One Loses the People, Because He Loses Their Hearts

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / March 12, 2014 / No comments

In which a Uyghur academic predicts his own disappearance.

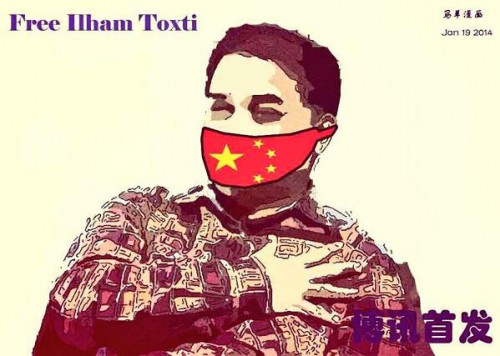

Image by Twitter user @HisOvalness.

He foresaw the outcome almost a year ago. In July of 2013, Ilham Tohti, a 44 year-old Uyghur scholar and lecturer at the Central University for Nationalities in Beijing, told Radio Free Asia (RFA) that he had the feeling that his “peaceful days are numbered.” Following this, he left a statement to be published in the event of his disappearance. There are four points in the statement:

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

1.If Tohti dies in the near future, it is not a natural death, and he would never commit suicide.

2.He does not want to have an appointed lawyer.

3.He will never say things against his morals and principles, nor harm his Uyghur compatriots.

4.He has never associated with terrorist organizations or foreign-based groups.

Tohti emphasized that he has “relied only on pen and paper to diplomatically request human rights, legal rights, and autonomous regional rights for the Uyghurs.”

On January 15, Tohti disappeared. Now he is behind bars, far from his home and family. On the day of his disappearance, three dozen local and Xinjian security police raided his home in Beijing. They confiscated all of his electronic equipment, including four computers and three cell phones. They also took his CDs and DVDs, other research materials, and even his students’ homework and exams. The safe containing his ID and bankbooks was also confiscated. On the same day, seven of his Uyghur students, along with their laptops, iPhones, and bankbooks, were taken away by the police. Two of the female students were released in the evening, but the whereabouts of the others are still unknown.

A month later, on February 20, Tohti’s formal arrest was announced. An unusual thing that worries both his wife and assigned lawyer, Li Fangping, is that the authorities moved him to the Urumqi detention center in Xinjiang province. Located in the middle of the Gobi desert, it is over 2000 km away from Beijing. Tohti has studied and worked in Beijing for decades and is a resident of the city. According to the law, Tohti should be tried by the Beijing local court; there is no legal basis to send him back to his hometown. He is also accused of “separatism,” a charge that could come with a heavy sentence—possibly even the death penalty. While these days political prisoners in normal cases aren’t sentenced to death in China, Xinjiang province is the exception. Can this mean that Tohti is in more danger?

Tohti is courageous, but not blindly impulsive. He runs the website Uyghur Online to promote his mild and reasonable political thoughts. He does not appeal for independence, but true autonomy, peace, and rule of law in the Xinjiang-Uyghur region. His good friend, the Tibetan poet and blogger, Tsering Woeser has collected some of his words to illustrate his thoughts:

“There is a tendency in Xijiang to ‘magnify the terrorism.’ Under the name of anti-terrorism, other problems are covered up—e.g. the inability of the local government as well as the Stability Maintenance Office. The main problem in Xijiang is neither terrorism, nor anti-terrorism; it is the problem of (uncontrolled) power, the inequality of power and the monopoly of power through vested interest groups.”

“I see in Xijiang that the more they suppress religion, the more that Uyghurs protect their religion…What should the government do? Not using pressure, it needs to work on itself. If it can’t manage its own business, it can’t rule the country. If they don’t change their thoughts and manner towards the Uyghurs, if they don’t respect people’s right of expression, including self-determination, then the conflict between the Uyghurs and the government will grow stronger and stronger.”

Tohti’s criticism is not inciting in nature, but it tells the truth and exposes the reality of the situation. Of course, this means it also scratches some of the authority’s exposed nerves. Tohti intuitively knew the dangers of his role as a critical Uyghur writer and could almost predict his imminent fate: Arrest, detention, physical and mental torture, and murder. So he prepared the written statement above and consigned it to RFA.

The US government and the EU have condemned Beijing for Tohti’s arrest. Protests come not only from the Uyghur overseas group, but also from Chinese intellectuals. Beijing’s nationality policy—migration of Han Chinese to minority regions, combined with political suppression, and economic deprivation—has ignited sound and fury and seeded frustration and hatred in Tibet, Mongolia, and Xinjiang. Even though Tibetans can draw spiritual sustenance from Buddhism and receive consolation through the Dalai Lama, whose merciful wisdom prevents the breeding of radicalism, many Tibetans still self-immolate to show their desperation and strong protestation. With their Muslim culture, the Uyghurs do not have a spiritual release valve for their depressed feelings. So they apply the usual means of fighting against the new form of Chinese colonialism. Bloody confrontation is unavoidable. Violence between Uyghurs and the police occurs frequently, and even in the most recent terrorist act in Kunming on March 1, the Uyghur people have been blamed as perpetrators.

Mr. Wang Qishan, a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, is the adviser to party chairman Xi Jinping. Wang introduced French historian Alexis de Tocqueville’s (1805-1859) book, The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856) to Xi and the whole ruling apparatus. The book presents this message: “The outbreak of the French Revolution was not during the most brutal era of oppression, but in an era of relatively light oppression, during the reform era of feudal dynasty.” Well, a dictator can never act alone; he needs his lackeys. We may remind lackey number one, Mr. Wang, that there is no need to re-appropriate European intellectual property; he should read our ancestor Mencius’ (372-289 BC) book, in which he will find this sentence: “The one who loses his people, loses the world; one loses the people because he loses their hearts.” And, as far as quotes go, Mr. Wang, this one is more useful and enlightening.