Interview with Tienchi Martin-Liao, Independent Chinese PEN Centre President

by Silvia Duarte / May 20, 2013 / No comments

When Enemies and Hatred are Inevitable

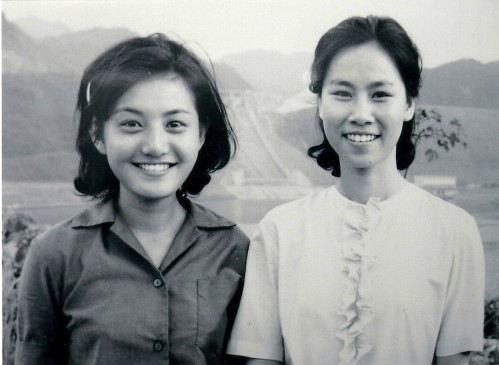

Tienchi Martin-Liao (right) when she was in college at National Taiwan Univerisity in 1968. She is now the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre. Photo courtesy of Tienchi Martin-Liao.

Depending upon who you ask about Tienchi Martin-Liao’s expertise, you could get many different answers. Readers and defenders of literature may recognize her as the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre; German intellectual circles would define her as the scholar who has translated Chinese fiction, poetry, and essays into their language. If he could speak freely, Nobel Peace Prize-winner Liu Xiaobo would refer to her as a friend; the celebrated writer Liao Yiwu might say she was one of the first to promote his writing in the West; and the Nobel Prize in Literature-winner Mo Yan may rebuke her for questioning his lukewarm posture on Government censorship. For her solidarity, many Chinese writers appreciate her when and after they face persecution; some Chinese readers would see her as the writer who wakes them up with provocative headlines in Hong Kong and Taiwanese newspapers. Additionally, Sampsonia Way celebrates her as one of its main writers.

Of course, if you ask the Chinese Government, they could list her as a persona non grata for her work against their Labor Reform, for her promotion of dissident writers, and for her broad recognition in the West. In this interview Tienchi talks about all the roles she has had through her varied career and their personal consequences, including her enemies and hatred.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

You studied English and American literature at the National Taiwan University. What was your perspective on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) at that time?

We had a very limited knowledge about the PRC. I was at the university from 1965 to 1969, when the Cultural Revolution had a massive impact. In Taiwan we didn’t really have uncensored news or reports about China, so we read lots of horrible headlines and statements like “Dead bodies are floating down the river to Hong Kong” or “There are people from China trying to swim across the sea to reach Hong Kong.” But I didn’t believe all these stories we read in the newspaper, I always thought they were exaggerations.

Now that you are the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, has anybody accused you of having a biased perspective, because you are from Taiwan?

A huge period of time passed between my being a student in Taipei and my being the president of PEN China. All that I have done in between has given me the necessary knowledge and credibility to represent this institution. People focus on my expertise and not on my nationality.

Also, through my work in literature and the university, I have lots of friends inside the PRC. My main Chinese PEN circle consists of people from China, not from Taiwan.

I would like to talk about the period of time in between those two points. There are many job positions listed in your byline but, as with any other byline, it tends to hide your experiences, fights, challenges, and successes. So let’s start with why you moved to Germany in the 1970s?

The only reason I moved to Germany is because I married a German sinologist after I graduated from the university. Otherwise I would be in the US, where most of my college classmates are now.

During that period you worked at the Institute of Asian Affairs in Hamburg. Could you talk about the Chinese-German dictionary you worked on and your research on Mao Zedong’s writing?

For three years I worked with other three colleagues to compile the German-Chinese dictionary Deutsch-Chinesischer Wortschatz, Politik und Wirtschaft. It is a dictionary of political terminologies. It was published for Langenscheidt, one of the biggest dictionary publishing houses. After that I started to compile the works of Mao Zedong with a group of other scholars. We focused on his works after 1949, because there was already too much information from before. We published seven volumes of Mao Zedong’s works. It was a huge project.

At that time I thought that the Cultural Revolution could build a new society with fairness and equality.

What surprised you the most about Mao Zedong when working on that project?

This is a good question because it had an impact on my intellectual orientation and also on my political mindset. I came to Germany 1971, after the student protests of 1968, when there was still enthusiasm for leftist projects. So I had an illusion about what was happening in China. At that time I thought that the Cultural Revolution could build a new society with fairness and equality.

Then we started the dictionary project, and I had to read lots of newspapers and magazines, which is why I started to wake up. When we worked on Mao Zedong’s Collected Work [Hanser Verlag, Munich 1976-1980] I read what Mao had written, his speeches and other information about his government. It was then that I started to understand what really happened in the 50s and 60s in China. I was shocked to discover that you could be arrested, and even killed, if you wrote one wrong sentence.

Can we say that discovering this lack of freedom of speech was a turning point to do what you are doing now: Defending those who dare to speak their minds?

Well, this was just part of it. The next step was in the 80s, when I read the literature from China that emerged in the late 1970s, soon after the death of Mao Zedong. It was called “Scar literature” or “literature of the wounded.” It exposed horrible things about all the political campaigns in the 50s and the Cultural Revolution in the 60s and the rule of the Gang of Four in the 70s.

Even though this genre isn’t considered high literature, it’s still great material for understanding that time. It’s really personal. It will describe, for instance, how a young man or woman who got involved in the political campaigns faced the most terrible fate and lost everything, including their faith and illusions. This literature came from the lost generation, which includes millions of young Chinese who believed in the Cultural Revolution’s ideas and then discovered that they were cheated. All this shocked me a lot, much more than Mao’s work.

So it seems you were becoming more and more political through history and literature. Were both disciplines decisive in the role you had after the Tiananmen Square massacre?

Yes. I couldn’t help but to get involved in this democratic movement, and so step by step I got deeply involved with China’s politics too.

In the early 90s you also worked for the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation and became well known in that field. What exactly did you do during that time?

I started this translation center with the help of my husband, who was a professor. We focused on two things: We created a library of translated work which spans from traditional to contemporary literature from the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. Then we published a series of 22 volumes of Chinese-German literary translations called Arcus Chinatext. We included poetry, fiction, and essays.

And then you came to Washington, D.C. and became the director of the Laogai Research Foundation. What is the main goal of this organization?

In 1992, the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) was established to gather information and to educate the public about the Laogai. Lao means labor. Gai means reform. The Laogai, China’s brutal system of labor camps, remains one of the most glaring blemishes on the country’s human rights record. Although the term Laogai (reform through labor) was replaced in official use with jianyu (prison) in 1994, the true nature of the Laogai has not changed. The Laogai slogan “Reform first, production second,” continues to appear on prison gates and millions of Laogai prisoners continue to endure “reform” exercises that entail forced labor, political indoctrination, and often, physical and mental abuse.

The Laogai, China’s brutal system of labor camps, remains one of the most glaring blemishes on the country’s human rights record.

You were responsible for the The Laogai Handbook, now in its 10th edition, which covers the most extensive and covert network of forced labor camps in the world. Why is that handbook so important?

It’s important as an academic source, but also because it makes us think of the men and women who are suffering in the Laogai today. Only the attention of the world can bring about an end to that suffering.

We don’t use the word concentration camp, but of course these labor camps in China are a bit similar. We put together material from all these camps, and for each we detailed the location, population, and structure. Some of these camps are also factories, so we describe what kind of factory each prison is and what kind of products they make. We update it every two years.

Being in the Laogai Research Foundation, you have also worked on the Black Series, a collection of autobiographies of political prisoners who have survived the Laogai camps. This series provides a sharp contrast to China’s nationalistic government-sponsored publications. What is the process of publishing this material like?

Ninety percent of these publications are autobiographies. People contact us and send us their manuscripts, I read them and make a decision on whether we´ll publish them or not. After I edit each piece I send it back to the author, and he or she has to approve it and send it back. After we published three or four books, we started getting more and more manuscripts.

Have some of these authors suffered persecution for the publications?

Not all. About half of the authors are still living inside China, and the other half have already left the country. Those who are still living in China have not necessarily been persecuted, but they have been warned by the authorities.

We had troubles with one particular book about the campaign of persecution of intellectuals that started in 1957. Young people were sent to Singhai province, or other very remote places. A group of 3,000 intellectuals was sent to Gangsu province, in the Northwest, and when the great famine struck China, only around 500 survived. The author of this book interviewed the survivors. When we published it, the authorities threatened him and forbade him to have contact with us. They warned us to not send him copies of the book. I tried to smuggle the book into China, but it was very dangerous.

I tried to smuggle the book into China, but it was very dangerous.

These books can’t be distributed in China, right?

No, they can’t. We distributed them through a bookstore in Hong Kong and through the LRF online bookstore. Sometimes people inside China can buy them online.

In terms of credibility, what are the risks of publishing autobiographies?

Well, not everyone is totally honest when writing their own stories, and the authors are not real writers. They just survived and wrote their stories. Still, this is very valuable material for understanding what happens in China.

Who is the most well-known author in the series?

Liao Yiwu. We have published four of his books. Maybe it’s not humble to say, but I was one of the first people who promoted his work. He doesn’t need my promotion anymore.

Another fact that has marked your life is your professional relationship with the Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. How did you meet?

I’ve known Liu Xiaobo since 2001, when I started to work in the United States. He was inside China and wrote for two websites I ran at that time. I often spoke with him via Skype or telephone. He’d send me his articles and I’d read them fast—within five minutes—and post them on our website, with him still on the phone.

Sometimes he would give me his article or some information and he wouldn’t hang up, so I could hear him smoking or his wife, Liu Xia, bringing him soup and he’d make slurping sounds. It was very funny, and I really felt like part of their private life. Although we never met in person, we felt that we were close friends. Of course I’m not the only one; he has lots of friends.

In 2005, before he was arrested, he gave you his manuscript for Civil Awakening- The Dawn of a Free China, right?

Yes. It compiles his thoughts and analysis of Chinese politics, society, literature, and cultural life. I edited it and published it in Chinese for the Laogai Research Foundation. It’s a very good book, and Liu Xiaobo himself told me it’s one of his favorites.

You’re still really involved with Liu Xia and Liu Xiaobo even though you don’t have access to them. Can you explain how?

After Liu Xiaobo was arrested, I contacted Liu Xia and tried to give her some connections and show my solidarity, both personally and institutionally. After Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Liu Xia asked me to take care of his copyrights. In 2012 I published No Enemies, No Hatred.

Can you describe him as writer and as a person?

He is a wonderful writer, so sharp. He makes such good observations of society, of what is happening and the cause and effect of certain things. He is very courageous. He used to be the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, and you know these kinds of small organizations always have fights and disagreements. That´s why I can say he is a good negotiator too. He is very funny and very fast.

When you were on Skype or on the phone with him, did you ever find yourselves under surveillance?

When Liu Xiaobo was the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, I was on the board, and every other week we had a board meeting. The conference was through Google Talk, and very often the connection was interrupted. During the meeting he would say “Oh I lost connection,” and he just hung up, so somebody else had to pick up his position and chair the conference.

This is the new tendency from the government. They incarcerate or disappear the men and then persecute and harass the family, especially the wife, to scare their children.

After Liu Xiaobo was arrested, Liu Xia was under house arrest. Persecuting and harassing the families of political prisoners has become a common practice for the Chinese government. In Blind Chess, your column in Sampsonia Way, you recently told the story of Anni, the 10-year-old daughter of an activist, who has been harassed at school. Can you tell me more about this practice?

This is the new tendency from the government. They incarcerate or disappear the men and then persecute and harass the family, especially the wife, to scare their children.

During the Jasmine Revolution, one of our PEN members was kept under custody. The police used to come to his 30-year-old wife’s house and say: “We have to stay with you.” All day they drank their tea in her kitchen, sat on her sofa, and watched her. They could also take the prisoner’s wife to the police station and keep her there for hours and hours, sometimes days. Or they would freeze her bank account so she had no money.

Anni is one of the extreme examples. People are really furious about it, and I think that’s going to show the government that they cannot deprive a child of her right to education. Hers is a special case.

Now that you are the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, what are the three biggest challenges you face?

The biggest challenge I face is that some our members are always endangered, so I’m constantly worried about it. During the Jasmine Revolution massive amounts of people disappeared, and that worried me a lot.

How you deal with the anguish?

The only thing I can do is contact families and comfort and encourage them. We also speak out and raise international attention and ask for help from other organizations to co-sign appeals.

Which has been the most painful experience related with a PEN member?

It was on December 31, 2010. One of our imprisoned members died; but right before he died they threw him out of prison. He was taken to the emergency room and died there. His case is a typical example of literary inquisition. He was sentenced to six years and suffered until he died just because he had written some articles. Cases like his are real nightmare for us, especially for me, because I’m left with the feeling that we haven’t done enough.

What other challenges do you face as the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre?

The second is that we want to promote more literature in China, and that is difficult. Our members cannot get together or have a panel. When we have our annual conference in Hong Kong, most of our members are not allowed to cross the border. Still, we give them a space on our PEN website where they can publish their work, and we have tried to collect funding to publish more books on the site, but we could only publish a chronicle of victims of the literary inquisition over the past sixty years. It’s a very good book that we are trying to translate into English.

The third challenge is to provide our members with international connections. I try to invite our members in China to international conferences or find scholarships for them. I invite them to come to Europe to stay for a couple of months and give them the opportunity to open their eyes and see what the world looks like. Unfortunately I have no influence in the US.

Have you ever censored yourself?

Living in Europe or the United States it’s not necessary. We, who are living abroad, enjoy this freedom, and I think it’s really important to speak out and not be too self-centered. We have to be humble, but we have to be honest. We have to depend on somewhat reliable information and do our analysis and try to understand the real China and write it down and introduce it to Western readers.

Tienchi Martin-Liao meets with the Dalai Lama in Dharmasala, India this year. Photo: Courtesy of the author.

Is this need to speak out the reason you were one of the first to write with a sharp pen when Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize?

Yes. We need to see this Nobel Prize from two sides. One side is the literary quality. If you look at those who have been prize winners in the past, you can think that Mo Yan is not that bad. He’s okay. The other side is his position on censorship, which brings up a lot of questions about his views on human rights. As the vice president of the official Chinese PEN, he has done several things to show his loyalty to the party, and this is what I cannot endure. Maybe some people say, “Who cares?” but I do care!

I don’t have fear, but I do have hatred, I do have enemies. I hate this oppression, and I hate the system, and the system is made by people.

Don’t you fear persecution?

I don’t have fear, but I do have hatred, I do have enemies. I hate this oppression, and I hate the system, and the system is made by people. I hate those who deprive my colleagues and friends their freedom of expression and basic human rights. I not only hate them, I try to fight against them. But as for my person, I really don’t have any fear.

You also don’t have family inside the mainland.

No, not really. I don’t have to worry about anyone in China. So this gives me a lot of freedom. It really is a privilege. Some of my friends still have family in China, so you are right to mention this. However I don’t think these friends censor themselves either. If you’re honest you won’t do any self-censorship.

But isn’t it still dangerous?

No. I’m not especially courageous, I just have a clear mind, and I know how repression works in China. I don’t think they will harm a person like me, living in the West. It isn’t worthwhile.

I will never do something too dangerous, like set fire to the Chinese embassy or cross the border with the wrong passport. I do very reasonable things, and if I get rejected, I accept it, but I always try.

Again, I’m not especially brave; the ones who are really brave are our PEN members living inside China. I learn a lot from them. Every year they come to Hong Kong to participate in our conference, and I am always very moved by their courage because they have to fight against the authorities who want to stop them from attending. They deal with the security police and go to the border, are stopped, and try and try again. Then suddenly they are sitting in front of me in a conference room, and I am moved to tears to see them all. They are courageous, not me.

We tend to be more emotionally vulnerable when the threats or repercussions target the ones we love or admire than when they target us. How do you deal with that vulnerability?

The situation is not always so critical. Liu Xiaobo’s sentence, his Nobel Prize, and the Jasmine Revolution were critical times, and I worried about our people. And if I talked to them I told them, “Please be patient. This is a very dangerous time. Please don’t get too naughty, don’t annoy the police. Maybe you could stop writing for a month.” I really said that. I asked them not to write because I was afraid they’d get in trouble. But the situation has changed for the better. The people inside don’t agree with me; they say it’s still as bad, but I believe it’s not that awful at the moment.

What will change with the new government?

There are different opinions. One opinion, which I find convincing, is that we have to give the new government a little more time. Even though it’s already been in power for six months, we have to wait until autumn or winter to make a judgment. It will depend on what kind of crises they have to face. If there is a crisis in the summer then they can become very strict in the following months, but if not, they will try small changes. They have the will to make some changes, I believe.

Will we see changes related with censorship?

No, I don’t think they will change that. But sometimes the market controls more than the government. There are some market demands: People want to read certain things so people will write those things. You can already see lots of bloggers, and Facebook and Twitter users, who the government cannot control. All these things are striking at censorship. Maybe they will loosen a little bit—not because they want to, but because they can’t control everything anymore. The only reason they’d change is because the situation is forcing them to do so.