courses. Part of the wonderful experience of teaching creative writing is that each course is everything and creative writing. It’s an examination of the Self and an examination of each other. It is about morality, politics, character, the senses—these wonderful and beautiful things.

There was this student in my class who had written a story where the character didn’t rise to the occasion of being a hero and speaking out. It was about his grandfather, who was next to a concentration camp, his grandfather who was by-and-large silent while living in the occupied communities around the killing camps in Germany. There were several students that objected and said, This is not historically true, people just didn’t know what was going on. Then I said, That’s very well and true, that could be very historically accurate. Also, this person has the right to write what he or she wants to write. And I added, Let’s all look at ourselves for a little while here. How many of us would rise to the occasion? We all think we’re going to be the noble people that will rise. But I experienced the 1980’s when the AIDS epidemic went on and nobody cared. There were just gay men dying left and right, who cares? It moved to drug addicts, then prostitution. Oh, who cares? But then it moved into hemophiliacs, and all of a sudden it’s like, Oh my god the innocent! So I said, Please don’t tell me that we can all rise to the occasion, really think about that.

ERF: When reading your characters, I see them struggling through a generational gap, linguistically and culturally. As a first-generation American, I find it difficult to connect my own politics with my mother and my extended family. I’ve sought out role models in different places such as school, but I know a lot of young Latinx people out there who don’t have access to the kind of support system I did, and they can face parents with strange political opinions. What is your advice—or perspective–you might offer for young people that are finding it very difficult to talk with their parents at this point in time?

HMV: Wow, that’s a big question. For my own experience, I guess my mother was very unique. She was born in this country. In fact, all of my mother’s family was born in this country, except my grandmother and my grandfather were both born in Mexico. And my Tia Andi, who was the oldest of our aunts who died around 1990—she was hitting those nineties—she was born in 1904—I have her birth certificate. They grew up very Americanized, in West Los Angeles, and even though the community was very Mexican, they grew up listening to radio shows, being very much influenced by movies, by things like that. So between 1920 and 1940 it was very interesting time, where they were really trying to discover what it was to be American, even though my grandmother and grandfather were Mexican. It was a time that I’m excavating myself in my work because it was such a transition for them.

My mother was very different. She was raised Mormon and converted to Catholicism to marry my father. Though she had an altar at the house that my father built which is where I got the inspiration for Under the Feet of Jesus because any important paper she literally would put under the feet of Jesus. But she was never somebody who told us that we needed to go to church or imposed Catholicism on us. In many ways she had a great belief in God, but she was not of the institutions. I guess part of it had to do with getting away from the Mormon Church, the other part of it had to do with not agreeing with the Catholic Church, either.

My sisters and I didn’t understand how unique they were in their resistance. Whatever my mother’s politics, whatever my mother’s religion, I saw that she was a creative woman. I acknowledged that not everyone saw what I saw. That was one of my primary inspirations for wanting to write about women, especially the women in my family. My sisters were very rebellious, but only within the confines of their jailed household. My father believed in curfew, in women not going out on dates without chaperones, but my sisters rebelled creatively—and with my mother’s help, too! If they would go out with a boy, my mother would be in the kitchen waiting in case my father woke up.

ERF: Yes! When I look at the people surrounding me in my life, I find that I’m not drawing religious or political influence, but rather things like creativity, or a tone of voice that I admire and I can adopt even in a totally different aspect. Many of these moments happen in silence, like watching your mother at the kitchen table. It is a way to potentially connect together across generations despite cultural gaps.

HMV: Right, and in doing that you develop a sense of respect. And you know my mother and sisters were just astounded that they were given these kinds of spaces in my work, honoring and loving, because nobody wrote about them. So I was going to write about them; in a very truthful way, not in a romantic way. And then, because of that development of respect, then you can sit down and have conversations. And that’s what I did.

I do have some very conservative family members, but I have faith in their intelligence. I have a wonderful sister who I respect who is so smart. I realized we couldn’t talk politics because I just didn’t understand. But then, slowly things would happen, like they just laid off all these people in the company your husband works in, and yet reported a trillion in profits. Because I trust her intelligence, there’s a poco that rises up in conversation.

ERF: I feel like we have to be brave to sit down and have a small conversation.

HMV: But that’s what they are they’re small. You just begin with small conversations. That’s all. You just have to trust in people’s intelligence, which is what I did with my sisters.

ERF: Your talk of unions warmed my heart, since being a union kid changed my own life. Aside from all the medical benefits, we had cultural discounts that opened doors and a sense of community. However, the traditional model of the labor movement is shifting and changing today. Obviously, Under the Feet of Jesus is taking place at the time of Cesar Chavez and the farmworker’s union and you wrote about the hazards of the workers—they do exist today, but in different ways, like in the meat industry and the construction industry. However, we are also seeing the rise of worker centers. How you see labor today? Do you have hope for the labor movement?

HMV: Yes, I do have hope for the labor movement. Right in the middle of writing Under the Feet of Jesus, Cesar Chavez died. So I just felt I had to insert him in, and I kept writing these very symbolic chapters, about the sun going down as we’re walking out into sunset—very dramatic—as sort of a tribute to him. But, it just didn’t click. Part of the reason was because I wanted to tell Estrella’s story, and I didn’t want to tell mine. And there was a big difference. Working in the fields myself, it was just natural that I would be in the United Farm Workers support group. But not for Estrella. So I just thought, I’m gonna hold back and not include that. I also didn’t want the workers’ struggle to take away from the workers, which can happen. I felt it necessary to actually see people working, describe people working. People can talk about sweat, they can talk about the hardships of working in the fields, but to actually see them doing that in a very systematic way is something you don’t see a lot in literature. So I wrote a whole section about working so people could understand what it takes to pick the grapes.

When Under the Feet of Jesus first came out, I was asked by a radio interviewer in one of the New England states, This novel is about farmworkers, it’s about the poor, can you make an argument for why people should care?

ERF: Wow.

HMV: Tell me about it. I was taken aback.

ERF: Would you answer, Uh, humanity? The fact that we both have veins with blood coursing through them? The fact that it’s completely arbitrary that you were born in one life, and not in that one?

HMV: Yeah, thank you! It was so strange! So I immediately thought, well all I can say is, have you eaten an apple today? Are you going to have a salad for lunch? Are there buffets where you can pick your vegetables? Are you going to have string beans for dinner? And I said, and who do you think picks those? Every one of the vegetables and fruit I mentioned has the handprints of farmworkers. And that’s why you should care. I was so astounded but it woke me up too. Not everyone’s going to understand that.

ERF: Do you see that lack of understanding as a part of our society and our culture–especially at a level of privilege—where people are very distance from even the process of growing things? In some ways I see it as a conduit to activism, to understanding the processes that go in and supporting in some way the environmentalist movement’s call for local and small scale.

HMV: Absolutely. In fact David Vasquez and Sarah Wall interviewed me for a book on ecocriticism. Part of what they’re talking about is the divorcing of the food systems, so that agribusiness can come in and do whatever the fuck they want. So you have these horrible slaughterhouses that Wall writes about or that Fast Food Nation writes about. What I like about Sarah Wall’s work is that she takes to task the author of Fast Food Nation, who describes these the chaotic, filthy industry but overlooks the mejicanos doing the work. In her argument, she’s saying, he’s concerned about the cruelty toward the animals, but what about the cruelty toward the workers?

ERF: The cruelty to the workers is the reason why I’m vegetarian. It gives me an opportunity to speak about the people being exploited in the factories. That could have been me if I was born under a different set of circumstances.

HMV: It is very serendipitous. That’s the scary part about these lives of ours. I almost dropped out when I was in the eighth grade. Both my sister Frances–a year and a half above me–and I stopped going to school. So my mother—knowing that my sister was out in the streets—stayed home. But she had us cleaning left and right. And after about a couple of weeks I thought, man I don’t want to do this! Maybe I’ll go back. And my sister did end up dropping out and she did end up cleaning houses. Until my mother–see she was very Americanized–found a job course and they had programs for at-risk youth and so she sent Frances there and Frances was able to work as a nurse’s aid and then get a nursing degree. If I had dropped out, who knows? If it wasn’t for a drama teacher who I just loved…and I loved drama. So I went to Garfield and I pursued that. I even wrote a play. Who knows what happened to it, but that saved me.

ERF: Theater becomes a way of allowing people that normally wouldn’t, to come together. Since your reading at City of Asylum, I’ve been thinking about Filipinos, who were involved in the migrant workers struggle and even performed on the picket lines with them in El Teatro Campesino’s plays. There are so many groups on the border of Chicana/o and Latinx identities, right?

HMV: Right, just like these Punjabi workers! The more I do research on it for my book, the more I see the parallels.

ERF: Could you talk about how those parallels could be mobilized within the movement? How might different ethnic groups be able to come together in a productive way?

HMV: You know, I don’t want to be a reductionist, certainly not an essentialist. I was doing research for this book in South Central in L.A., where the neighborhood had completely transformed from African American to Central American and you can barely see the traces. You see a little sign that says, South Central was once the jazz quarter of the world, and that’s it. Just like on Chavez’ grave, they have a little pot of flowers and that’s it. It’s dismissed, it’s buried. Fast-forward to a couple of years later, when I’m invited by USC along with Dana Johnson and Héctor Tobar to talk about race. It was a writerly panel for writers who write about race, but it was publicized differently and the place was packed with at least 200 people, most of them teachers and students and professors. After we each did our presentation, there was a black woman who got up and said, I brought my students here, this was very disappointing. I thought we were really gonna talk about race. She said, Do you realize how violent it has been in the high schools? Where there’s been Latinx and Black violence time and time again? So I thought maybe we could really have conversations like that. I just said, We’re gonna really have to think about vocabulary to start these conversations.

If we know each other’s history, we will be able to see parallels in this history. If the black students knew about the Jazz Quarter and the incredible historic events, I bet they would feel a certain pride. And the Central Americans would understand that there was a transformation and maybe have a little respect. Perhaps then there would maybe be more conversation between them. But if we don’t find those parallels, there’s going to be an incredible war.

ERF: Absolutely, and that must be a lot of pressure for you as an author when you sit down to write. To try to encompass all of these different backstories, and these different histories, in order to create those parallels in your work. But how are you handling the stress of that?

HMV: It’s very stressful, and the worst thing that anybody could tell me is that I’m writing a stereotype, or that this is just expository. It’s a real challenge, and yet there is beauty in exploring these types of lives. I have this Punjabi character who meets a Mexican woman in El Centro, and they’re going to get married. In California, it wasn’t legal to have interracial marriage. So they have to go to Gallup, New Mexico on a segregated train in 1935. In the “Coloreds Only” compartment, he looks at a black woman with a headwrap and he smiles because he’s wearing his turban. And she smiles, creating a little moment. As they’re traveling, he starts to reflect and understand segregation because of colonized British India. Many of the Punjabi men were actually military men that were under the British Indian Army because they were known as warriors. They have lion hearts. I imagine he’s part of the British Indian Army of which 65 percent of the men came from Punjab. The whole battalion went to suppress a revolt against the British in which the Shi’ites and the Sunnis joined together. So here is a British colonial Indian fighting to suppress liberty. Then he has an epiphany. He experiences the harm and the trauma of war, but it’s in a different body. It’s not a U.S. service man, it’s a Punjabi man. Then he meets this Mexican woman. You see what I mean? It’s like, oh, this is crazy!

ERF: Do you feel that this novel you’re writing is a global novel?

HMV: It sort of is but it isn’t, because there are only these little instances, but it’s also pulling together those parallels, it’s interweaving those stories, it’s showing that–at least if I do this right–that we can have an Punjabi man really parallel a U.S. serviceman in the type of haunting that happened during World War II. So he comes back with post-traumatic stress syndrome and all he does is work the fields, and he meets a housekeeper who has just lost her husband, they decide to get married. It’s all because he comes to California, all because of the war, this epiphany about liberation and the fact that he’s not liberated, and yet he’s fighting for the very power that’s colonized him and his people.

ERF: Those parallels are powerful. Especially with undocumented workers and the larger history of human migration. Their stories create parallels to open people’s minds so that they can understand that experiences are connected. The work of empathy is so hard. Aren’t we built to naturally have empathy for each other in order to survive?

HMV: But you know we live in a society that has certain rules, like white is right. These are dominant, patriarchal, and in many ways sexist-enforced rules. I mean how could the U.S. annex the Southwest, where suddenly Mexico becomes the U.S., and citizens lose their land? It was so easy for them. All they said was that you don’t have the legal documents. This is what we do in the U.S.

ERF: Another arbitrary circumstance.

HMV: This sort of greed and manipulation has been throughout the history of the U.S., including with the colonization of the Philippines. The Philippines and the U.S. were allies against the Spanish. And as soon as that happened, they were independent for like two years. And then the U.S. decided they wanted to have them, and that was it. So of course they fought them, but they were no match and so they became possessions of the U.S. Look at Puerto Rico. It’s incredible. There are all these other places that they’ve grabbed for resources.

ERF: Narratives and stories are able to encompass both the historical knowledge and the strange affinities with the different characters. Authors can create moments where people can meet outsiders and understand that identity is something that’s flexible, that can change moment to moment as well.

HMV: As long as you understand your basic cores and principles of who you are. I can see that flexibility, but my basic cores are always about human rights, always speaking up for those who can’t, always recognizing when to speak up and how to do it. I try to do this through my writing. Going back and looking at these parallels, it’s just fascinating. And also, I’m trying to give little history lessons too. I’m trying to create historical narrative that is really dramatic.

ERF: On the reverse, scholars and historians should tell personal stories of the people they study and research as well. Identity is a touchy issue that causes high levels of tension. A lot of the characters you write, such as Ben Brady and Turtle from Their Dogs Came With Them, express the anxiety of walking within multiple identity categories. How do we quiet and calm the anxiety of identity?

HMV: Nobody has the degrees, the historical context, to tell you you’re not someone that you think you are. Nobody has that right. As Malcolm X said, you’re going to call yourself something different than what somebody else calls you. I no longer waste my time when people question my identity, because I know who I am. I know what I stand for. And I know what I work for. I say, Don’t you dare question me on that particular thing. On everything else you can, I’m very open, but not for that.

ERF: I group those people in the same category as those who assume I like spicy food. I have a final question from a student in my class who read The Moths. He writes:

“The symbolism of a moth associated with the death of a family member is relating a very dark, inconceivable moment of pain with the moth’s ability to navigate and survive the dark without ever being recognized for its beauty, much like the grief of death can blind the living from the beautiful moment of passing that ends suffering and anguish. Is the story meant to give the reader the mystical, otherworldly feeling about death (like reincarnation for example) or is it simply meant to help people on this earth understand and cope with death?”

HMV: That is beautiful! I wrote that story when I was 23, 24 years old. It was the only time that I wrote a story in about two weeks. I have never done anything like that again. I’m a constant reviser. The story was in tribute to this pregnant woman who was working in the fields with the sprays, pesticides, and found out that the sprays had deformed her child. I was inspired by a photograph of a Japanese woman who was bathing her badly deformed child. What was so touching to me was the loving gaze that she had for her daughter. And, that the daughter had for the mother. Even though she was really deformed, there was this brilliance of illuminating light. And I said, I want to write about that. That’s what motivated me to end the story in the bathtub. Now that I’m past 60, I’ve had a number of different deaths in the family, some that were tragic, some that I was there for, a part of. I’ve come to realize that in those special moments, there is that imbrication, there is that layering between the living and the dying. It is a very special mystical moment. And I realize that I had written about it forty years earlier with The Moths. I don’t know how many people told me that when they read that, they really grieve for their grandmothers, they grieve for their mothers, they grieve for their children.

ERF: One of my students said the same exact thing. It made him miss and grieve his abuelita. The mystical becomes a real thing that helps a person cope.

HMV: Exactly. And the only time it seems to me, is when you’re helping the dying. You’re being pulled into the death, but at the same time there’s no way you can join them, no matter how much you love this person. There is that imbrication. It’s very powerful and because there was such a sense of love that this story came out of, I got something right about imbrication. And now that I’ve experienced it, I know I got it right.