“I Enjoy Correcting Myself”: An Interview with Author Laurent Binet

by Olivia Stransky / March 18, 2014 / 1 Comment

On June 4, 1942, Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Gestapo and one of the most senior leaders of the Third Reich, died in Na Bulovce Hospital, Prague. Called, among other monikers, The Butcher of Prague, The Blond Beast, and Himmler’s Evil Genius, the thirty-eight year old man’s death was the result of Operation Anthropoid, a top-secret assassination plan organized by British Special Operations and carried out by the parachutists Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš. The history of this real-life military thriller is the subject of French writer Laurent Binet’s first novel, HHhH.

Though, in actuality, the book contains two narratives: The story of Heydrich, Gabčík, Kubiš, and the assassination which ultimately killed all of them, is paired with Binet’s personal journey as he researches and analyzes the history he’s reconstructing. Prior to his salon reading at City of Asylum Pittsburgh in November 2013, Binet sat down to discuss the dangers of mixing history and fiction, why narrators are unnecessary, and the vulgarity of fictional characters.

Would you be bothered if someone described HHhH as a personal essay rather than historical fiction?

There’s definitely a story in the book that talks about why “essay” might be a limiting description, but no, I wouldn’t mind. I mind more when people say it’s fiction because it’s not. It’s both a true story and an essay about how fiction can work with history. Fiction mixing with history is very complicated, which is what I wanted to show in HHhH. That’s why I obsessively point out the fictional parts, which make up maybe 15% of the book. You can call it a personal essay; I’m okay with that, but not fiction.

What would you call your book instead of “historical fiction?”

I would say “historical novel” instead of “historical fiction.” The way my book works is similar to Maus by Art Spiegelman. In Maus there’s the story of the father during the 1940s and the meta-novel dimension where you can see Art Spiegelman interview his father and try to rebuild his father’s story. What I did isn’t very different, except I didn’t deal with living witnesses. I wish I could have, but they were all dead, so I had to work with books, research, and places. But it’s the same system: The story and the investigation needed to tell the story.

How would you respond to critics who say that they came to read about Reinhard Heydrich’s killers and assassination, not about your personal thoughts?

I understand. It’s totally their right to be disappointed or feel cheated. But the story of the assassination is in the book. If you skip all my comments, that’s what will be left, hopefully full of suspense. That part is a page-turner, but I’m not really interested in a novel that’s just a story. I think to be interesting, a novel also has to be a meta-novel. I would be disappointed if I read a book that was just a story and nothing more. I like a novel to be both a story and a conversation between the author and the reader.

Due to the way you correct yourself in the book, an unthinking reader might believe your book is unedited. What do you say to that?

For me, as a reader, what’s interesting is not only the final result, but also the demonstration of how the writer got to that final result. I wrote my novel in this way so that I could share my ideas, even the wrong ones—which I then explain are wrong—with my readers. At one point I write that the code-name of the chief of the secret services was H, which I liked because it sounded like something from James Bond. But then I discovered it was not H, but C, which was not as funny. I corrected myself, but I didn’t erase that bit because I liked discussing James Bond at that point. I enjoy correcting myself.

You’ve mentioned before that you hate having to make a distinction between author and narrator. Why is that?

The distinction between author and narrator is usually artificial, or not very relevant. In many books the narrator is not the author, but I think it’s useless to invent a narrator who’s just a mouthpiece for the author. The problem is, at least in France, many people believe that it’s a code for literature: If you don’t have a narrator you aren’t writing literature. Writers believe that they have to invent a narrator even if it doesn’t add anything to the story. It’s better, in my case and in many other cases, to just skip that whole operation.

Do you believe it’s really possible for this kind of historical novel to be objective?

No, it’s not. The point isn’t to be objective; that’s not possible. The point is to not feign objectivity. That’s one reason why I appear in the book: I don’t want the reader to believe that what I say is the absolute truth. I tried to be as honest as I could with the facts, but when I give my opinion I want the reader to know who’s talking to them. In my book, I show that I am a Frenchman, a teacher; I am connected with Slovakia because I live there. I also love Prague, so that’s why I can be upset about the Munich Agreement.

When I read the finished book I was surprised to discover that I was very hard on Édouard Daladier and Neville Chamberlain, the French and English Prime Ministers at the time. I felt betrayed by them because they betrayed Czechoslovakia. I was not being very objective, but at least a reader knows why I’m not objective. The point is to show that there is no objectivity, to show from what point of view I am talking to you.

On one of the first pages of HHhH, you say that nothing could be more vulgar than an invented character. What about The Brothers Karamazov? Is Dostoyevsky’s creation vulgar?

Sometimes it’s useless to invent characters when history configures real people that are interesting enough. Of course, there are many fictional characters I love that are very important in my life, but I started with that provocation just to stress the point that I’m writing about a true story with real people.

It’s funny that you mention Dostoyevsky, because the French surrealist writers influenced me. In HHhH I mention André Breton’s Manifeste du surréalism (Surrealist Manifesto), when he quotes Paul Valéry: “I could never write ‘The Marquise went out at five o’clock.’” Valéry thought it was childish to speak about an invented character and give her an artificial life. Breton then quotes a description of an invented room. He says that as he knows the room is fictional he’s not interested in reading about it. Then you discover that passage is actually from Crime and Punishment by Dostoyevsky. I love the provocation and arrogance of the surrealist writers. They were not afraid to attack big authors like Dostoyevsky.

In previous interviews, you’ve stated that you are more interested in American and English writers than French writers. What are the biggest differences between English and American writing and French writing right now?

Most French writers are not very interested in form, in what makes a novel. They just use the novel as a template to tell a story and are more interested in themes. But literature is all a question of form. These French authors write novels like the ones you’d read from one or two centuries ago. What was interesting two centuries ago is not interesting anymore. I’ve said before that French writers believe they have to write like Balzac. That’s their mistake. There are interesting French writers, but on the whole, American and English writers are more playful. They are more creative. They know that a modern novel has to be in some way a meta-novel too. They’re funny and not as arrogant as French writers.

Who do you consider to be a great fiction writer?

I am not fond of realistic, psychological novels. When you make up a story, it has to be more than reality. If it looks like reality, then just talk about reality. Kafka’s world is amazing and characters like Josef K in The Trial or K in The Castle are wonderful.

As a writer I am full of contradictions, and I am very impressed by the Russian writers’ characters, like Prince Andrei Bolkonsky and Countess Natasha Rostova from War and Peace. Most of the time, I’m more interested by extraordinary stories. The boy in The Catcher in the Rye is amazing and I don’t consider that work realism. The Catcher in the Rye is almost a fairy-tale. I’m also fond of Bret Easton Ellis’ work; his characters are insane and extraordinary.

As a writer have you faced any limits on your free expression?

I wish I could say I haven’t, but that’s not true. While I was writing HHhH, the 2007 presidential campaign in France happened, and the platform of future president Nicolas Sarkozy reminded me of the 1930s in Germany. I made a digression in my book to compare Nicolas Sarkozy’s social program with some things from the Nazis. For instance, I heard Sarkozy say that “working is freedom,” which reminded me of “Arbeit macht frei” (“Working makes you free”), the phrase that appeared over the gates of concentration camps. Later my publisher told me I couldn’t say that. Apparently, there is a limit.

After HHhH, I wrote Rien ne se passe comme prévu, a book about the 2012 French presidential elections, following candidate François Hollande. He allowed me to follow him and write anything I wanted. But in the end, I started wondering if I really could write anything I wanted because Hollande had given me his trust, and I didn’t want to betray that. At the same time I wanted to report what I had seen. I may have censored myself on some occasions and not on others. It was really case-by-case.

What is your relationship with your editors? How much do you allow them to change?

It depends. For HHhH I had to concede a lot, but I was fighting to defend my point of view. It’s very difficult to get the right balance. You have to keep in mind that your editor is not your enemy, but you also have to trust and believe in yourself. It’s necessary to read your work as though it were not your own, and the editor can help with that, but at some point you have to decide who’s right. It’s a complicated process.

Originally you wanted the title of the book to be Operation Anthropoid.

Yes, because that was the name of the covert operation to assassinate Heydrich. For the ten years I was writing I called the book Operation Anthropoid, so it was a big disappointment when the name was changed. My publisher told me that Operation Anthropoid sounded like a sci-fi novel. I was really disappointed, but he earned my trust when he suggested HHhH. It comes from a joke among the S.S. that “Himmler’s brain is called Heydrich,” which in German is “Himmlers Hirn heisst Heydrich.” Suggesting this title proved that my publisher had read the book carefully because I only mentioned that joke briefly. Though it took me weeks to decide if I agreed with that title, I’m happy with it now.

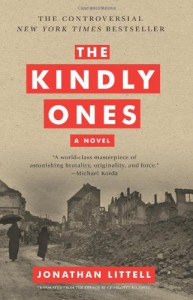

There were also sections of the book that were cut out, the ones regarding Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones.

When I read The Kindly Ones, I was a bit obsessed with it. Almost every day, I wrote a chapter about what I had read. At some point, my book became the diary of The Kindly Ones, so the editor was right to cut those sections. He let me retain enough to get my point across, and actually, one sentence that survived became the most quoted part of the book in France, “Houellebecq does Nazism.” The cut part was later translated and published on an American site called The Millions. Those excerpts are now available in English but not in French.

If you were going to write another historical novel, who would it be about?

My next novel will be somewhat historical since it takes places in the 1980s. But my publisher would kill me if I told you who it’s about.

Can you tell me anything about the next book?

Like HHhH it will be about the complex relationship between reality and fiction. This time it will be more playful, and the results should be very different.

One Comment on "“I Enjoy Correcting Myself”: An Interview with Author Laurent Binet"

Recently I had opportunity to read HHhH book n slovenian edition. The book is wanderfull because author succesfuly combined his personal considerations with available short known or written informations. The book is readable