On Filmmaker Thaelman Urgelles: The Long Road From Politics to Mentorship

by Kriti Sanghi / February 18, 2021 / Comments Off on On Filmmaker Thaelman Urgelles: The Long Road From Politics to Mentorship

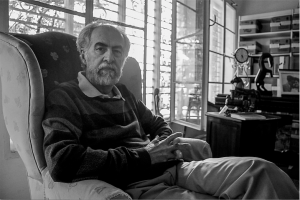

Thaelman Urgelles is a celebrated Venezuelan filmmaker, perhaps most well known for his 1982 film La Boda (The Wedding), which some consider to be one of the most influential Venezuelan films of all time. In La Boda, as in many of his other films, Urgelles probes into the undercurrents of politics and society in Venezuela.

Thaelman Urgelles is a celebrated Venezuelan filmmaker, perhaps most well known for his 1982 film La Boda (The Wedding), which some consider to be one of the most influential Venezuelan films of all time. In La Boda, as in many of his other films, Urgelles probes into the undercurrents of politics and society in Venezuela.

On a balmy day this last February not long before the world shut down for the Covid-19 pandemic, Urgelles shared the peaks and valleys of his prestigious film career with Sampsonia Way while spending an afternoon visiting the City of Asylum in Pittsburgh. His friend and former student, the prestigious Venezuelan writer Israel Centeno, translated from Spanish to English as Urgelles reflected not only upon the political maelstrom he’s tried to explore in his work — but also shared the arc of his career as he’d grown from filmmaker to activist and teacher.

For Urgelles, the political turbulence that undergirds his work is borne from the fabric of his life. His first memory, in fact, is of the national police coming towards his home. It was nighttime in Barquisimeto, Venezuela, and Urgelles was playing indoors when he looked through the window and saw policemen approaching the front of his house. He opened the front door to find that they were officers of the Seguridad Nacional (National Security). The officers asked Urgelles to get his mother, who was a prominent advocate for democracy and women’s suffrage. The young Urgelles went to retrieve his mother, unaware that the Seguridad Nacional was notorious for its ruthless cruelty towards critics of Marcos Pérez Jiménez’s regime. The agents of the Seguridad Nacional searched their house for propaganda against the regime, asked for Urgelles’s father, and then left, leaving a summons for Urgelles’s mother.

Urgelles was only four years old at the time of the incident, but 68 years later he remembers it vividly — how it influenced his efforts to use storytelling to advance the cause of democracy and truth in Venezuela throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

In 1958, six years after the police left Urgelles with his mother’s summons, a coup d’etat against Pérez Jiménez led to the advent of democracy in Venezuela, prompting a shift in the political culture of the country. Most Venezuelans were more than happy to move on and leave the past behind, but many others were left to deal with their wounds. Urgelles recalls his experience of navigating the disparate realities of this era. “I would go to school and be repeatedly told by my teachers that the police were friends of the community, that the police would protect us,” Urgelles says. “And I would then come home to my father reminding me of the past, warning me once again to stay away from the police.”

Urgelles went on to study psychology, literature, and journalism in college. After graduating, he began his career as a sports journalist, reporting from boxing rings around the city.

It wasn’t until years later when he became more active in community theater that Urgelles decided it was time for a change. After his experience operating the moviola in journalism school, Urgelles made a career shift towards screenwriting and filmmaking. It was the 1970s, and the Venezuelan film industry was in its golden age. Urgelles began working on small-scale productions: educational shorts, political documentaries, and narrative short films. Within a few years, he began directing feature-length films. He started out co-directing (Alias) El Rey del Joropo (Alias The King of Joropo) (1978) with Carlos Rebolledo. (Alias) El Rey del Joropo, which was based on Edward Aray’s novel Los Cuentos de Alfredo Alvarado, El Rey del Joropo (The Tales of Alfredo Alvarado, The King of Joropo), examined the life of the famous Venezuelan dancer-turned-criminal Alfredo Alvarado and denounced his manipulation by the media. The film became a hit and established Urgelles within the industry.

Later, Urgelles went on to direct and produce films about a topic that was close to his heart: politics. La venganza o que bellas son las flores (The Revenge, or How Beautiful The Flowers Are) (1978) was a satire about the various inequalities within Venezuelan society. The positive response it received encouraged him to dig deeper into his childhood memories for his next work. Urgelles’s next film in 1982, the widely acclaimed La Boda (The Wedding), was a snapshot of the country across three generations, various social strata, and myriad of political and cultural ideologies, all set against the backdrop of the country’s transition from dictatorship to democracy in the 1950s. Urgelles then moved on to making commercial films, including El atentado (The Attempt) (1984), La generación Halley (The Halley Generation) (1986), and various documentaries and mini-series for television.

In 1983, Urgelles co-founded the School of Cinema and TV, the first professional film school in Caracas, where he met a student named Malena Roncayolo. Soon they fell in love, married, and joined their careers. Urgelles produced the first films that Roncayolo directed: Casa Tomada (House Taken) (1985) and Pacto de Sangre (Blood Pact) (1988).

Urgelles taught the screenwriting course at the School of Cinema and TV. His favorite part was analyzing screenplays like Chinatown (1974) and Casablanca (1942), among others, with his students. It was in one such class where he met and became good friends with Israel Centeno, a writer researching story structures for the novel he was writing.

In the late 1990s, Urgelles, along with his cast and crew, wrapped up shooting for his “mystical tragedy” film Los pájaros se va con la muerte (The Birds Fly Away with Death). But instead of continuing with the post-production process, Urgelles decided to leave the film in archival film cans. He was disturbed by the undemocratic manner in which Hugo Chávez had come to power: abolishing checks and balances in the government and replacing them with his own military. Urgelles turned to community service and community organization against Chávez’s increasingly authoritarian rule. Los pajaros se va con la muerte was ultimately released in 2011.

In 2003, a documentary titled The Revolution Will Not Be Televised began making waves in the media. It explored Chávez’s rule and the 2002 coup d’état attempt, but its accuracy was disputed. In response, Urgelles partnered up with Wolfgang Schalk to release X-Ray of a Lie (2004), which thoroughly examines how The Revolution Will Not Be Televised omits key events and re-appropriates media footage out of order to show Chavez in a positive light.

In recent years, he’s remained involved in cinema, continuing to use the power of film to help democratize Venezuela — but now more so as a writer and mentor. Urgelles advised Carlos Mesber on the award-winning script for his film Malika. Urgelles has also completed a script for his newest project, which is currently undergoing development. It’s a film about Judge María Afiuni, who was arrested, tortured, and sentenced without evidence on the orders of Hugo Chávez. The project is titled “La presa del Comandante” (The Commander’s Dam), like Journalist Francisco Olivares’s book, upon which the script is based.

Urgelles’s advice to future generations of artists is to constantly move forward and while remaining ready to improve at every turn. In one story he shares with his students, he recalls the day La Boda was released: he had woken up realizing that he wanted to remove a segment of the movie. But the film had already been distributed to theaters around the city. Urgelles drove to the nearest theater and went straight to the projection room, where he cut out two minutes worth of film and pasted the remaining strips back together. He rushed, driving from movie theater to movie theater around the city and trying to cut and paste the film in time.

It’s a lesson in perseverance and faith in one’s vision, something that, today, he hopes to see future generations of storytellers carry forward.