Shelves in Exile

by Mesfin Negash / October 30, 2014 / No comments

The relationship between literature and its readers deepens in exile and isolation.

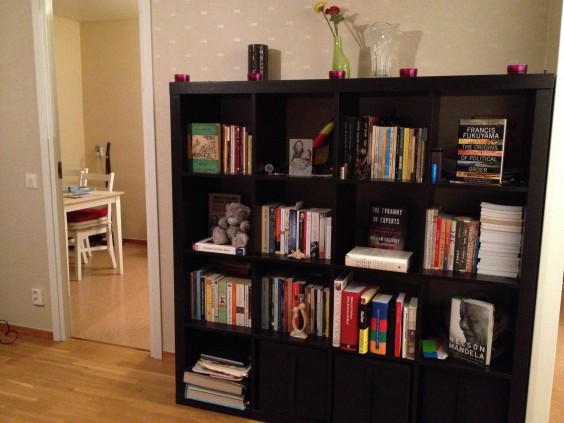

Mesfin Negash's own exiled shelf.

Much has been said about the relationship between man and book. Few other relationships last as long as the one between humans and books, I believe. Even where reading isn’t a part of popular culture, books are considered to be respected counsels for those fortunate enough to have them.

- Why does a country with her own unique alphabet and long history of writing persist to deny citizens the right to freedom of expression in this era of Expression? No other country in Africa may typify this paradox more than Ethiopia. As Leopold Senghor’s famous collection of poems entitled “Ethiopiques” remained ‘powerful and popular’ so does the source of his intriguing title, Ethiopia, in her own ways. In “Ethiopiques,” I share Ethiopian views on pertinent issues related to journalism, culture and, of course, the overarching subject of politics.

- Mesfin Negash is an Ethiopian journalist living in exile in Sweden. He is one of the journalists accused of “terrorism” in 2011 by the Ethiopian government, and later sentenced to 8 years prison in absentia. The co-founder and first editor-in-chief of an acclaimed Ethiopian newspaper, Addis Neger, he continued writing from exile. In addition to writing and engaging in public discourses, he is an ardent advocate of Freedom of Speech and the Press. He is a student of political science and journalism known for his critical commentaries on significant political and social issues in Ethiopia.

This relationship often deepens during the lowest points in life, as in prison or exile. People can hardly forget the books they read in prisons, hospitals, camps, or other places where they were far from their comforting social circles. I think the experience in exile is of the same nature. Exile causes both physical and spiritual detachment, whether one admits it or not. Therefore, it is only human to search for a means to reduce the impact of physical distance. Despite the blessings of the Internet, which makes real time connection part of everyday life, books from and about the homeland remain important links for exiles. In my experience, reading these books in my first language adds extra value.

My curiosity landed me in many occasions in wondering what my fellow refugees considered worthy of taking with them their last moments before fleeing. What do people carry with them at desperate times, especially when setting feet to the long journey into exile? There is no list of “things to take with you” to speak of but I suspect many reach for a book before they bid farewell to their closest friends and family. For some it might be a prayer or holy book; others might select a work of their favorite poet, novelist, or philosopher. Others might take the book they never had the chance to finish; a childhood favorite shouldn’t be ruled out, and so the list of possibilities goes on and on.

In retrospect, picking a few books for my long road was not problematic. A person can select by chance or choice. What turned out to be challenging was getting new books once “settled” in exile. One can’t help wondering what kind of books are on sale and which author is the most-read back home. To exiles, books are more than their literary values and content; they are routes into the zeitgeist. Unfortunately, I have encountered a few who consider this urge for new books a luxury.

That is not the end of the story. Often, finding a person who can buy and send books that are to one’s taste isn’t an easy task, not to mention increasingly expensive. Mailing books via post office is a prohibitive cost, and the same is true of the price tags on books from the homeland. Two of the shops in my city, Stockholm, sell books from Ethiopia at more than three times their cover prices. Therefore, finding people who are traveling between my homeland and “hostland” and convincing them to courier the books is the best option. There is a consolation here: many people find this an easy favor to do. Is that because people in general have a positive view about books? I don’t know.

Every time I see libraries in exiled homes, I think of all these intricacies. Each book on exiled shelves has a story besides the one between its covers: who bought it, and where, and when, and how it arrived in its current country. Some of the books might have travelled with their owner all the way from home, some purchased in the middle of the journey, some bought at home but sent later on.

The middlemen between the books and the exiled person also have their own story. Fortunately enough I have many generous and thoughtful friends, and there are few who outshine the others. They never care how much this transaction costs them as long as I get my books. Others add a humor in the exchange: one friend sent me a book both of us would have abhorred, provoking me to write. A book vendor from whom I used to buy books in Ethiopia also sent me books, free this time around. Some of my book-sending friends are in prison now. Five others have left Ethiopia for varying reasons. The good news is that as long as people love books, there won’t be lack of contacts to send and bring books to exiled shelves, the treasures of memory and undying connection.