Hind Shoufani: Unsanctioned Writing from the Middle East

by Joshua Barnes / February 11, 2013 / No comments

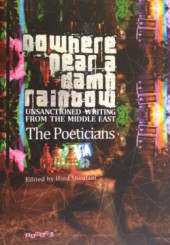

The story behind Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow.

Hind Shoufani is a poet and filmmaker, who created an anthology of Middle Eastern poetry. Photo: Greg Bal.

The poet and filmmaker Hind Shoufani remembers how the Poeticians, the collective she founded in 2007, started: Fourteen people were drinking, smoking, and sharing their poetry in her purple living room in Beirut. Someone was playing the guitar and someone else suggested that they go perform in public; all of them thought it would be a one-time thing, but now the collective has performed in Amman, Dubai, and Beirut over 50 times, and provided a forum to at least the same amount of poets.

Shoufani also remembers the informal conversations in which they considered publishing a Poeticians anthology, and how—just like what happened with the collective—the idea came to fruition with surprising speed.

In 2012 Zena el Khalil, a member of the Poeticians and co-founder of xanadu* art collective/press, suggested publishing the first Poeticians anthology to coincide with the upcoming Hay festival in Lebanon. But to do that El Khalil and Shoufani barely had a month to gather the material, edit it, create a cover, and send it to be printed. As if the situation was not difficult enough, El Khalil was living in Beirut and Shoufani in Dubai.

Many 6-hour skype calls shrunk the distance, but not the difficulty of finding a title; the results of their brainstorming sessions didn’t please them at all. That’s why, the day that El Khalil was sick and blurted out, “We should just bloody call it Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow,” they laughed and moved on. But after tens of back-and-forth emails with some of the 31 writers selected for the book, the pair decided to go with the fever-induced title. Later they added the subtitle “Unsanctioned Writing from the Middle East.”

The 350-page Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow is a pioneer of its kind. It compiles 111 poems in English and Arabic, and opens a window for writers from many nationalities who have resided in one of the three cities where the Poeticians perform. It would be difficult to find another anthology from the Middle East that includes such a diversity of writers, nationalities, styles of writing, languages, ages, and gender.

In this interview, conducted via email, Shoufani talks about the selection process for the book, the importance of uncensored writing, and the path of the Poeticians. In the eight following installments of this series, Sampsonia Way will present some poems from the collection and interviews with their authors.

Why do you think that the writers agreed with Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow as a title?

The conversation that led to this title was about the notion of the Arab spring: The fact that we are nowhere near a proper political upheaval in the Arab world, and that, despite the incredibly inspiring revolutions that have happened recently, we are still nowhere near where we need to be as a region.

It’s a title that’s slightly filled with anger and wants to be truthful and not nostalgic or naïve about the price people have been paying for change to come. Since the term “spring” has been bandied about, we thought, rain, flowers, rainbows, calm after the storm, etc. We cannot see a rainbow yet, and we like rainbows.

In the end though, does the title of a poetry book really have to properly mean anything? We don’t believe so.

As curator of the book, can you talk about the selection process?

We asked over 50 people who have read with the Poeticians for several poems. Some didn’t respond, having moved to far away locations and different lives. Some responded too late. We went with the largest number of poets and poems possible in the time we had. I picked the poems I thought were the best. I hope to include more people in the second anthology, allowing for more time if they are not in the region to prepare the work.

What did you want to show in this selection?

The diverse range and voices of people performing in the Middle East. How brave some people are in their opinions, their love stories, their experiences with war and loss, and their identity and faith.

Mostly, I wanted the poets to be happy with the book: xanadu* publishes poetry for social change; it’s a project that aims to change the lives of young artists by giving them a chance to be seen and be confident in their work. It also aims to offer readers here a local perspective stripped of artifice, classical bounds, and propaganda.

Personally, we also wanted to show the world what a small group of dedicated women with dynamic personalities, ambition, and loud voices can do when they work together—whether in literary disciplines, or in business ventures, or any sort of cultural community work.

The book is subtitled “Unsanctioned Writing from the Middle East” and you have described it as an “uncensored” collection. Why are you highlighting that this book is uncensored?

We publish poetry in English. The combination of this makes it difficult for the mass public in Arabia to read us. On the other hand, it also allows us a little less hassle in dealing with the censors. As far as I know, every play, film, book, etc, has to go through the censorship office before it’s allowed to be shown or sold to the public. Lebanon probably has the most lax rules on this, as it’s one of the most liberal Arab countries, but even though they let a lot slide, if we actually read their rules and regulations, we would be shocked at how backward and oppressive they are.

What topics does the book address that would be censored in the Middle East?

Most content in the Middle East is censored for sexuality, politics, and religion—topics we relish tackling, writing about, exploring, and publishing. We hope they are not offensive, but we also appreciate not having anyone remove words, lines, or entire poems.

We wanted to add that subtitle to the book to make it clear to people that we were the sole editors of this work, and that we encourage free speech.

What about self-censorship?

We are bound by some social norms. In this region it is easy to get in trouble for feisty opinions, especially on civil marriage, religious sectarianism, atheism, premarital sex, homosexuality, and other hot topics. It would be really great to pretend that each of us are past worrying about publicly speaking about these issues, but the truth is we’re not. It’s not 100% safe. Nonetheless, we tried to be as honest as possible, and as under the radar as possible.

What is this book doing that similar books in the region can’t do?

It doesn’t compile work from a particular kind of writer, or style of writing, or even nationality, language, age, or gender. It’s a very specific, small community, and we are trying to shy away from the prose, style, presentation, and sales methods of classical poetry. I personally have not seen many anthologies published in the region that include work by writers based here, in English, with the sort of diversity we have embraced.

- Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow Writers Profiled in SW

- • Zeina Hashem Beck, Lebanon

- • Jehan Bseiso, America/Jordan

- • Frank Dullaghan, Ireland

- • Nigel Holt, United Kingdom

- • Justyna Janik, Poland/Canada

- • Zena el Khalil, Beirut

- • Mazen Zahreddine, Beirut

- • Rewa Zeinati, Saudi Arabia

The 31 writers included in the collection come from many places and seem to have spent time all over the globe—much like yourself. Can we talk about exile as a pattern among these writers? How is the concept of exile reflected in the book?

I wouldn’t go so far as to speak of exile in the book in general, even though that’s a sexy concept. It certainly applies to the Palestinians in the book, and there are several of them. Palestinians are scattered all over the world, and I would dare say that they are instinctively drawn to storytelling because their personal stories are so political, and their family heritage is usually rife with separation, anxiety, pain, and alienation. However, the poets in the book have lived in either Beirut or Dubai. Those are two different scenarios.

Can you describe those scenarios?

Beirut is a place where many local writers and artists use English to produce their work. It’s also a city that attracts short-term residents via various NGOs, universities, cultural residencies, and journalistic assignments. We met several of the non-Lebanese poets in the book during the few months they lived in Beirut, and they contributed to our Poetician events. For them, it was a chance to interact with funky crowds and good artists in a space where they can relax and the language works in their favor.

In Dubai the population is a mix of dozens of nationalities. The expats comprise most of the labour force in Dubai, and therefore, any collection of poets meeting monthly, writing and workshopping together, are bound to be of very diverse backgrounds. They are not in exile, and have chosen to come work in Dubai. The Poeticians provides them with an extra-curricular experience unlike any other in Dubai, which is a stiff and boring city compared to the mania and delirium of Beirut—at least, for poets.

What does the name Poetician mean?

I take it to mean a poet who cares about society—values, ethics, politics, sociology, love, loss, land, and war. I am sure the meaning exists somewhere online, but I’m not sure you would find the word in a classical dictionary. It was penned by one of our first poets, a dear friend of mine, named Maral.

Why did you start the Poeticians adventure?

I wanted to hear other people perform their poetry and spoken word and I wanted to perform my own poetry. I didn’t find a local group who did that in a way that I liked, so I started one.

Shoufani wanted to show the range of voices performing in the Middle East in Nowhere Near a Damn Rainbow. Photo: Greg Bal.

Can you summarize the success of the group?

I cannot summarize the successes in any way that could possibly explain the group’s impact on individuals and audiences; words wouldn’t do it justice.

But recently, having seen so many charged, powerful, and mature performances from many of our long-time poets, I feel that the successes far outweigh whatever shortcomings I believe I have, and I am deeply pleased, honored, and slightly surprised by how appreciated we seem to be in the cities we perform in.

What about the failures?

The failures are many and easy to talk about. I would like us to be a legal entity of sorts, to be able to launch a full yearly festival of poetry and spoken word sometime in the future. I would like to have the time and resources to put all of our videos up on our vimeo page. I would like to be able to not turn down so many writers who don’t blend in with our concept, content, and style. It pains me to tell people their work doesn’t quite make the Poetician stage yet. I would also like to be able to publish people’s work a lot more on our blog, create more events, and follow up with more writers individually, including hosting private sessions for them to give each other feedback. The list goes on.

This is a totally non-profit project for me, and we have turned down any corporate sponsors or partners for events in Dubai, so our time is not compensated in any currency aside from love and gratification. I made this choice and I stick to it. No sponsors or interference from anyone for the poets.

What is next for you?

A third book of my own poetry. Also, my first feature-length documentary film will be released this year. Then there’s the second Poeticians anthology, soon if possible, and a experimental poetic novel I have wanted to write forever, hopefully to be completed in 2014. I will visit Palestine as soon as I am allowed, and spend some time in Berlin. Of course there’re film festivals, more poems, long walks in Brooklyn, performances in Dubai, and workshops of all sorts. In between all of this I want to learn about Haiku.

On a larger level, more love, more inner peace, more glitter, a better commitment to belly dance classes, avocados with cumin cheese, mourning and grieving for my father, honoring my mother’s maternal spirits, and the hope that I continue to be able to write freely, no matter where the wanderlust takes me.