Bewketu Seyoum: Using Literature as a Counter-Narrative Weapon

by Chalachew Tadesse / March 25, 2016 / No comments

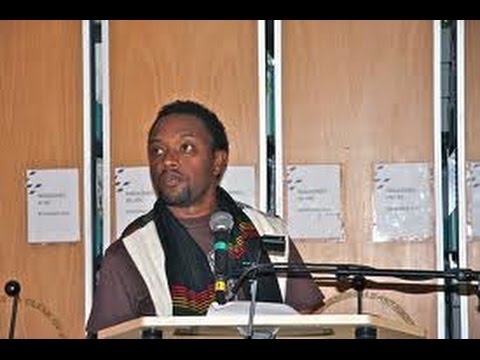

Ethiopian poet and essayist Bewketu Seyoum reciting his work. Image via Youtube user:

Yehabesha.com

Despite political turbulence and aggressive censorship amid the Ethiopian government, poet Bewketu Seyoum continues to critique the ruling party.

Due to the overbearing nature of Ethiopia’s ruling Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), informal and self-imposed censorship are commonplace. It is no secret that the publishing and distribution of books is largely under the government’s direct and indirect control. Nevertheless, censorship or not, it is indisputable that literary works are not entirely influential in exposing the regime’s serious follies to the extent that books could shake the EPRDF to its core.

- This column’s topics will include literature, art, education, history, and political culture in Ethiopia, as well as society and politics in the Horn of Africa. Moreover, I will address the tribulations of journalists and the ill-fated constitutional right of freedom of expression under Ethiopia’s deceptive authoritarian regime. I will try to be the voice of the voiceless, be it persecuted journalists at home or exiled journalists abroad. These themes will make Ethiopia’s uniqueness and absurdities evident.

- Chalachew Tadesse is an Ethiopian journalist and columnist. He has previously worked as a full time journalist for The Reporter and The Sub-Saharan Informer English newspapers. He was also a columnist for the much-acclaimed Fact magazine, before the Ethiopian regime closed it in October 2014. A political science student by training, he works as a university lecturer and is known for his sociopolitical commentaries on the Ethiopian private press.

Without a doubt, satire and poetry form part of the normal Ethiopian way of life. Due to the long tradition of oppression, Ethiopian poets and writers, in sharp contrast to the western rational mode of communication, have long been using q’ene (otherwise known as “Wax and Gold”) where they use a verse or a word with both disguised and explicit meanings at the same time. Mind you, not all poets have the craft to compose and recite q’ene though, but only those with in-depth knowledge of the Orthodox Church’s teachings.

Political satire and poetry obviously play pivotal roles to express dissent in excessively oppressive regimes like Ethiopia’s. However, expression of dissent have been a rarity in Ethiopia. Partly out of fear of reprisal and partly due to lack of tradition, even the independent media rarely uses satirical political cartoons to mock power holders. In Ethiopia, many things about power holders are considered de facto unsayable.

Even in the ongoing violent popular protests against the government–which have been underway in Ethiopia’s largest region of Oromia for four consecutive months—political, satirical, or graffiti art is hardly noticeable. If repression had not hardened the society’s emotions, they would serve as safety valves or, I would say, lubricants for popular dissent. Meanwhile, I must note that the authorities arbitrarily detained Bloomberg correspondent William Davidson and freelance journalist Jacey Fortin for 24 hours in the beginning of this month while they were covering the protest which claimed more than 140 lives in less than four months due to indiscriminate use of lethal force.

Over the last few years, however, some explicit and underground political satires and poetry critiquing the lack of freedom of expression, social injustice, corruption and state repression have come out. Partly for historical reasons, Ethiopia is apparently known for its lack of literary writers in the English language. A handful of famous contemporary writers and poets abroad–namely Hama Tuma, Lemn Sissay, Nega Mezlekia, Maaza Mengistie and Dinaw Mengistu–can be mentioned though. In this article, I focus on one young contemporary and famous novelist, poet and socio-political satirist Bewketu Seyoum, who is still in his mid-30s. In 2008, he won the Ethiopian best young writer award. Apart from publishing books, he used to contribute satirical and non-satirical articles regularly to Addis Admas and Addis Neger newspapers and Fact magazine, where I was a columnist. Being a soft-spoken publication, only Addis Admas has to date survived the regime’s press crackdown.

Bewketu has won the hearts and minds of not only Ethiopians, but the foreign literary community as well. Four years ago he was invited to present his poems at the 2012 London Olympics. During that occasion, he had the privilege of reciting five poems, with a stage performance, to a large British literary audience in Manchester City. Interestingly, the world-famous Ethiopian-born poet Lemn Sissay–a foster child of the British government as he often describes himself–is already a shining poet in the whole of United Kingdom, including Manchester. Mind you, Lemn Sissay was elected Honorary Chancellor of the great Manchester University last year. I quote verses from one of Bewketu’s poem recited at Manchester Hall:

I want to be a river

I want to be a river

So that I can emigrate to foreign lands

Without ever having to leave my own country

No matter the regime’s behavior, Bewketu has had the courage to use political satires, melancholic humor and poetry–mildly or explicitly–to critique the prevalent repression, corruption and social injustice in Ethiopia. He has become especially more outspoken and unequivocal after setting foot in the United States for a literature fellowship at Brown University last year.

By distributing stories and political satires on CD, Bewketu, a talented and much acclaimed storyteller, has successfully used the new media to reach a large audience. His works are peculiar in that they indisputably appeal both to the younger and older generations alike. The young writer published three much-acclaimed collections of poetry, namely Nwari Alba Gojowoch (Unmanned Huts) in 2002, Barari Qeṭaloch (Flying Leaves) in 2004, Yesat Dar Hasaboch (Fireside Meditations) in 2009, and two best-selling short novels, Mewtat Ena Megbat (Getting Out and Getting In) and Enqilf Ena Edme (Sleep and Age).

A month before publishing his poetry collections, Bewektu published KeAmen Bashager (Beyond Amen), a collection of imaginative, humorous, satirical and historical essays. The work constitutes avenues of resistance, contest, rewriting and alternative narratives about the present Ethiopia and its overly politicized past. Essentially, Bewketu’s work is as a counternarrative of dystopian Ethiopia, defying the incumbent government’s Utopian narrative that paints the country a rosy picture and romanticizes the ruling EPRDF. In fact, had it not been the weakness of our literature, the state media is hardly capable of constructing a strong and coherent narrative about the ruling regime and persona of the top men in power. The fictitious and superficial state narrative, which unfortunately seems to have been swallowed by the West, portrays Ethiopia as the fastest growing country in Africa. Paradoxically, in the famine-stricken country more than 15 million people currently need emergency foreign food aid.

In KeAmen Bashager, Bewektu scorned the regime for using Chinese-made surveillance technologies to spy on its potential or bona fide critics. Knowing that it is a narrow ethno-centric minority regime, the government always has nightmarish fears of being surrounded by vicious enemies, real or imagined.

As he is a versatile towering literary writer and poet, Bewketu’s works span from politics, religion, culture, morality, sexuality, social justice to history. Since Orthodox Christian religion defines the daily lives the majority of Ethiopians, he has however earned verbal and physical attacks by religious fanatics in retaliation for his pieces that were thought to be “blasphemous.” In fact, Bewketu is a Christian-turned-atheist by his own admission. Leaving the “blasphemy” claim aside, many see him as a rebellious writer who has defied the conventional way of thinking and style of writing. Yes, most of his literary works defy what he calls “old-fashioned socio-cultural, religious and political taboos” which without doubt are impediments to social change. Seen from this perspective, Bewketu can be considered as, I would say, a midwife helping the birth of a new era in Ethiopian literature. Or he can be considered as a “gadfly” stinging the regime in power as well as society in general to cure its own illnesses and transform for the better.

Were he a criminal offender

terrorizing the world

abattoir or burglar

We would not have called Pushkin Alexander

Habesha by his grandfather

(The Russian poet and playwright Alexander Pushkin is historically believed to have an Ethiopian descent by his grandfather so much so that a public square in Addis Ababa is named after him. The word habesha is synonymous with the word “Ethiopians.”)

Mixing and blending

Humor with smile

Laughter with mockery

And even if we spill it into the sea of sorrow

So vast is the sea

Never changes its color

So does the above poem, expressing his dream that the Ethiopian sea of sorrow is too vast to easily give in to satire and humor, thereby reflecting the challenges of satirists to frame strong messages.

In yet another poem, Bewketu composes:

Melted was a gun

To make a sickle out of it

For not the heart, but

only the metal’s form changed

the blade meant to cut grasses

chopped several men’s neck instead

By these verses, he preaches about soul-searching for real positive virtues by being liberated from uncivilized and dangerous socio-political vices.

Lastly, in a poem titled “In Search of Fat” (also the title of a poetry collection book translated to English), he composed as follows about the brunt of corruption and social injustice on ordinary people:

Thousands of thin people, all skin and bone

“Where is our fat?” they shout,

rummaging through valleys and trenches,

searching and searching, over hills, in the sky

At last they find it, piled up on one man’s belly!

(translated by Chris Beckett)

Bewketu even blames the morally bankrupt and politically corrupt political system for the wide spread moral decadence, prostitution and youth delinquency in the country. Among Ethiopian literary writers at home, Bewketu is the only towering figure so long as speaking truth to power through humor and craft is concerned. Most are victims of the dark clouds of fear hovering over them for 25 years. Now, Ethiopians ask one question: Will Bewketu return home upon completing his fellowship in the US? Given his increasingly outspoken critique against the regime, many have serious doubts.