The Leftover Monologues Premieres in Beijing

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / August 6, 2014 / No comments

China’s Unmarried Women Speak Out

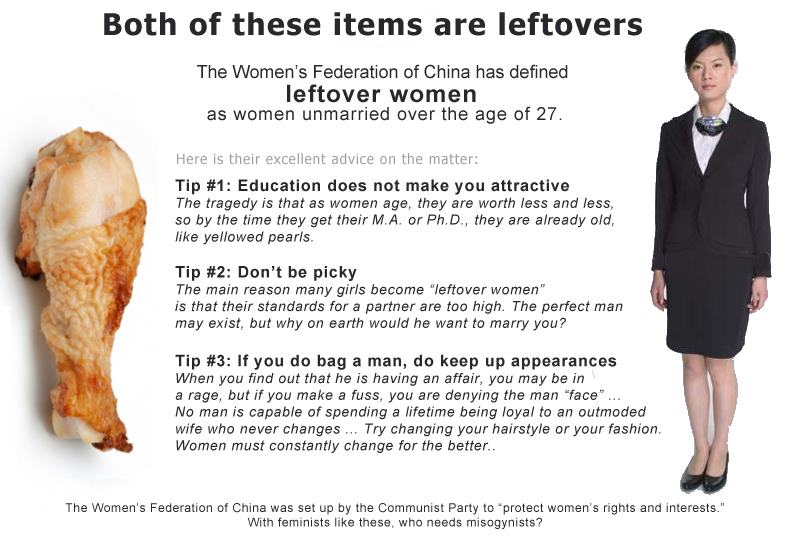

In 2007, the Chinese Ministry of Education published a list of 171 new words that have entered the nation’s vocabulary. Among them was the phrase “Sheng nu” or “leftover woman.”

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

There is indeed an increasing number of unmarried young women in urban China. The majority of these unmarried women are college-educated with high-paying careers. Generally, they are well-educated women with lavish metropolitan lifestyles. This type of woman may have a cat in her apartment but no husband. This phenomenon is partially a result of China’s rapid transfer to a consumer society in the last two decades.

In rural areas, the male to female ratio is 145:100. The population is predominately male, and the rate of kidnapped women and children being sold to unmarried male peasants on the rise. Meanwhile, in metropolitan areas, the longer a “leftover woman” waits to wed, the stronger familial/societal pressure weighs on her. A woman in her late twenties is already considered a “leftover” in Chinese society. A woman in her late thirties is deemed undesirable and has a severely diminished chance of finding a husband.

Traditionally, the Chinese employ arranged marriage. Because the family unit is of utmost importance in Chinese culture, a single man or woman is an anomaly. When a young person comes of age, his or her relatives are obliged to guide the lonely soul in search of their counterpart.

Today, government agencies have replaced the family as a matchmaker. In large cities, meetings between single men and women are arranged by a diverse assortment of organizations, including labor unions, women’s associations, the civil affairs office, and the youth league. In Shanghai, there is even a yearly marriage fair, where over ten thousand single men and women are offered the chance to seek out their future mate.

Roseann Lake, a Beijing-based American journalist, has interviewed more than 100 “leftover” women in the past two years to collect material for her book on this topic. The interviews have inspired her theater production The Leftover Monologues which provides unmarried women a stage to profess their thoughts on love, sex, and marriage.

Ms. Lake posted a casting call on the website for “Gender and Development in China”—

“At the end of July 2014, we’ll be staging China’s first-ever rendition of The Leftover Monologues. Structured similarly to The Vagina Monologues, (don’t worry if you’ve never heard of or seen that play), ours is a play uniting a dozen or so brazen Chinese (and foreign) voices in a stirring evening of entertainment and insight into the complexities of love, sex, marriage and relationships in China – with an emphasis on the unrealistic societal pressures/expectations that accompany all of the above.”

While the phenomenon of “leftover” women is not a taboo topic of conversation when discussed on an impersonal social level, exposing one’s intimate, internal life before an audience is certainly an unwelcome cause in the greater public’s eye. The Leftover Monologues has been adapted into five different renditions. It has been performed by theater students at ten universities in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Changsha. The tickets are always sold out, and the performances spark a sensational response from the audience.

Yet the social reality outside of universities is different. Chinese women are not truly liberated in their minds, and Chinese society allows very little space for progress on women’s issues to take seed.

Violence against women has a thousand faces in China—violence does not necessarily take the form of physical abuse. It is also engrained by the influence of Confucian orthodoxy and age-old social conventions. Discrimination against unmarried women is hidden under the guise of concern for a woman’s well-being. The thinly veiled intolerance of a woman’s independence creates enormous psychological stress for these “leftover” women. The name alone, “leftover,” or “sheng nu” means waste, redundancy. How can a woman feel valued when her title in society is an insult?

Marriage in today’s China suffers under the extremely materialist values of a post-Mao era. Many people marry to improve their living standard. A house, car and residency permit in a big city like Beijing or Shanghai are the minimum requirements for the coveted lifestyle. A woman who has worked her way through the university into a career often possesses these of her own accord. A husband’s role is then null and void for an educated woman.

Roseann Lake, having lived in China four years, has observed the matchmaking custom become obsolete for professional young women. She provides women an opportunity to share their monologue on the pressure to observe a demeaning social function.

One of the protagonists of The Leftover Monologues, Ms. Song, exposed that she has been pressured into paying 10,000 yuan to a marriage agency in order to find a husband with a yearly income of 500,000 yuan. But what of his character? Only his material assets count. The task of generating discussion on the plight of China’s newly emerging female professionals must fall on those working in the artistic sector, innovators like Roseann Lake.

The Leftover Monologues premiered on July 26 in a small Beijing theater. While it is unlikely that production will mark a turning point in the way Chinese society views unmarried, professional women, the production is a worthwhile social experiment.