A Requiem for Adwa Victory

by Chalachew Tadesse / March 6, 2015 / No comments

The battle that secured Ethiopia’s independence occupies only a small role in the country’s pop culture, just as Ethiopian works are underplayed in African literature as a whole.

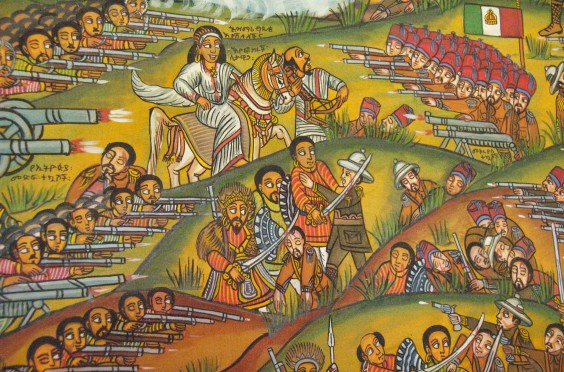

The Battle of Adwa was the first time an African nation defeated a European power. Photo via: Wikimedia Commons

In the United States, February is celebrated as Black History Month. But where was the real foundation of black freedom and dignity laid down first? It was at the Battle of Adwa, in northern Ethiopia, where Ethiopians fighting under Emperor Menelik II (who reigned from 1888-1913) and his consort, Empress Taitu, routed out the invincible Italian colonial army on March 1, 1896 (February 23, 1888 in Ethiopia’s Julian calendar). Interestingly, this defeat of European power came a decade after the shameful 1885 Scramble for Africa conference that carved up the African continent among European powers.

- This column’s topics will include literature, art, education, history, and political culture in Ethiopia, as well as society and politics in the Horn of Africa. Moreover, I will address the tribulations of journalists and the ill-fated constitutional right of freedom of expression under Ethiopia’s deceptive authoritarian regime. I will try to be the voice of the voiceless, be it persecuted journalists at home or exiled journalists abroad. These themes will make Ethiopia’s uniqueness and absurdities evident.

- Chalachew Tadesse is an Ethiopian journalist and columnist. He has previously worked as a full time journalist for The Reporter and The Sub-Saharan Informer English newspapers. He was also a columnist for the much-acclaimed Fact magazine, before the Ethiopian regime closed it in October 2014. A political science student by training, he works as a university lecturer and is known for his sociopolitical commentaries on the Ethiopian private press.

In essence, the Battle of Adwa was the first episode par excellence to usher in the ultimate demise of colonialism, Euro-centrism and white supremacy in Ethiopia. Above all, it is an essential reminder of mankind’s never-ending zeal for freedom. Adwa was also in effect the raison d’être for Ethiopia being the only independent nation in Africa. That is why it has a special place in Ethiopians’ psyches and collective memory.

I would, therefore, do disservice to the notion of freedom if I didn’t dwell on the Adwa victory and its representation in Ethiopia’s art in this March column. Alas, Adwa’s place in Ethiopian art — music, film, novels, and poetry — is scant, if not virtually non-existent.

Undoubtedly, the post-colonial Africa’s literature has thrived so profoundly that it has tried to rediscover the past and redefine the present. In contrast, Ethiopia’s literature has progressed at a snail’s pace. It is understandable that Ethiopia has made positive contributions to Africa as a whole (the victory at Adwa being only one), while occupying only a small role in African literature. One may erroneously attribute this to the fact that most Ethiopian literature is not written in English, but in Amharic, a language specific to Ethiopia.

But the fact remains that even for fiction and poetry composed in Amharic, several important themes are conspicuously absent from Ethiopian literature: Adwa’s timeless impact on Ethiopians’ identity and self-consciousness, the ethos of war and heroism, perceptions of dignity, resistance and freedom from alien rule, all of which, I presume, constitute integral parts of the Ethiopian psyche. Conversely, the paradox of freedom from colonialism vis-à-vis the perpetual lack of internal freedom, equality and justice has always been a quintessential Ethiopian absurdity. Strangely however, this paradox isn’t adequately reflected in the literature of our country.

Film Professor Haile Gerima’s documentary Adwa: An African Victory, which was produced and directed from an African perspective in the United States, is the only seminal Ethiopian English film that brought the Adwa victory to worldwide prominence. As far as I know, no other film of worldwide importance has ever been made on Adwa.

Music is no exception either. However, two seminal tracks by contemporary Ethiopian pop singers, Ejigayehu Shibabaw (aka Gigi) and Tewodros Kassahun (aka Teddy Afro), are worth mentioning. In her 2001 masterpiece track “Adwa” the world famous singer Gigi pays tribute to Adwa’s timeless significance:

The life given to me today in freedom

Martyred were men for it

In blood and flesh

How many countrymen fell

In the land of freedom

In her panoramic recollection Gigi emphasizes the worth of sacrifice and fierce resolve for the sake of freedom, dignity and national identity. And of course Ethiopians owe their forefathers a lot for their sacrifices.

Let Adwa speak up, let my country speak up

How I stand before you today

Day by day I live in pride, dignity, happiness, love

In triumph I live day by day

Gigi rightly reaffirms that Adwa has much bearing on the life of Ethiopians. In singing the words “How I stand before you today,” she is explicitly declaring that had it not been for Adwa, Ethiopians would not have been who they are now. Gigi also underlines that Adwa is a victory for both black people and Africa. She emphatically says: “Adwa, Africa, mother Ethiopia, tell your history of triumph.”

Widely hailed as Ethiopia’s own Fela Kuti and Bob Marley, Teddy Afro is a pop music superstar. In his 2012 track “Tikur Sew” (Black Man), he paid a captivating tribute to the heroism and legacy of Emperor Menelik. The music video for “Tikur Sew” offers an unparalleled, vivid reflection of the actual battle at Adwa as we know it from history books.

Come to Adwa ready to fight/defend

That Black King is there and

The spirit/zeal burned

Victory brought luck to the children of Africa

In essence, “Tikur Sew” portrays Menelik as a black anti-colonial hero par excellence, a symbol of freedom for all oppressed black people.

“Tikur Sew” also recollects the deeds of famous patriots drawn from most of Ethiopia’s ethnic groups. It seems that it is intended to counteract the narrative of the ruling Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which claims, in effect, that Adwa was only the victory of the Tigrayan ethnic group. Ironically, the Adwa province, which is populated by Tigrayans, is the birthplace of many of Ethiopia’s incumbent leaders, including the late dictator Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. Alas, the TPLF’s claim is a new Ethiopian absurdity hitherto unheard in the country’s long history.

So what? When the child called, what was said?

Yes!

If I had not said yes at that time

I would not have become who I am

Menelik Black Man

Unequivocally, “Tikur Sew” emphasizes that had forefathers said no to Menelik’s plea, Ethiopians wouldn’t have been who they are now. That is precisely true given the deep, enduring scar that colonialism left on colonized Africans. In part, that is why we Ethiopians, whether rightfully or wrongfully, boast about our “distinct identity” — a claim that other black Africans aren’t happy with.

Mind you, the hallmarks of Teddy’s lyrics consist of history, heroes, nationalism, unity and forgiveness. Conversely, Ethiopia’s ethnocratic and authoritarian regime is inherently hostile to these issues. Hence, Teddy is the only rebel singer whose songs are largely considered protest anthems, sung in response to nihilism, revisionism and the seeds of ethnic discord and disunity sown by the regime. Perhaps that may be why he was thrown to jail for two years in 2008, convicted of controversial charges. He also faces occasional travel bans.

Thanks to TPLF’s ethnic politics, ethnic Oromo (the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia) fanatical secessionists disparage Menelik’s internal legacy and Adwa’s significance. As a result, they wage a war of attrition against Teddy for glorifying Emperor Menelik, whom they label as a “black colonizer.” Ironically however, Teddy’s song also glorifies famous Oromo warriors at the battle of Adwa, thereby making Adwa an Ethiopia-wide victory. Above all, some of the lyrics for “Tikur Sew” lyrics are composed in the Oromiffa language of the Oromos, demonstrating the song’s unifying role.

Narrow ethnic fanaticism manifested its ugly face when Coca-Cola, a US-based company, had Teddy sing “The World Is Ours,” the anthem of the 2014 Brazil FIFA World Cup. Soon, some ethnic Oromo fanatics launched a viral anti-Teddy campaign and vowed to boycott Coca Cola’s products if the company released Teddy’s recorded version. Alas, Coca Cola gave in to the threat straightaway. Hence, Coca Cola poured cold water over both Teddy’s fame and Ethiopia’s golden chance to export its music.

Notwithstanding his trials and tribulations, Teddy has defiantly continued to sting the degenerating conscience of ethnic fanatics, Ethiopia’s leaders, and the seeds they sow.

Finally, I must emphasize that Ethiopia’s art needs serious soul searching to reflect the past and define the present. At the same time, I must underline that successive generations of Ethiopians have failed to translate the fruits of Adwa into new momentums and concrete actions to solve the country’s longstanding socio-political, historical and economic predicaments. This aside, it is undeniable that we Ethiopians would not have been who we are had it not been for Adwa and Menelik. And Adwa’s implication for today’s Ethiopia is this: freedom will prevail, sooner or later, over the current ethnic discord and pervasive repression. Viva Adwa! Viva Menelik!