The Freedom Chat Transcripts: Indian Journalist Sidharth Bhatia

by Olivia Rose Mancing / August 26, 2014 / No comments

The Freedom Chat is an ongoing video series by Sampsonia Way featuring interviews with journalists and other media workers facing censorship and repression in their home countries. In these Q&A’s, conducted via video chat, journalists talk with Sampsonia Way about press freedom, anti-free speech legislation, and exile.

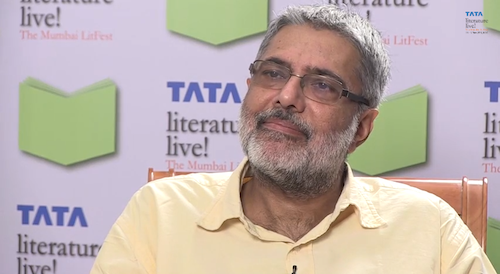

In the ninth installment of The Freedom Chat, editorial intern Olivia Mancing spoke to Sidharth Bhatia, a Mumbai-based writer and columnist who has contributed to several publications, including Times of India and Asian Age.. In this interview he talks about the effect of economic reforms on India’s media, self-censorship, and the future of free speech.

What is the current climate regarding freedom of speech in India?

At the moment there is a gradual but perceptible increase in censorship, not only from the government, but other bodies: religious or community organizations that are trying to clamp down on messages that they don’t agree with.

The most recent example is The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger, a well-known scholar on Hinduism. Although the book was generally praised in India, a group of people objected to the material and took their case to court. While the case was being heard, Penguin decided to pulp the book of their own accord.

Censorship is tricky territory in India. Although publications are not often banned by the government, self-censoring occurs to avoid rejection from publishers due to a pattern of militant reactions from religious groups.

There is also fear that many journalists have been locked out of their jobs because they wrote critiques of the new regime leading up to the election. But by and large, government pressure over the media is now giving way to corporate ownership of Indian media. Today, the real fear is corporate pressure.

In the past two decades, economic liberalization has been reshaping India, creating a Westernized middle class. What did Indian media look like before economic reforms began in 1991 and how would you say its changed since due to economic liberalization?

I’ve been in the profession for about 35 years so I’ve seen different stages of the Indian media’s growth. When I entered the profession, we were in the middle of a national emergency where civil rights were curbed and the press was censored.

When that ended in 1977, Indian media was like a jack-in-the-box. A spring that had been suppressed suddenly burst open. New NGOs were founded and new magazines were published. Investigative journalism grew, and a general consciousness about human rights, and feminism in particular, began to emerge. From 1977 into the 1990s, journalism was at its most robust.

In the midst of the 1991 economic reforms, the clout of the advertiser emerged. Suddenly there were more advertisers pushing more products. At that time newspapers were losing revenue, so they shifted control from the people’s demands to the advertisers that backed them. With the growth of consumerism – a direct result of liberalization – came the growth of corporate sponsorship. In the last seven to ten years, we’ve seen corporate buy-ins of print and television media. This has created massive media organizations that are funded by business interests. The fear is that the advertisers’ control over the media will obscure real news.

There’s a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists that includes India as one of the worst countries for journalists to face murder without repercussion. Via public broadcast, Arvind Kejriwal threatened to jail all media participants who favored his opposition, Modi. How do journalists navigate threats like this?

By and large, journalists working in big cities don’t face direct threats to their physical being. However journalists in rural areas do face threats from groups that they’re investigating.

Because Arvind Kejriwal’s statement was made during a political campaign, it must be taken with a grain of salt. The fear is not that the government or one official is going to personally persecute journalists. The fear is the chilling effect which ownership can sometimes bring. If the ownership of a particular news source is closely affiliated with a political power, that political power can ensure that certain things are not published.

You mention that corporate interests now dictate the media. Have you ever been threatened for something you’ve written?

Occasionally. But, with the exception of a few cases early in my career, I have been fortunate to have never been truly threatened. I worked for various corporate groups and so, when reporting on corruption, the editors would receive calls from the corporate owners telling them what could and could not be written.

Controlling interests ensure that journalists are put in a situation where they have to adhere to corporate messages. These corporate threats to free speech are becoming less subtle. The latest concern is how criticisms of corporate newspapers are being muted and how self-censorship is creeping into the newsroom.

Television reaches far more people than print, and that’s where corporate pressures may heighten most in the coming years. Because of its reach, television can be far more dangerous than newspapers.

While the Indian Constitution ostensibly guarantees freedom of speech, a clause in Article 19 places restrictions on anything that quote, “Threatens the unity, integrity, defense, security, or sovereignty of India, friendly relations with foreign states, or public order.” What does that mean for journalists?

When it comes to “sensitive issues” the laws have never been precise. This leaves room for liberal interpretation of the law in a given instance.

The clause with regard to provocation against community relations is actively used. Its use is threatening to become rampant as community groups are vocalizing their anger over the media’s portrayal of them. Muslim groups have expressed outcry over pieces they felt were written against their prophet and demanded pieces be banned or certain journalists be silenced. Contention between Hindus and Muslims constitutes the greatest use of this clause. Sub-groups within Hindu and Muslim communities further complicate the issue of their representation in the media.

In the early years of my career, groups who expressed concern over an article simply published a letter to the editor. The situation is more complex today, and self-censorship is often resorted to in order to curb violence.

A recent UNICEF report states that the adult literacy rate in India is 62 percent. How does the literacy rate impact the dispersal of written media among Indians?

Literacy rates have been going up. Print media, despite the threats of corporate control, is far more credible than television, and readership is increasing.

What does the future look like for media coverage in India? You said that more and more people are accessing print media. Can we hope to see more independent journalists covering topics outside of corporate interest?

Journalism in India is fairly independent and will continue to be independent. But the worry persists that we may find ourselves in a culture in which corporate influence is heavily extended. Looking toward the future, social media is our strongest asset for maintaining free expression.