“You have to pay a five cent bullet fee.”

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / May 13, 2015 / No comments

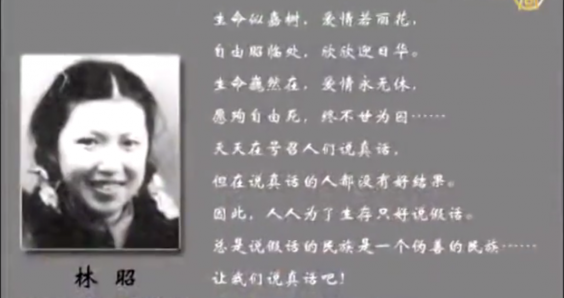

Dissident poet LIn Zhao is still idolized in China. Photo via YouTube user: ChinaForbiddenNews.

Lin Zhao’s ghost still lingers over her beloved country.

47 years ago, 36-year-old “rightist” poet Lin Zhao was executed in Shanghai. The anniversary of her death was on April 29. The Military Control Commission of the Shanghai Public Security, Procuratorial Bureau and the Court of the People’s Liberation Army made the verdict and sentencing for her crime, described as the following: “During her imprisonment, counterrevolutionary Lin Zhao stubbornly toughened her counterrevolutionary stance and continuously practiced counterrevolutionary activities. She wrote numerous counterrevolutionary diaries, poems and articles, maliciously cursed, and evilly defamed our Party and the great leader Chairman Mao, and madly attacked our proletarian dictatorship and socialism.” Two days after she was shot, security knocked on Lin Zhao’s mother’s door and told her: “Lin Zhao was executed on April 29. As her family member, you must pay a five cent bullet fee.”

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison til 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners, and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

In August of 1980, 12 years after Lin Zhao’s execution, the Shanghai People’s High Court exonerated her of her crimes, declaring that she was wrongly accused and wrongly sentenced. Liu Zhao’s name was cleared.

Another twenty years passed. In 2004, the filmmaker Hu Jie produced a documentary film: In Search of Lin Zhao’s Soul. People began paying attention to this woman’s tragic legend. A small group of human rights activists collected money and constructed a tomb for her in her hometown of Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Each year on the day of her death, people gather before her tomb to commemorate her courage.

This year, several hundred people from different provinces traveled to Suzhou, planning to hold a memorial service in the Lingyan Shan cemetery. Yet the police arrived earlier then the travelers. They controlled the train stations and told nearby hotels and guesthouses not to provide rooms to these visitors. Six guests who already checked in were thrown out of the guesthouse. The owner apologized; he could do nothing but obey the authority’s order. Police in black uniforms cordoned off the area around the cemetery to prevent the memorial service from taking place.

Who is this woman? Why is the Chinese authority still afraid of her almost half a century after her death?

Lin Zhao’s true name was Peng Lingzhao. From 1954 to 1957/1958, she was a talented student of literature and media science at Beijing University (then called Peking University). In the course of her studies, Lin joined the lyric society and became a devoted editor for the student magazine. She experienced the turbulent Anti-Rightist Movement, where her good literary and political comrades like Zhang Yuanxun and hundreds of thousands of others were falsely condemned as “rightists” just because they followed the Party’s request to “let a hundred flowers bloom, a hundred schools of thought contend” and spoke out in criticism of the communist government. What they did not know was that Mao and the Party labeled all the critical intellectuals as “snakes,” a dangerous, unstable factor for the new regime. Snakes have to be lured out of their hiding places and eliminated.

The campaign destroyed the lives of millions of people, even though the official number is only 550,000. Along with 1,500 other students and teachers from Beijing University, Zhang Yuanxun was expelled and banished to remote provinces for over two decades. Shocked by the cruel political purge, Lin Zhao attempted suicide. Fortunately, she was rescued, but was sentenced to three years of “reeducation through labor.” Ill and weak, she served out her sentence in the journalism reference library in Beijing, working under supervision of the school’s authorities.

Lin Zhao struck up friendships with other young activists. Together they founded Shooting Star, an independent literary magazine. For the first issue she wrote and dedicated a long poem, titled “A Day of Suffering for Prometheus,” to the millions of victims of famine victims who had starved to death as a result of Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958-60). Ill with tuberculosis, Lin Zhao was briefly allowed to go back to Shanghai with her mother to recuperate in 1959. She converted to Christianity. In October of 1960, Lin Zhao was arrested again. She was released once more on medical parole, but was thrown back into prison in 1962 and sentenced to 20 years. When the Cultural Revolution broke out, radicalism swept through the whole country. Her “counterrevolutionary” case was overturned to a death penalty in 1968. The execution immediately followed.

While Lin Zhao was in prison, she was severely tortured. She had to wear handcuffs and shackles, day and night for months at a time. Her struggle, the cruel atrocities she endured, was similar to the legend of Prometheus: bloody and insane. It’s possible the wardens believed that she was mad and ignored her, giving her the opportunity to write poems, diaries, and articles with available paper and ink. If those were not available she used any sharp items she could get, dipping into her own blood. She wrote on the wall, on her clothes, on the bedding. It was said that she composed 140 thousand characters of writing, miraculously left to her sister after Lin Zhao’s execution.

According to analysis of filmmaker Ai Xiaoming, Lin Zhao was out of her mind in the last few years of her life. Her final scripts (only seen by very few people, including the filmmaker Hu Jie) were more raving then rational. She wrote a fictional story about a romance and wedding between her and the dead Shanghai Mayor Ke Qingshi. The two never had any personal contact. Possibly, there was no posthumous publication of her prison scripts because her sister, who now lives in the United States, and her close friends believe that to do so might damage the pristine image of a hero.

Lin Zhao’s admirers idealize her by comparing her to Joan of Arc and calling her a “holy Virgin.” In China today, where liars, cowards, denunciators, and villains are commonplace, people long for saints and martyrs. Lin Zhao was brave and noble, but physically and mentally she was not unbreakable. We do not know when she lost her mind in prison, but maybe it was the “madness” that heaved her from a mundane existence. All of her suffering and desire, all of her fear and conscience were sublimated. Perhaps losing her mind led Lin Zhao to an imaginary world where human beings are not beasts, and where kindness and love is possible. Perhaps this illusion helped her withstand torture and inhuman living conditions, and enabled her to compose her writings in prison. The executioner’s bullet ended her life on April 29, 1968. Lin Zhao’s affront against the state also cost the lives of her parents. They committed suicide while she was in prison.

The story of Lin Zhao is not an anecdote about the People’s Republic’s irrational and confusing first years. Her restless ghost still haunts the land and the mind of the authorities. This vicious circle will not break so long as the government continues to persecute the innocent. The fear of final judgement will always stick to the perpetrators like their own shadows.