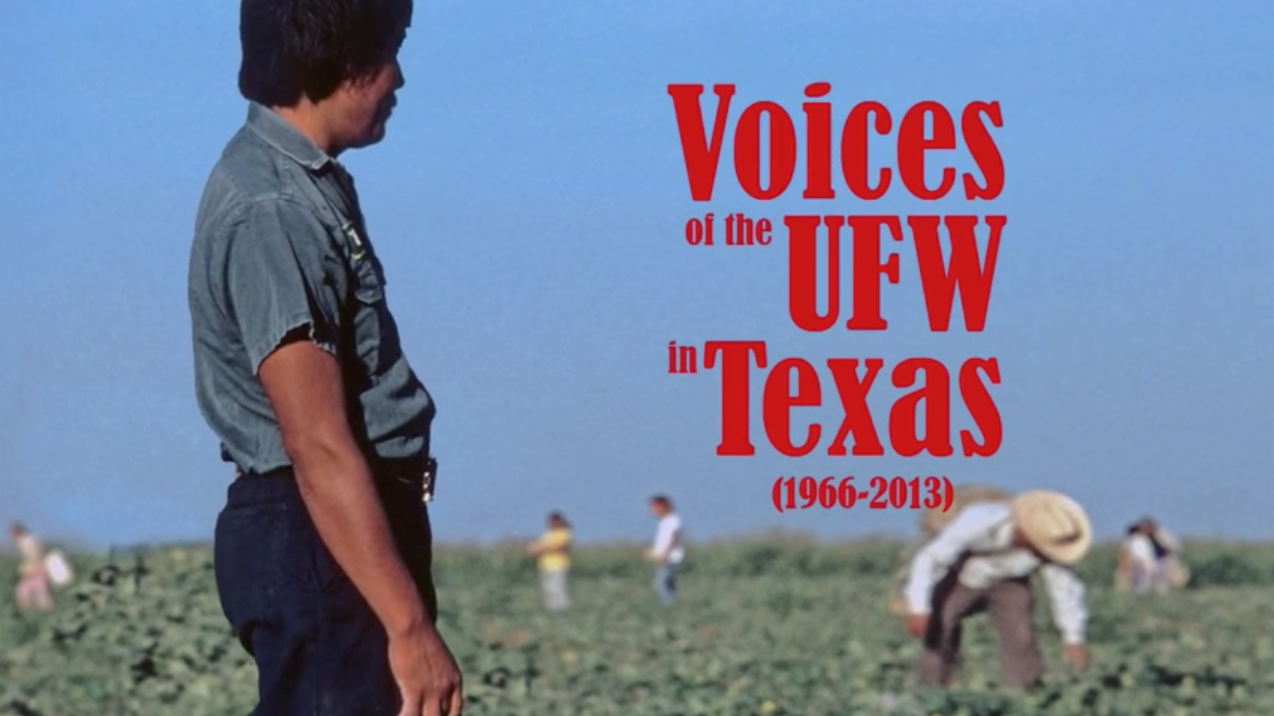

“Voices of the UFW in Texas”: A Documentary on the United Farm Worker Movement in Texas

by Joshua Barnes / April 3, 2014 / 6 Comments

Often crowded, the four-lane Cesar Chavez Boulevard cuts noisily through the middle of San Antonio, Texas. On side streets, murals and posters of Cesar Chavez adorn walls, fences, and storefronts. If you cross the boulevard and head into the city’s predominately Latino Westside, you’ll sometimes see a red flag bearing the crest of the United Farm Workers Movement (UFW) flapping in the breeze. “Si se puede!” the slogan of the movement that Chavez started in the 60s to unionize farm workers and fight for fair treatment, is carefully printed in many places, and scrawled as graffiti almost everywhere else.

All of this would lead you to believe that the legacy of Cesar Chavez and the UFW is still alive and well in Texas. But seven years ago, then graduate student, Crissy Rivas and her mentor, Dr. Raquel Marquez, Sociology Professor at The University of Texas at San Antonio, discovered this wasn’t the case. “There was nothing written about the UFW in Texas,” Rivas says. So they decided they needed to document the movement’s history in Texas, and they needed to do it fast.

“Dr. Marquez had learned that Texas UFW Director, Rebecca Flores, was retiring from her post after 30 years of service to the union,” Rivas explains. “She saw a critical research opportunity to interview all of the farm workers, community leaders, activists, and elected officials that would be in attendance at Rebecca’s retirement celebration.”

Rivas adds, “At first the idea was to catalogue oral histories, but my husband Dave Sims is a filmmaker, so I suggested the possibility of enlisting him, and from there the documentary was born. Even though none of us had ever made a full-length historical documentary, we never looked back. Seven years later, and with the support of many, many people, the documentary is finally complete.”

Voices of the UFW in Texas premiered on March 31—otherwise known as National Cesar Chavez Day—at the original UFW Union hall in San Juan, Texas. Built by the UFW in the early 1970s, the building now headquarters the offices of the UFW offshoot, La Union del Pueblo Entero (LUPE). Made with the support of the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures (NALAC), The University of Texas at San Antonio, and Rebecca Flores, Voices of the UFW in Texas will soon be available on DVD and the team is hopeful it will be distributed digitally in the future.

When I talked to Rivas and Sims in San Antonio on a warm February afternoon, Voices of the UFW in Texas was just entering its final stages of completion. In the following piece they share stories about the unsung heroes of the UFW, the importance of women in the movement, and why the political fight started by Chavez continues in Texas today.

There Was Nothing Written About Farm Workers in Texas

Rivas: The Farm Worker Movement was undoubtedly the impetus for the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. Latino kids in the city saw farm workers rallying and marching and thought, “If these farm workers, these campesinos, can be out here organizing, we’d better get it together.” That’s when urban, university-educated Latino kids started to come together and form the Chicano Civil Rights movement. The farm workers were at it even before the city kids were. So, with this political consciousness, Latinos would go from the fields, to the Farm Workers Movement, to the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, to college, and some eventually made it into the statehouse or any number of elected official positions. That’s a trajectory we see again and again through the movement. There’re a lot of Latino leaders in Texas today because of that trajectory.

But, from an oral history perspective, the history of the UFW is literally dying. During production we lost at least three key participants in the struggle: Erasmo Andrade, Arnold Flores, and Dr. Ramiro Casso. When this project was first conceived, I searched the University of Texas database for books about the United Farm Workers or Cesar Chavez. There were some about California and biographies of Chavez, but there was nothing written about the UFW in Texas. That’s when we realized how important it was to do this research and make this documentary.

Sims: The catalyst for making the documentary was Dr. Marquez coming in contact with Rebecca Flores, who ran the Farm Workers Union from 1975 to 2006. She not only put us in contact with many of the farm workers and organizers, she had also a lot of archival material; her personal collection alone consisted of over 250 photographs.

While it started as an oral history project with the idea to document these stories and flesh out the different perspectives, because of that archive and the people we interviewed who had saved newspaper articles, personal papers, letters that they exchanged with Cesar Chavez, and flyers from events, the documentary is both an oral history and a digital archive. But even with all of that documentation, it wasn’t easy to collect the material we needed. One of the biggest limitations we faced was that people were so poor back in the 1960s and 70s, they had no access to cameras or video.

Rivas: However, we did find some photos that tell powerful stories. One of the first photos I saw was of a worker using a short-handled hoe. They would use these in the fields, hunched over for hours and hours. Eventually the short-handled hoe was banned. That was one of the legislative victories the UFW had. They also eventually secured workers’ compensation and started getting unemployment insurance. But it wasn’t that some politician out of goodwill said, “Let’s ban the short-handled hoe,” or “Let’s give them workers compensation, or unemployment insurance.” Every victory came on the back of a tragic story.

The documentary also explores the brutality farm workers experienced at the hands of the Texas Rangers, once they started fighting for their rights under the union flag. The first strike in Texas was at La Casita Farms in Rio Grande City in 1966. The Texas Rangers came in to break up the striking farm workers and they were rough.

Sims: One person who officially documented these abuses was the late Dr. Casso, a doctor from the Rio Grande Valley who provided medical care to farm workers. He was involved in a lot of big cases against the Texas Rangers, and testified in the Texas Supreme Court, which ended up changing the Rangers’ entire system.

Rivas: The few photos we found from the mid 1960s were partially exposed negatives of Rangers grabbing cameras or trying to rip film out. Eventually, we met a person who was actually there when that stuff was happening with the Rangers.

Sims: The Reverend Ed Krueger. At one point, the Texas Rangers cuffed his hands behind his back and pushed him up next to a moving train, his face inches away from the cars going by. After he told us about this experience, he said, “I didn’t think anybody thought these stories mattered.” This sentiment was shared with us during many of the interviews. These were heroic stories from heroic individuals and it really compelled us to keep moving forward.

House Parties, Pesticides, and Strong Women

Rivas: This documentary wouldn’t have been possible if it wasn’t for Rebecca Flores and her 30 years of dedication to the Union. She grew up in a farm worker family, and, after studying at the University of Michigan, raised her kids through the union, on the picket line, in the union hall, and at the state democratic convention. Some of the most powerful photos we have are of her, sitting at a political convention, holding an infant in one arm, a three-year-old sitting next to her. The strength and the fortitude of all the women in the movement is impressive.

One of the main ways the union organized workers was to host “house parties.” And Fred Ross is credited with conceptualizing this style of meeting, but the Obama campaign also used the technique in 2008 and 2012. Essentially, house parties were events where workers would bring neighbors and friends into their homes. There, a union representative would ask workers about the basic amenities in the fields, like drinking water, toilets, and hand-washing facilities. In that way, among the trusted company of friends, neighbors, and fellow workers, they’d realize, “Hey we don’t even have these basic things.” Through the house parties the Union was able to get the workers to say, “We need to make a change,” and they’d progress from there. Women played a key role in the house parties because the home was the domain of the woman and women were principal in getting people organized in a safe place. There’s no doubt about the impact that Texas women had on the United Farm Worker movement as both organizers and leaders.

Sims: The role of women is a theme of the documentary. The UFW in Texas had mostly female leadership after 1975.

Our History Has to Be Captured and Retold

Rivas: Today, people don’t realize that the original farm workers were citizens, not undocumented immigrants. But as workers started to advocate for their rights they created opportunities for themselves. They got an education, registered as voters, and became middle-class citizens. Consequently, their transition into a better life created a need for undocumented immigrants, because average American citizens don’t want to toil in the fields for 12 hours a day, cutting asparagus or picking potatoes.

(from left) Dr. Raquel R. Marquez, Dave Sims, Rebecca Flores at the premiere of Voices of the UFW in Texas.

Because of this, fifty years later, we’re still fighting. During Rebecca Flores’ tenure as Union leader, the Union’s focus evolved to include legislative activism; the fact that Texas is a right-to-work state makes it difficult for traditional union activities, like boycotts, pickets and strikes, to be effective. Today in Texas there’s a war on women’s rights, and we have to fight to keep religion out of science education, and keep Mexican-American history and historical figures in textbooks. Two years ago the Texas State Board of Education wrote Dolores Huerta, Cesar Chavez’s second-in-command, out of the textbooks. That’s another reason this documentary is important, as an educational tool, to remind people that these farm workers tried to make a difference and that the products of their work are among us everyday. Our history has to be captured and it has to be told and retold and retold.

Sims: The lasting effects of the UFW are the birthing of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, and the upsurge in political activity among Mexican Americans then and today. People just propelled themselves through the social consciousness of the movement into a place of political action to help themselves and others. I think the late Dr. Ramiro Casso said it best: “Service to others is the price that we pay for the privilege of living on this planet.” That’s the legacy of the UFW in Texas, one that we can all be proud of.

6 Comments on "“Voices of the UFW in Texas”: A Documentary on the United Farm Worker Movement in Texas"

I met that gentleman Cesar Chaves in Pittsburgh Pa ,[of all places] & traveled with him for awhile . We came up with a short play & preformed it at his speaking engagements [we never made it to N Side] [68or69]

I am actually delighted to read this webpage posts which contains lots of valuable information, thanks for providing these information.

Hi. I am the Media Librarian for the University of Texas at Austin Libraries and I have a professor who saw you interview article on the documentary film Voices of the UFW In Texas. In the article it mentions that a DVD will be available soon. Do you have a released date or distributor name?

This will be an important film to have in our collection for faculty and student use.

Thank you,

Gary

Hi Gary, Thanks for getting in touch. Crissy Rivas or Dave Sims at UT San Antonio should be able to tell you the status of the film. It might still be in post-production.

Trackbacks for this post