Two Forgotten Spies: Bianca Tam and Antonio Riva

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / February 17, 2017 / No comments

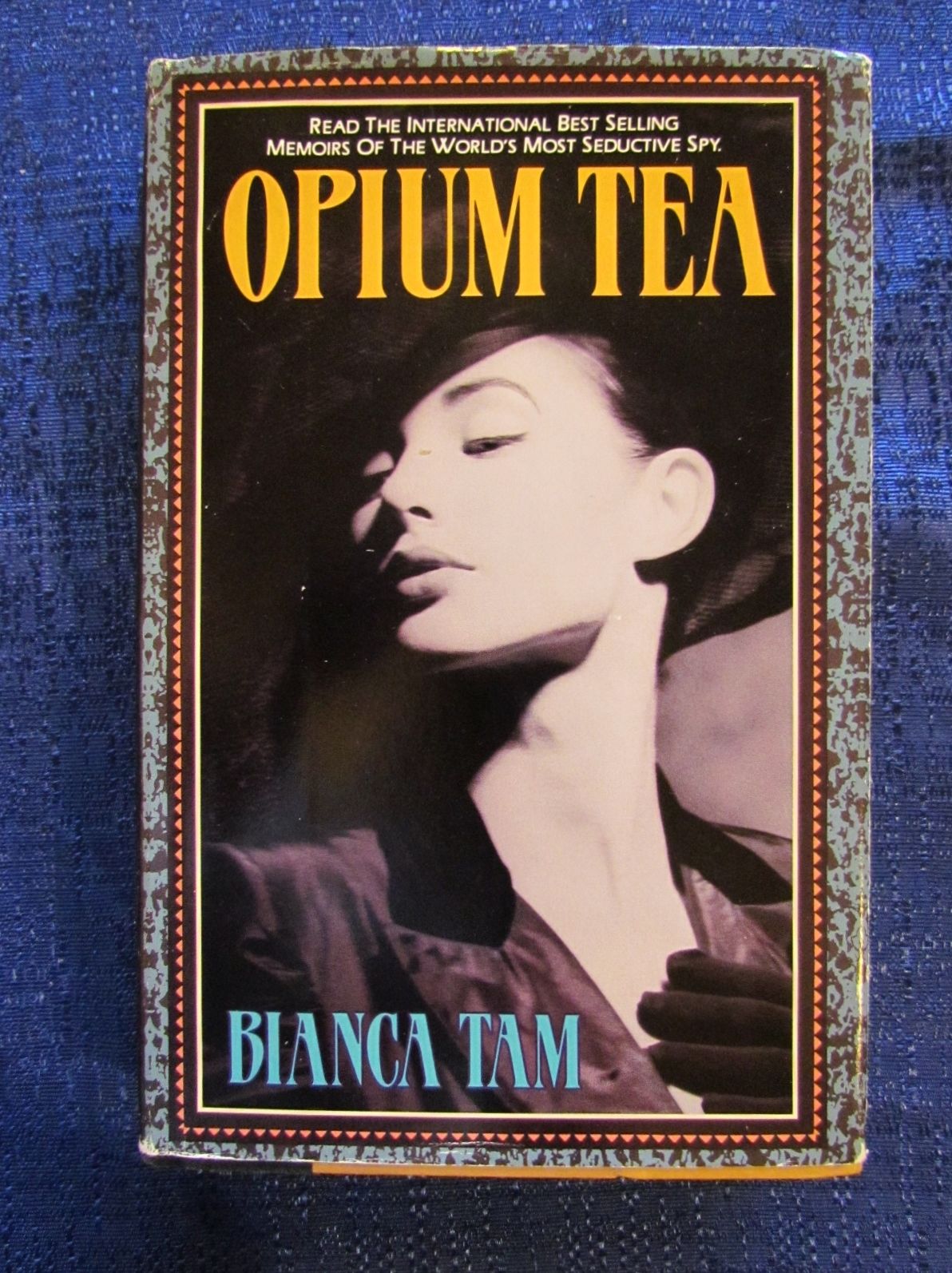

Opium Tea, the memoir of Italian spy Bianca Tam.

Foreigners in China, in the mid-twentieth century, were active in the resistance against the burgeoning Communist regime. The stories of two Italian spies have been largely lost in history. Tienchi Martin-Liao seeks to shine light on the pair’s forgotten histories by retelling the story their opposite fates.

Recently I came across to two books, Opium Tea and L’uomo che doveva uccidere Mao (The Man Who Should Kill Mao). Both volumes are about two Europeans who acted as spies in China in the forties during the Sino-Japanese War and the civil war between the Kuomintang and the Communists.

The real spy, Bianca Tam, received amnesty and could go back to her home country of Italy and enjoy the fulfilling second part of her life. Meanwhile, the falsely accused spy, Antonio Riva, was sentenced to death and executed right after the trial. Justice or injustice, fortune or misfortune—all are gone with the wind.

Bianca Tam (1918-1994)—the author of the autobiography Opium Tea (first published in Italy in 1985, later translated into English, French and Japanese)—was a daughter of the noble Medici family. She was eighteen when she fell in love with a Chinese foreign exchange student at the local military academy, Tam Zhanchao. They married, and Bianca followed her husband to China. While her husband was fighting at the front, she gave birth to four children.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison til 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners, and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

In the middle of the war, Tam Zhanchao was wounded and fell in love with a nurse. He left Bianca and the kids to build a new family. In order to support her four little children, the beautiful Bianca Tam worked all kinds of jobs, including modeling for Christian Dior. She became a social butterfly in Shanghai, moving around an international circle of rich, influential business men, diplomats, politicians, etc. Bianca used her expansive social network to collect information for the Japanese and was handsomely paid.

When the war ended with Japan’s defeat, Chiang Kai-shek’s government arrested the attractive spy and sentenced her to death.

At this moment, her estranged husband Tam reappeared to rescue her. He visited her in jail frequently and Bianca became pregnant once again. Finally Generalissimo Chiang granted amnesty to the woman and she was allowed to return to Italy with her the children, while Tam moved to Taiwan with his family where he died of cancer in 1960.

In 1947, at the age of 29, Tam returned to Italy with her children for the second part of her legendary life. Thanks to her modeling career in Shanghai with the French designer Christian Dior, she became a famous model and public darling of Paris.

In 1993, during the Gulf War, an Italian magazine hired Tam as a reporter. She traveled to Kuwait and filed stories from the warfront.

In 1991, three years before her death, a stranger visited her from the United States. It was the daughter of her deceased ex-husband and the nurse. She had discovered Bianca through the publication of Opium Tea. It was an exciting affair: The next generation of the Tam family—four children on Tam’s side and five on Bianca’s—finally reunited and reconciled. This happy event marked the end of the disastrous 20th century—a century full of pain, divisiveness, sorrow and agony born from war. Demonstrating love and human bonds always survive.

Yet, Bianca’s countryman, Antonio Riva (1896-1951), was not so lucky.

Riva was in the wrong place at the wrong time and paid for this with his life. He was picked out as a sacrificial offering to the newly founded People’s Republic of China. During World War I, Riva served bravely as a pilot in the Italian Air Force. For his seven aerial victories, he was awarded the Silver Medal for Military Valor and the Knight’s Cross of the Military Order of Savoy—high honors in the Italian Air Force.

Many details about Riva’s life and death remain a mystery. We do not know how he became a spy or why the Communist regime decided to accuse him—along with five other foreigners—of conspiring to assassinate Mao Zedong and the other founding fathers of the People’s Republic at the celebration festival at Tiananmen Gate on October 1, 1950. Official records of the event have not yet been released to the public—and may never be.

The Italian journalist and sinologist Barbara Alighiero spent many years in China collecting valuable materials and analyzing this case of injustice. After years of research and interviews Alighiero published the book, L’uomo che doveva uccidere Mao (The Man Who Should Kill Mao), in 2010. The book provides the reader with a more reliable version of the story so that we can understand the background of all seven victims as well as the political circumstances during those post-war years:

After he left the Italian Air Force, Riva established “The Asiatic Import and Export Co.” in Tianjin. He leveraged his company to trade weapons. In the thirties and forties, He assisted the Kuomintang Party (KMT) by training pilots, building airports and buying airplanes from Italy, not only to fight against the Japanese but also to suppress the “Communists.”

The young Communist Party was founded a decade ago in 1921 and was so small and weak, Chiang Kai-shek wanted to eliminate it before it became a real threat. Riva as a pilot and business man understood how to satisfy Chiang’s need, after all, he did not like the communists either. Riva married an American woman and they had four children. He loved books and arts and collected antiques and calligraphy. Many foreigners and other Europeans around him did not want to leave China after the war was over. They wanted to stay in the country and enjoy life as privileged foreigners.

Ruichi Yamaguchi, a Japanese intellectual, loved Chinese culture, and as a bookworm he worked happily at the bookstore of the Frenchman Vetch. Both Yamaguchi and Vetch were friends and neighbors of Riva, as well as the Italian priest Tarcisio Martina, Quirino Victor Lucy Gerli, and the German engineer Walter Genthner. The American diplomat and military attaché at the American embassy, Colonel David Dean Barrett, was also their mutual friend. Barret was an old hand in China who was the assistant of general Joseph Stilwell during his mission in the Chinese, Burmese, and Indian Theaters of World War II. When the civil war broke out and the communists came to power, Barrett chose to leave for Hong Kong. This decision saved his life, or at the very least, saved him from imprisonment.

In September 1950, Antonio Riva, Yamaguchi and the other four foreigners plus Ma Xinqing, a Chinese native , were arrested. When they found an old mortar in a house raid, the authorities alleged that the group conspired to plant a cannon at Tiananmen gate to kill Mao Zedong and others. This antique mortar was nonfunctional– Riva had collected it from a junk pile at the outskirts of Beijing.

Of the seven defendants, only Riva and Yamaguchi received death penalty. The others received life sentences or lengthy prison sentences.

It was the first time that the Chinese government had executed foreign citizens in China. And while the news shocked the international community, most other countries were struggling with their own postwar problems and lacked the strength advocate for a handful of innocent people.

As the French sinologist Jean Luc Domenach wrote in preface of Alighiero’s book:

“The beginning time of the Red regime was extremely horrible. It closed the door and beat the dogs, purges and killings went on without leaving any trace…She [Alighiero] has told a true story, with false fabricated facts to accuse several foreigners, it was an imaginary plot.”

The Chinese Communist Party had taken power through war and violence. They believed blindly in terror and blood. As the Chinese proverb goes, “Kill the chicken to scare the monkeys.” The Party wanted to warn its subjects and the outside world through these unjust trials: We are the masters, we are the rulers, we can do whatever we want, no one shall intervene.

Yet, there was an obstacle in this absurd and ferocious trial: Mao’s regime did not dare test America. The American David Barrett, was deeply involved with the “conspiracy.” Yet he alone remained free and untouched. Twenty years later, Premier Minister Chou En-lai invited Barrett to visit China and apologized vaguely for the case. These apologies can be understood as a confession to what was nothing but a fabricated political plot.