Censorship Behind the Iron Curtain and Its Parallels Today

by Olivia Stransky / January 23, 2013 / 1 Comment

An Anne Applebaum Interview

Anne Applebaum (left) moderating a panel on 'Women for Democracy.' Photo: PolandMFA, Creative Commons.

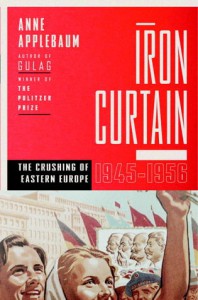

Anne Applebaum is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and journalist for The Washington Post and Slate. Her newest book, Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956, was published in October 2012 by Allen Lane (UK) and Doubleday (US) and was a finalist for the National Book Award for Nonfiction. Iron Curtain focuses on three countries, Poland, Hungary, and East Germany, and examines how the Soviet Union implemented totalitarian control over them following the social, cultural, and technological devastation caused by World War II.

Though the Soviet Union hasn’t existed for twenty years, Applebaum’s focus on the “how-to” of totalitarianism keeps the book relevant. The world continues to deal with different levels of control over the media and repression, whether it is in North Korea, China, or the United States. In this interview with Sampsonia Way, Applebaum discusses free speech and totalitarianism, the effect of social media on government control, and how Communist Poland negotiated its own transition to democracy.

I was hoping you could explain to our readers how World War II enabled the Soviet Union to stage such an effective takeover of the media in the Eastern Bloc countries.

World War II devastated all of the existing media in the region. The Nazi occupiers had either taken over or destroyed newspapers, magazines, and radio. In some cases, radio broadcasting equipment no longer existed. In Poland, where all the transmitters had been destroyed or stolen during the war, the Soviet Union provided new transmitters and physically recreated the radio. In Germany, they occupied existing broadcasters and brought in new managers and reporters. The postwar vacuum was very easy to fill in the short term.

In Iron Curtain you talk a little about Communist radio stations having to deal with the cultural expectations of their listeners. To what extent did propaganda have to adapt to the various countries it was used in?

Eventually radio stations adapted to local conditions because the people who were doing the programming were local, and they had to reflect local interests and local ways of doing things. The Moscow-trained communists, who in some cases arrived to help direct the stations, had a different agenda, of course. But although they changed broadcasters and altered programs, inevitably the rest of the staff, the technical people and ordinary journalists, some of whom had been there before the war, remained in place.

In the chapter called “Radio” you talk about a radio station in East Germany having to deal with complaints and expectations from its audience. They even had a question and answer segment. But can we say that this radio station was effective?

I’m not sure if the communist-run radio was ever effective. While reading the archives, it became clear to me that the people who ran these radio stations were always conscious of their own failings. They worried quite a lot about being boring. They knew on some level that people weren’t listening to them, or were listening to the music but not to the speeches. They argued all the time about how to become more relevant. In the East German radio archives I found a wonderful document which records an argument between the station managers about Communist Party leader Walter Ulbricht’s speeches. One of them said, “Well his speeches are very boring. Maybe we could cut them and thereby draw more people in.” Another one says, “No, we can’t do that, we might be cutting out something important. The point is that people learn to understand these speeches, we must teach them to understand these speeches.”

The people who ran the radio stations worried all the time about whether they were reaching people and whether the propaganda was working. They certainly had evidence that it was not, including, as noted, from the letters that people wrote to the radio stations.

Was there any medium available to dissenters inside these countries?

During the period my book describes, there really isn’t any dissident writing or dissident media. In the very beginning there were still a few independent newspapers, which managed to get paper from the government and to print articles critical of the communist party. But after 1947 or 1948, there really isn’t anything. Effectively, in this part of the world, there wasn’t any dissident media until the underground press began to develop in the 1970s.

There are a few exceptions of course. In October 1956, during the uprising in Hungary, Hungarian radio became very independent. During the 1956 strikes in Poland, the official media became freer there, too, though in both cases that freedom was eventually reversed. But, for the most part, there was nothing that we would recognize as opposition papers or radio in the forties and sixties.

Is the censorship that happened then even possible today, because of the existence of social media?

It’s harder, given the internet and social media, although authoritarian regimes are learning how to control the internet, too. I would not underestimate the ability of the Chinese or the Iranian or the Russian governments to exert control over social media and electronic media. We assume at the moment that these are naturally dissident forms of communication, but that’s not necessarily going to be true forever.

In terms of censorship and the press used as a propaganda tool: Do you see similarities between what happened from 1945 to 1956 and what is happening today in countries like Cuba or Iran?

There are parallels, though not precise ones. In the 1950s, it was still possible to cut countries off from outside media and keep them isolated. The regimes of today play different kinds of games, allowing some foreign influence, or some tourists, some foreign money, some foreign media, and they try to create a balance. Some of the principles are the same: The authoritarian regimes of the present do believe, like their predecessors, in the value of controlling popular media, and civil society. That was true in the fifties, and that’s true now, really.

How are Russia’s government and society still affected by the censorship and repression of the period you describe in your book?

In Russia, television is very closely controlled by the state, newspapers a little bit less so. You can have an opposition newspaper in Russia as long as not too many people read it. But the mass media, or what the state considers to be the mass media, which is mainly commercial television, is controlled either directly or indirectly by the Kremlin.

Let’s talk about freedom of speech these days. What does the concept mean to you?

“Free speech” as an idea is meaningless by itself. It can only be exercised in a context. Free speech belongs to a culture of responsibility and rule of law. Just saying “anything you want” isn’t freedom, it’s anarchy.

Mo Yan, the 2012 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, told Granta magazine that censorship can be beneficial to creativity because it causes writers to “ inject their own imagination.” Do you think censorship had this effect on writing in Soviet-controlled countries?

There’s a very narrow species of literary writers and poets, who might imagine it’s useful or interesting to work inside a cage, but I don’t think that’s a universal sentiment. Censorship is certainly incredibly detrimental to politics, economics, and almost everything else.

What are some central/eastern European news publications or blogs that you would recommend to our readers?

Alas, the best ones are in the local languages: The best Polish newspaper is Gazeta Wyborcza, and the most famous Russian opposition newspaper is called Novaya Gazeta, which has an English website. If you want English sites, try New Eastern Europe, it covers the entire region. And Index on Censorship still runs a lot of material about Eastern Europe, Russia, and the media, too.

One Comment on "Censorship Behind the Iron Curtain and Its Parallels Today"

barism