The Rainbow Coalition: An Interview with Filmmaker Ray Santisteban

by Joshua Barnes / May 29, 2014 / No comments

Rainbow Coalition (from left): Henry Gaddis, former Black Panther, liaison between Black Panthers and Young Lords; Jose 'Cha Cha' Jimenez, Founder Young Lords Organization; Hy Thurman, Co-Founder, Young Patriots Organization. Photos courtesy of Ray Santisteban.

Ray Santisteban is a Chicano documentary filmmaker and photographer living in San Antonio, Texas. Though Santisteban admits he wasn’t “politically minded, or involved in politics” as a student at New York University in the late 1980s, the focus of his career was honed after he co-produced the documentary Passin It On in 1991. Making this Student Academy award-winning film, which centers on then falsely-imprisoned Black Panther member Dhoruba Bin Wahad, put Santisteban face-to-face with injustice at the hands of the US government and prompted him to start profiling the people that society has left behind.

Sampsonia Way spoke to Santisteban in February about his new documentary-in-progress, which examines the Rainbow Coalition, a short-lived union of Black Panthers, Young Lords, and the Young Patriots Organization who effected change in Chicago’s political hotbed of the late 1960s. Crowdfunded through support from the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures, Rainbow Coalition is the record of an important story that’s only just beginning to gain wider attention. In this interview, Santisteban talks about the roots of disenfranchisement in today’s politics, the FBI’s history of repression, and how a coalition of some of Chicago’s poorest youth-led groups changed the future of national politics in just eight months.

- Ray Santisteban

- Ray Santisteban has produced and directed award winning documentaries that have aired in the U.S. and internationally on public television.

- He has explored subjects as diverse as a one hour documentary on New York Black Panther leader Dhoruba Bin Wahad – Passin’ It On (1993 Student Academy Award winner, documentary category, Co-Producer) and explored the roots of Puerto Rican poetry in, Nuyorican Poets Cafe (1994, Director, Producer, Editor). In 1996, he worked as an associate producer on the four part PBS series ¡CHICANO!: The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement.

- From 1998-2000 he was the director of the San Antonio CineFestival, the nation’s first film and video showcase of Chicano and Latino media. He is currently Directing “Voices From Texas” an hour documentary on poetry and spoken word traditions within the Mexican-American community in Texas and is the Senior Producer on “Visiones: Latino Arts in the United States” a three hour PBS documentary series coming to PBS in 2003.

As a documentary filmmaker you focus primarily on Latino history. Can you talk about why that is?

One of the reasons why I film Latino documentaries is that, in comparison to the African American community, which has been able to tell more of their stories from the 1960s and 70s, the Latino community is about ten or fifteen years behind. I try to tell the often forgotten stories that exist beyond the lives of our national leaders. There’s still a lot of lessons to be learned from the 60s and 70s that folks don’t know about yet.

What kinds of lessons are you talking about?

Politically, we keep repeating the past, but it all comes down to being organized. When you look at the Black Panther Party or the Chicano Movement of the 60s, some of the best organizers were high school dropouts or might have had a limited education. When they got involved in movements and community organizing, they changed. They were able to contribute to their communities in meaningful ways and uplift themselves. Being in a movement taught them how to navigate the political process on both the community- and mainstream political levels. A great example of that from here in San Antonio is Rosie Castro, who was a young political activist in the Chicano Movement of the 1970s. Now one of her sons is Mayor Julian Castro, who was just appointed by President Obama to Secretary of Housing and Urban Development; her other son Joaquín is a congressman. She’s a perfect example of how involvement in movements and community organizing leads to work in mainstream politics.

But today most folks have lost track of the power of movements and community organizing. In the past movements made it easy to participate in politics. You could join the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the Chicano Movement—there were so many. Movements were a way for people to be mentored in community-based politics. Today, without these national movements, it’s much more difficult for folks to participate in politics and to learn how to organize effectively within their communities.

“We’re in a wave where there’s a lot of cynicism about politics… We’re still dealing with the remnants of repression of the 1960s and 70s…”

What do you think is the cause of that disenfranchisement?

We’re in a wave where there’s a lot of cynicism about politics. This is a result of our re-visiting historical movements and grasping the full weight of the government’s push against them. During the 1970s there was FBI involvement, and the Red Squads, but this type of repression carries into the present. We’re still dealing with the remnants of the repression of the 1960s and 70s, and in many ways Government surveillance that was once covert is now almost entirely unconcealed. Every day we learn more about how the NSA has been monitoring our phone calls and everywhere we go there are video cameras recording us, even at stoplights. All of this has a chilling effect on participatory democracy.

Today we need national leaders. Latinos have a tremendous amount of potential political power based on our numbers, but we haven’t utilized it. Who’s the national spokesman for Latino people? We don’t really have one. Though there’s been a pervasive interest and participation in national politics since the last election, I wonder if there’s any one issue that will galvanize people into a national movement? Right now I think that issue is immigration. I make historical documentaries because I’m engaged in these historical stories and see them as a way to engage people in politics, by seeing how grass roots activists have historically achieved much with very little resources through organizing effectively and actively confronting injustices where they saw them.

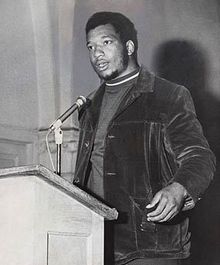

Fred Hampton. Photo: Wikimedia.

You’re currently working on Rainbow Coalition, a documentary about a group of disparate movements in Chicago that banded together for political change in the late 1960s. The Rainbow Coalition is not widely known, though; what was it exactly, and what does the documentary focus on?

Started in Chicago, 1969 by Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, the Rainbow Coalition was comprised of the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords, and the Young Patriots, who were Southern Appalachian whites. Most of these people were about fifteen to eighteen years old—Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez, the founder of the Young Lords, only had an eighth grade education at the time—but they were able to do a lot in Chicago.

These individual movements created clinics, breakfast for children programs, and raised funds for law offices to support people who were being kicked out of their houses. They could’ve had a tremendous effect in Chicago and my story tells the potential of this coalition, which was bi-racial and way ahead of its time. By telling the story of the Rainbow Coalition, I hope to show the potential of this community of people, some of whom were former gang members, or of limited education, who are often forgotten about when people talk about political organizing.

“The Rainbow Coalition went up against Richard J. Daley, one of the most powerful mayors in office, as young people without a lot of resources, some without much formal education…”

The trailer illustrates the positive sense of unity that was fostered by the Rainbow Coalition, but then the coalition is forcibly dismantled and the story concludes on an unsettling note. First, let’s talk about some of the coalition’s positive elements.

It’s not a story with a definitive victory. In some sense, the fact that these people organized to combat urban renewal, police brutality, and poor housing in their communities is a victory in itself. They were combating Chicago’s failing infrastructure and Mayor Richard J. Daley, one of the most infamous mayors in the history of the United States, who oversaw a vast patronage machine which almost entirely excluded people of color. The fact that they went up against one of the most powerful mayors in office as young people without a lot of resources, some without much formal education—that’s already a worthwhile story, no matter how it ends.

The Rainbow Coalition was made up of the poorest groups in Chicago. They weren’t really thought of as a political force in part because they weren’t organized, so the coalition was a useful thing. At the time, the Daley political machine was very powerful. They were co-opting people and communities by giving them stuff, saying, “If you do this, or if you work for me, we’re going to fix this street up.” But the Rainbow Coalition was special because they weren’t asking for political power; what they wanted was political representation, an end to police brutality, better health care services, more jobs, and housing for low income residents, and they couldn’t be bought off. That’s why Mayor Daley took it to the next level, which was getting into police harassment, unlawful surveillance, and ultimately the murder of Fred Hampton, one of the leaders of the Black Panthers.

How did the Rainbow Coalition function while it was active? Was it a fully-integrated group? What were its internal politics like?

The only way to get political power in Chicago was through coalitions, but for the member groups of the Rainbow Coalition unifying factors were economic, not ethnic. For instance, the police at the time were predominately Irish and Polish, which were the old ethnic groups in Chicago. The Irish and the Polish communities had become middle class by the 1960s and hated the Southern whites because they reminded them of what they’d once been. As a result, the police would harass and beat up Southern whites just as badly as members of Puerto Rican and Black communities.

The coalition basically said, “When you need us, we’ll be there for you. If you’re going to do a march, we’ll go to your march. If you’re going to do this action, we’ll be there. If the police come after you, we’ll be there to help you.” Everyone was part of the movement and yet everyone was autonomous. Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez has told me many times that, although Fred Hampton’s Black Panther Party was the largest group in the coalition, Hampton never gave him an order, because the Coalition did not have a leader per se. It was more of a coalition in the sense of, “We’re working toward the same goals. Let’s try to support each others’ movements. Let’s not ignore each other; let’s try to be there for each other.”

“It was bizarre seeing these Southern whites, wearing confederate flags on their hats and jackets, in coalition with the Black Panther Party.”

When I first started production on the film, I would tell people about the coalition and they didn’t believe me; it seemed kind of far-fetched. There were about 10,000 Southern whites in uptown Chicago back in 1969. They recorded their first meetings with The Black Panthers in the coalition, and I saw that footage back in 1991. It was bizarre seeing these Young Patriots wearing confederate flags on their hats and jackets, Southern whites in coalition with the Black Panther Party. One particularly odd situation featured a Black Panther section leader who worked with the Young Patriots named Robert E. Lee III. Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. If I were to just tell people that, they’d just laugh me out of the room.

This sounds like the beginning of a large-scale political movement that could have greatly impacted both Chicago and national politics. How did Mayor Daley respond to the coalition?

The Rainbow Coalition unified several minority movements that were based in different areas across Chicago. This was a political threat to the Mayor, and Daley knew what was happening. Near the end of 1969 the coalition was at a point where, if it had engaged in the nation’s major politics, it would’ve been an affront to the Daley political machine, which was unacceptable in Chicago. At this point the police and the FBI enter the story and start harassing and jailing members of the Rainbow Coalition. It’s a simple formula: If a leader is killed, if members of the organization are being arrested daily and receiving heavy fines, it creates a chilling effect on movements as people become unable to continue organizing due to having to focus on staying out of prison. On December 4, 1969 Fred Hampton was shot and killed in his home by Chicago police. About a month before, supporters of the Young Lords, Reverend Bruce Johnston and his wife Eugenia, were murdered in their home. They were stabbed a total of thirty-five times and that murder has never been solved.

So between Fred Hampton’s announcement of the Rainbow Coalition in May 1969 and his death in December, the movement only lasted about eight months. Did it fully collapse because of his murder or were there people who carried its mission into the future?

There were corresponding movements all across the country during the 1960s and 70s, but all of them were severely disrupted around the same time because of the coordinated political repression that swept in. Many of the Young Lords’ Chicago chapter leadership went underground for a time, and the Young Patriots movement dissolved shortly afterward. The Black Panther Party still existed for several more years, both in Chicago and nationally, but in a greatly diminished capacity. This documentary is about what could have happened had these movements survived, if Hampton had not been murdered. However, despite the murders and police brutality, the Rainbow Coalition served as a model for coalition politics on a national level. For the Latino community, the Coalition helped break down ethnic-based voting patterns. It made Latinos more open to supporting African Americans, who could also represent their interests, which was a big leap. The Young Lords Movement made a huge impact on Chicago. Jose “Cha Cha” Jimenez was an early and vocal supporter of Harold Washington, who was the first black mayor of Chicago. Jimenez helped rally the Latino community behind Washington. Then Barack Obama moved to Chicago because of Washington’s influence; he was looking to learn how to win political office through coalitions, and well, we all know where he is today. Of course there’s also Bobby Rush, the co-founder of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, who has been a congressman for many years now. He went from the Black Panther Party to running for a mainstream political office and is the only person ever to beat Obama in a political contest. Ultimately, the Rainbow Coalition produced some individuals who are incredibly adept in politics and are still working today.

Furthermore, a lot of the issues that the Rainbow Coalition was addressing are still relevant today, particularly in Chicago. Urban renewal, for example, needs to be looked at and approached through a fruitful dialogue, whether that’s through coalition politics, or community organizing, or getting young people involved. But where’s the example? Two years ago, unless you were in Chicago in 1969, you likely wouldn’t even know about this coalition; many people in the towns or cities in which some of the people I’ve interviewed currently live and work may not know that these individuals were nationally known activists at one time. Now there have been some books written about it, and scholarship is getting caught up, but I see this film as a way to get people talking about the history of their communities and understand the sacrifices people made to change the future of multicultural politics.