Unjuried and Uncensored: An Interview with AS220’s Bert Crenca

by Joshua Barnes / June 12, 2014 / No comments

Umberto “Bert” Crenca is the Artistic Director and Founder of AS220, an artist-run organization committed to providing an unjuried and uncensored forum for the arts in Providence, Rhode Island. Founded in 1985, AS220 offers artists the opportunity to live, work, exhibit, and perform in its facilities, which include rotating gallery spaces, a performance stage, a print shop, a darkroom, live/work studios, and a restaurant, among other things. Its varied and extended list of resources are available to any artist of any discipline for work on almost any project imaginable.

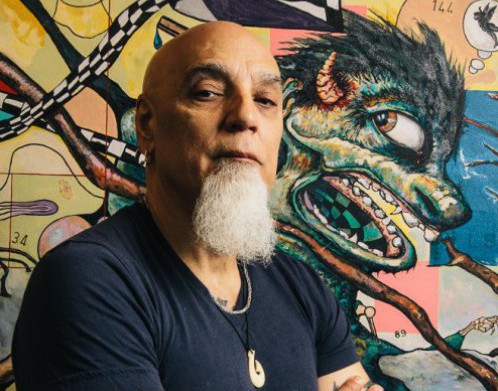

Like AS220 itself, Crenca is a multidisciplinary creature—from visual art, to music, to performance, and, one might argue, business—he has learned to express himself in many different ways. Now in his 60s, he has the energy of someone a third his age and speaks with a brusque, blue-collar flare that highlights his vast knowledge of art, community, and urban development.

In April, Crenca gave a presentation at City of Asylum Pittsburgh on the history of AS220 and how, with just $800, a mission to shake up the art world, and a small group of like-minded artists, his organization helped radically change the face of Providence. In this interview he talks more about that history, the logic behind his $9/hour income, and why he’s personally committed to giving Providence’s at-risk youth an outlet for artistic expression.

Bert, what was the original idea behind founding AS220?

The original idea, back in 1982, was to create an unjuried and uncensored space for visual and performing arts. At the time, a group of local artists and myself were drawn together over criticism of my artwork in the Providence Journal. We started meeting and wrote a manifesto that trashed everything in the art world—all museums, art schools, and foundations, and suggested that artists and their art were not being valued for what they brought to their community, or for reflecting society.

We sent the manifesto out as a press release, it got published and sparked dialogue in the community. People began asking, “How would you run an arts organization differently?” We responded by hosting an unjuried event where anybody and everybody could perform or exhibit their work in 1983. That process formulated the concept of AS220 in my mind.

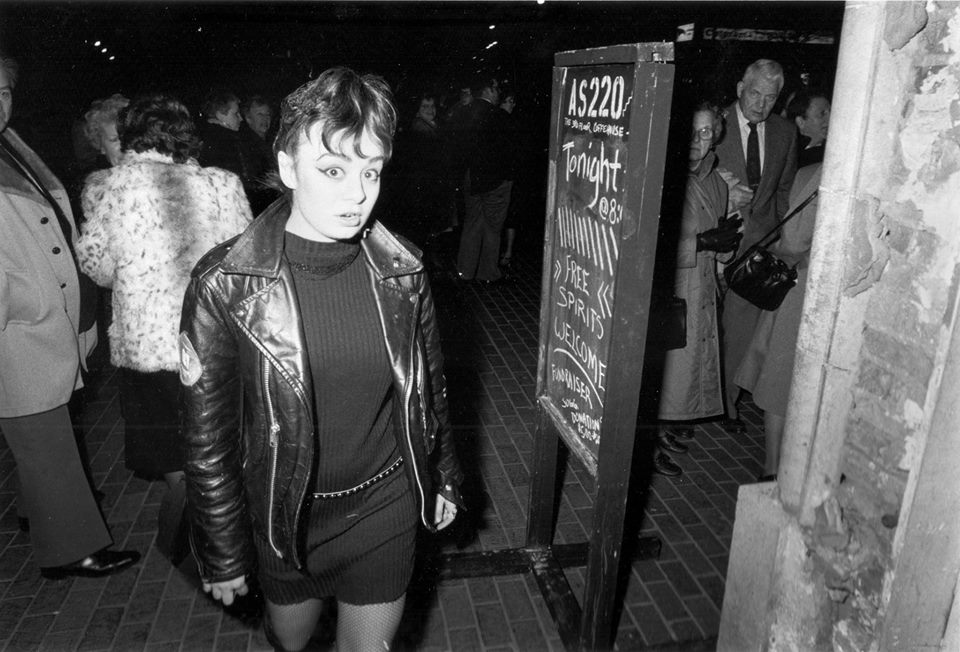

Two years and two trips to Europe later I came back to Providence and wanted to open a place dedicated to the unjuried and uncensored model. I had $800 left to my name and put the money down for the rent on a space. I originally sold them on the idea of a James Taylor-style coffee house, or something with a 1960s feel, but our unrefined mission statement ultimately resulted in the form of all-night raves and crazy metal shows. Within months, we were thrown out of there.

Then we went around the corner to an abandoned building, paid the landlord some rent, and told him not to visit us. That was in 1985. We moved in, we got the water and electric running, and started programming there. We were also living there illegally and through that we learned the value of having a twenty-four hour community in an art space. Thus, we changed our mission to include affordable living and art studios.

When word of AS220 began circulating, touring acts from around the country started coming to Providence. We were having bands like Green Day and famous jazz players like Lee Konitz performing in our illegal loft space. The only requirement was that you either had to have original material, or you had to own the rights. We worked in every genre from hip-hop to monologues, to performance art and poetry slams—anything and everything was welcome. If it hadn’t happened yet, we would encourage it. We later added education to our mission statement when we realized the value of holding workshops, which evolved organically out of that open space.

Twenty-nine years later, we’re a $4 million organization that owns and has renovated three buildings in downtown Providence with 60 employees and all kinds of programming.

Did you experience any kind of opposition in the early days?

A lot of people criticized the fact that anybody could perform or exhibit here. Art has become class-oriented between the popular arts and elite notions of art. AS220 throws those conceptions out the window and replaces them with the notion that everybody is born creative and inquisitive. AS220 aims to provide opportunities for people to fan their flame, and let the audience determine what strikes them.

We also encountered opposition when we first became a 501(c)3 non-profit. When applying for grants, funders would say to us, “How do you ensure quality?” And our response was always that you ensure quality by providing opportunity.

Historically, artists aren’t valued until much later in life, or until after they’ve died. Books are banned, people like Van Gogh sell one painting in their lifetime. In many cases, we’re not very good judges in our own time. That’s why you have to be willing to spotlight things that you may disagree with. There have been people on our stage or our walls whose work I don’t agree with, but their voices need to be heard. For example, we had an artist who used to write broadsides that were very engaging, but incredibly critical of me and AS220. He was very conscious of being a provocateur and said the unjuried mission was bullshit, that there’s always jurying in some way or another because we’re human. We built a space where he could exhibit that work and he became a contributor. I really value his contribution to the development of the organization; he tested us, and me, on a regular basis.

Because of AS220’s unique and successful business model, you’re seen as an expert in the new field of creative placemaking. Is AS220 the flagship of this movement?

We’re just one of many organizations who have realized that providing opportunities for people to develop themselves creatively is good for building strong communities.

People moving back into cities is part of this current phenomenon called creative placemaking, which Richard Florida set a lot in motion when he wrote his book The Rise of the Creative Class, but there’s a lot of people who’ve been doing this kind of creative work for a long time. These days the public is just beginning to catch up and give it a name.

View from upper floor of AS220's Empire Street complex, c. 1993, pre-renovation / occupation. Photo: AS220.

When we first started AS220 in 1985, Providence was in a desperate condition and there was a depletion of people in the city. Since that time, jobs in the creative sector have been on the rise. People are beginning to realize that living isolated lives in the suburbs doesn’t offer the same quality of interaction that common spaces in our cities historically provide. We’re communal by nature and people are trying to find that connection to each other again.

The questions I’m curious about are, how do we want to redefine these common places? What do we want these places to look and feel like? What’s the quality of the experience? Who’s included, and who’s excluded? Are these movements back to cities for people who can afford million-dollar condos, or are there opportunities for everybody to participate and play? The latter is the ideal situation.

AS220 has also been called a “model of sustainability for non-profits.” How does that model work on a practical, day-to-day level?

Our developments are mixed-use, with both commercial and residential tenets, which means we have local businesses and other non-profits that rent from us. We have seven for-profit corporations underneath our non-profit as well. About 60% of our income is earned revenue and the other 40% is contributed through memberships and fundraising events. Our most recent for-profit additions are the restaurant FOO(D), and the bar at AS220. With our board and community restaurateurs we created FOO(D) as a model to serve excellent-quality, affordable local food and beer with a vegetarian/vegan menu. In addition, we use these ventures to give jobs to kids in the community.

Following that, the economics of the organization are unique; all of AS220’s employees are paid the same wage for their work. You make the same amount of money per hour as the crew who paints the gallery walls, or the guy who cleans up after a show. Why do you do that?

When we became a 501(c)3, funders required that we had at least one paid, full-time employee. We wanted to meet the letter of that law, with the least amount of economic impact, so the others started paying me minimum wage for a 40-hour week. Eventually, we all got paid minimum wage, and have slowly tried to bring it up to a living wage with health benefits.

AS220 has always insisted on a horizontal structure. The reason for this is disparities in pay create a dynamic where the head of the company has to behave as though they’re better or more knowledgeable than the other employees to justify their income, and that’s just bullshit. So we all get paid the same, and I’ve always believed that. Look at me—I’m privileged—I’m getting paid to be here in Pittsburgh giving an interview, but somebody has to clean the restaurant and the bar; someone has to book the shows. Is their work any less valuable than mine? Hell no. I’ve done all the jobs at one point or another and I know that the value of our collective work is equal.

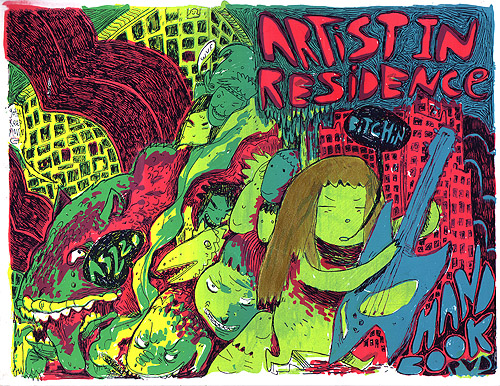

AS220 poster advertising artist residencies. Credit: AS220

That’s one way to create a community of employees. Some of those workers are artists-in-residence at AS220. Do the living spaces also promote an atmosphere of collaboration? Is it easy to maintain a sense of community among the residents?

Our artists-in-residence live in three different arrangements. We have dormitory-style space with a shared kitchen and bath, which is the way we lived together originally; there are also 14 small loft apartments, which are 200 to 400 square feet; and there’s another 22 loft apartments in our mercantile building, which are 800 to 1000 square feet. We put an emphasis on diversity in terms of gender, equity, age, race, ethnicity, discipline, and creative medium—we don’t want 50 singer-songwriters in there, god forbid! We have poets, dancers, sculptors, graphic artists, anything and everything you can imagine. In these spaces collaboration between the artists is inevitable and fairly organic.

Still, anthropology has taught us that communities tend to divide at about two hundred people. That’s very close to the number of artists we have in residence, so we also have to use intentional methods to keep it community-oriented. Thus, every artist is required to do five hours of volunteer service a month for the organization, which can take the form of providing a workshop, or collecting money at the door for a performance, or any number of other things. We also periodically hold Meet-and-Greets for all of the resident artists, which are open to the community, and we hold Open-Houses for artists to check out each others’ studios.

There are over 50 artists living in our buildings who perform, exhibit, and work at AS220. I always joke that we’re going to turn the parking lot next to one of our buildings into a graveyard, so after artists go through the whole cycle of working, exhibiting, teaching, and living at AS220, we can push them out of their window into a hole, and build some beautiful artistic monument to them.

AS220 also provides opportunities to kids in the larger community of Providence, RI through AS220 Youth.

AS220 Youth occupies almost the entire second floor of one of our buildings and has remarkable facilities for the kids to use, including dark rooms, computer labs, paint studios, a recording studio, and a dance studio. However, we primarily do 10 to 12 workshops a week inside a juvenile prison. We also work with at-risk kids through a middle school and teach street kids that find us by word of mouth. Nobody pays us on their behalf. They are only expected to respect the space and everybody in it. With a lot of youth programs that are run by arts organizations, you have to question whether the youth are just visiting the space, or if they do in fact own it. Believe me, they own it at AS220 and they’re very proud of their participation.

What happens when they turn 21 and age out of the youth program?

A lot of the young people we work with are still struggling to find jobs and make the transition into adulthood. Recently, to address that need, we’ve been working to develop more apprenticeship and internship programs between these young adults and the adult population we have. We also want to create some transitional housing for kids coming out of jail. We’ve always got big ideas. Nobody can tell me we can’t do it. We started with nothing, and we’ve done what we’ve done, so I’m gonna think big as long as I’m breathing.

Participants in AS220's Youth Photography program. Credit: AS220

Is AS220 Youth reflexive of your own personal trajectory with the arts?

Absolutely. When I was 18 years old, ex-heroin addicts working through a drug-rehab outreach program intervened in my life. I was never a heroin addict, but I did a lot of other drugs, fought, and gambled. I went to college in 1968, and got a cumulative index of .16. At that time I was caught between the two worlds of being a tough guy because of the neighborhood I came from, and being a hippie because of the women and drugs that came with that crowd.

I was screwing up everything in my life—everything. Eventually I got scared and desperate when heroin started coming onto the scene. I didn’t like what I was seeing. One night I was really high on speed and went into what was once a beatnik-type coffee house. Little did I know, it had been taken over by the drug outreach program I mentioned. I walked in, and people started talking to me, getting inside my head. I started hanging out and got involved there. Those men and women absolutely changed my life and perspective on myself and everything about it. They encouraged me to get involved in art again and mentored me in that process. The rest is history.

When I first met the kids in the juvenile prison, I felt a strong connection to them, fell in love with them, and saw the potential in their stories. It’s just a shame that for the most part, instead of encouraging these kids and providing them with the tools to express themselves through the arts, society hides them behind fences. We don’t want to hear it, we don’t want to be responsible, we don’t want to feel our culpability, because most of the time it’s really social, political, or economic conditions that end up putting them there in the first place. They’re just kids, you know?

Guillermo Gómez Peña's mural at AS220’s Empire Street Complex. Credit: AS220

What would you say to someone who doesn’t believe that art can change a city?

I would ask them, “Then what could, or would?” I’ve explored several different belief systems in my search for meaning and often found religions and political systems to be territorial or violent. The only place where I found peace, where anybody and everybody was welcome across cultural boundaries, where a shared vocabulary was used across all people throughout time, was art. I looked hard and deep to find a place to attach myself to make a difference in this city and found it in the arts.

All art is celebratory, even when it’s deeply critical. The very act of creating art is a celebration, an ode to this mystery called life. Think about the billions of dollars and resources that governments invest into creating things that destroy. A lone artist, with an infinitesimal amount of the same resources, strikes a balance in the world by creating and reinforcing passion.

What advice do you have to offer people or organizations that want to do what you’ve done through AS220?

I have two bits of advice. The first: Show up and do the difficult thing first. Whatever has been distracting you, that you’ve been putting off, is what you should begin your day doing. It’s remarkable how easily the day unfolds and how productive you can be when you do that. The second: Show up on time. Punctuality is important for being perceived as trustworthy and respectable.

To some degree, you also have to be fearless. You have to be able to manage your own self-doubt in the process of getting things done. Understand that every person that you interact with, whether a businessman or a gangster from the hood, has a perspective that you can find value in. You’d be foolish not to want to understand it and utilize it.