A Nice Farce for the Pro-Revolution Middle Class

by Israel Centeno / July 16, 2014 / No comments

A brief history of nuevo trova music in Cuba.

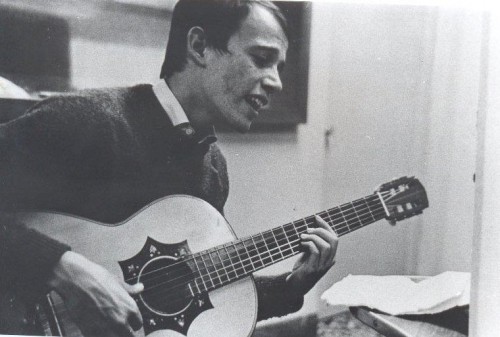

Silvio Rodriguez, 1968. Photo: Wikimedia.

“After a thousand failures like those, I felt really stupid:

They had deceived us, they had deceived us,

And I went in search of the first man who lied, who lied.”

—Silvio Rodríguez, “La primera mentira”

After bursting onto the subversive scene of the metropolises, with folk instruments and the ethnic provocation of the colonized, protest music was a bestseller in the consumer market, the cries and complaints, devoid of metaphor, as literal as their pamphlets, exposed their contradictions, and the new protest music sought to reinvent itself by clearly distancing itself from nationalism and socialist realism.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

The new wave of Latin America’s revolutionary singer-songwriters looked for the keys to their reinvention in capitalist counterculture, although this counterculture was closer to individualist anarchy or the utopias condemned by scientific materialism than to any kind of new attempt to take heaven by force and convert it into a socialist paradise. In this way, the Cuban nueva trova, among others, was born. Removed aesthetically and formally from the picturesque hymns of the proletarian revolution, the musicians sought to capture the poetic tone of the non-conformist American folk music typical of Bob Dylan or Joan Báez.

The nueva trova singers tried to institutionalize a landmark event. They wanted to become the true poetic and musical expression of the new man, born from the dialectics of the new society. They wanted their music to be nothing like the Caribbean sound prior to the revolution, which was, according to them, related to casinos and mafias; they wanted to have none of the guttural qualities of Carlos Puebla—far too cheerful and rudimentary for these socialist Beatles—and to have absolutely nothing to do with the incoherent instrumental explosion of cuatros, maracas, drums, charangos, quenas, and the atavistic lament of the world’s wretched.

The songwriters of nueva trova, members of communist youth groups, committed to constructing socialism and fighting for a classless society, put forward a proposal—a brand?—to be consumed by Cuba’s intellectual bureaucracy along with the middle and upper classes of the universal left.

Nueva trova would not be sung in the old Hilton to the fun-loving Havana bourgeoisie. No, it would be sung to the newly professional young people from legendary universities, products of the Nueva Escuela, trained as political and military officers to carry out wartime missions in Angola, Central America, Eritrea, and Granada. Consequently, it’s no accident that among the lyrics you find a blue unicorn in a Guatemalan or Salvadoran jungle. The Silvio Rodríguez song “The Pioneers” is hardly innocent either.

They would organize “civil” concerts in the squares and particularly in La Plaza de la Revolución. They would be the support act for the star that Fidel “dignified so it would shine on these lands” forever and always.

They didn’t neglect Cuban revolutionary tourism or the other important item in the party’s agenda—foreign currencies and the influx of hard currencies to the island.

Those ballads, with their overdose of pastoral epic, were the soundtrack to the 1979 Peruvian embassy crisis and the Mariel boatlift. Behind the scenes of the heroism about which songs were sung in the Special Period, the jineteras were putting on their makeup, and hunger and malnutrition were imposed as a sacrifice. Particular emphasis should be laid on the fact that while the world caterwauled along to “La Canción del Elegido,” “La Maza,” “La Familia,” and “La Propiedad Privada y El Amor,” the firing squads continued their percussion of gunfire. Dissidents, ordinary people who attempted escape, special agents (Tony de la Guardia), and the Heroes of the Republic who fought in the African wars all fell, unnoticed, to that rhythm.

Nowadays, it’s hard to maintain that the nueva trova movement was simply a spontaneous consequence of the musical and cultural dynamics of the revolution. Rather, the opposite is true: It was a planned, activist movement with a purpose defined by the Cuban communist party, a need to convert the bloody sounds of a nightmare revolution into a ballad with pretentious, symbolically dishonest lyrics.

The lyrics composed by the American counterculture focused on the search for peace, frank criticisms of war, anti-racism, withdrawing troops from Vietnam, and the fight for civil rights. Conversely, in Cuba, by employing plenty of affectation and manipulating slogans—peace is war, war is peace—the communist party’s folk musicians, or nueva trova, altered meanings in favor of Fidel’s despotism, the small, wicked David always surviving against the stupid, wicked Goliath, and the rotation of power among the cowboy presidents of the Philistine country. The nueva trova movement was a brainstorm comprising Fidel worship, a hotbed of legendary hymns about Che Guevara, Cuban warmongering, despotism set to a new rhythm, and the muting of the true non-conformist rhythms that were brewing on the island.

With their music, full of hope and promise for the future, the party’s tasters, the great brand for the middle-class revolutionaries of the well-to-do world, stripped away the rights of the average Joe Cuban day after day.

It was all a farce. A beautiful, polytonal, saccharine farce, chock-full of epic poetry and romanticism, middle-class grandiloquence and propaganda.

The gun of the future.