Lolita in Kabul

by Yaghoub Yadali / October 2, 2014 / No comments

Does a new translation of the novel change the cultural exchange between Afghanistan and Iran?

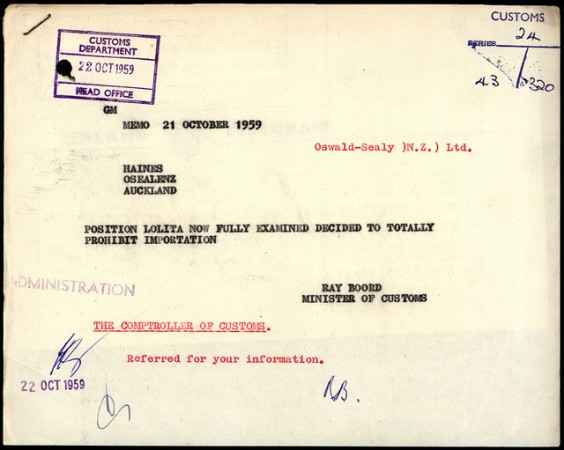

Lolita was banned in many countries, including Iran. photo via Flickr user: Archives New Zealand.

In 1953, Vladimir Nabokov finished writing Lolita, the story of a relationship between a middle-aged man and a twelve-year-old girl. Because of the novel’s controversial themes, Nabokov was not able to publish Lolita in the United States for many years. In 1955, Nabokov sold the novel to Olympia Press, a French publisher of erotic fiction and avant-garde literature. Lolita went unnoticed until novelist Graham Green called it one of the three best books of 1955, causing much controversy. Finally, after great struggle, Lolita was published in America in 1958 and instantly became a best seller. Today, critics know this work as one of the most important novels of the 20th century.

- “Enemy…terrorism…nuclear bomb…war.” These words are often used by American media to describe Iran. The image the media presents is often hazy, incomplete, and distorted. The political and military aspects of my country are covered mainly in a negative light.

- In Under Eastern Eyes (I have adopted the name from the novel Under Western Eyes by Joseph Conrad), I will write about those topics which American media either cannot or does not want to talk about. The emphasis will be on social and cultural aspects of Iran although, out of necessity, I will talk about politics, despite my despair.

- Yaghoub Yadali, born in 1970, is a writer and television director. His first work of fiction, the short-story collection Sketches in the Garden, was published in 1997. It was followed in 2001 by Probability of Merriment and Mooning, which was named book of the year by the Writers and Critics Award. His first novel, The Rituals of Restlessness, won the 2004 Golshiri Foundation Award for the best novel of the year and was named as one of the ten best novels of the decade by the Press Critics Award. He has also published many articles and reviews of literature and cinema in newspapers and magazines in Iran.

Before the Iranian Revolution in 1979, there was no limitation on publishing works like Lolita. Although the book was translated into Persian shortly after the American publication, it was not an accurate version. This year, six decades later, an Iranian translator has completed a new and comprehensive Persian translation of Lolita. Due to Iran’s censorship laws, it is not possible to publish Lolita in Iran. The Persian translation was published online, and and the translated book was published in Kabul, Afghanistan. In post-Taliban Afghanistan, writers are no longer required to send a copy of their book to a government agency for review prior to publication. This is a privilege that only a person who has experienced censorship can fully understand.

In a way, one can see the publication of Lolita in Afghanistan as mutually beneficial to both countries’ cultures. In Tajikistan and a big part of Afghanistan, people speak Persian; centuries ago, all three countries were one. Deep historical roots and a shared language facilitate literary exchanges between Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. Despite political differences, the three countries maintain a cultural relationship.

However, because of the potential for human growth and development in Iran, the literary exchange between countries has often been one sided. Many Iranian books on politics, science, history, and literature are sold in Afghanistan’s markets and met with enthusiasm by Afghan readers. Some Afghan romance and short story writers publish their books in Iran. As a matter of fact, in the last decade two books by the Afghan author Mohammad Asef Soltanzadeh have won the prestigious Golshiri Literary Award in Iran. For these reasons, Afghan bibliophiles usually have their eyes on original or translated books published in Iran. But this time, it is the Iranian bibliophiles who have to venture to the book market in Afghanistan for an up-to-date translation of Lolita.

These days, a copy of Lolita can easily be found among the merchandise of booksellers and street peddlers anywhere in Tehran. Perhaps that is a testament to the fact that limitations – no matter if they are imposed by governments, publishers, or moral groups, no matter if they are in Iran or in the West – will never prevent the publication of a genius work of literature.