“In the beginning was the Word”

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / December 18, 2013 / No comments

On the fifth year of Liu Xiaobo’s imprisonment.

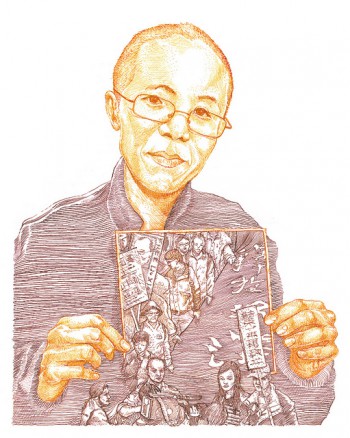

Liu Xia, wife of Liu Xiaobo. Image: Lunar New Year via Flickr.

Exactly five years ago, on December 6, 2008, Liu Xiaobo happily told me on Skype that there were already over 180 people who had co-signed Charter 08, an online manifesto for democracy and reform in China that he and his friend Zhang Zuhua initiated. “People are not afraid of the pressure, the signatures are still ongoing,” Liu said enthusiastically.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

“Xiaobo, you must be careful,” I said. “You know the old Party phrase: Shoot the bird that stretches its head out of the nest first.” I was worried.

“Hang on, there’s someone at the door. I’ll call you later,” Liu replied. Those were the last words I heard from him.

The scene that followed was dramatic. As the signatures on Charter 08 from inside China numbered 309, Xiaobo was arrested, and over Christmas the following year he was sentenced to 11 years in prison for “inciting subversion to state power.” Another year passed and Xiaobo received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, but an empty chair was placed on stage at the Oslo award ceremony to mark his absence. Meanwhile, the laureate was kept in prison in China. In addition, since the Nobel Prize was announced, Xiaobo’s wife Liu Xia has been kept under strict house arrest. Now her deep state of depression concerns friends as much as her husband’s condition in prison.

It is a difficult situation. Liu Xia urgently needs medical support, yet she dares not go to any government-assigned doctors, as they would send her to a psychiatric clinic where she could be lost forever, which happens to many other dissidents.

However, the Lius are not alone. This year, on the fifth anniversary of Liu Xiaobo’s arrest, there were multiple displays of solidarity for him and his wife around the world. There was a demonstration in Hong Kong appealing for Xiaobo’s freedom. PEN International asked for the immediate and unconditional release of both Lius. The Independent Chinese PEN Center, where Xiaobo formerly served as president, called for solidarity from all PEN chapters worldwide. Yet, the most interesting display was written by the human rights activist Zeng Jinyan, a friend of Liu Xia’s. On her blog, she published three demands for the Chinese authority:

1. Allow Liu Xia to visit a doctor of her own choosing.

2. Allow Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia to exchange correspondence freely; they should be allowed to read each other’s letters.

3. Allow Liu Xia to find work and earn her own living, as well as support her imprisoned brother’s child for schooling.

Zeng’s appeal shows the reality of Liu Xia’s incommunicado situation: Official physicians are taking care of a physically- and mentally-weakened Liu Xia. She has every reason to be suspicious that they are prioritizing party orders over her health. Furthermore, while it is true that Liu Xia can visit her husband once a month, their only form of contact with one another is eye-contact. Thick glass separates them. The conversation that they have through the attached phone is recorded by the prison warden. The only true form of communication the couple has is letter writing, but unfortunately the missives do not reach either recipient—instead they fall into the prison authority’s hands. Finally, it is to Liu Xia’s shame and disgust that the police buy food and other daily necessities for her, while her bank account is frozen and she has no money. Besides, she is not allowed to leave her home without police accompaniment. Liu Xia’s brother Liu Hui used to support her financially, but now he is also in prison. As a result, she is tortured with guilt.

Last December, when some friends sneaked behind the security guards and went to Liu Xia’s house for a short while, she broke into tears and whispered to her friend Xu Youyu: “My situation is as absurd as one of Kafka’s novels.” Now with her husband and brother both sentenced to 11 years in prison, her strength seems quite exhausted. No honor, no fame can help her. What she needs is a letter from her husband, hugs from her friends, and a walk free from police escorts.

The punitive measures made on a dissident’s family are absurd, yet not unknown in China. Aside from official tactics, family members are often discriminated at their jobs and children can be treated poorly in school. Under the Nazi regime Jews had to wear the Star of David; in ancient China, a criminal would be tattooed on the face; nowadays, there’re no such markings, yet the sword of Damocles and discrimination still hangs over the heads of dissidents and their family members.

In Liu Xiaobo’s criminal verdict, the court accused him of beginning “in 2005 to use the internet to post subversive articles.” It listed six of Xiaobo’s articles and Charter 08 as criminal evidence. Liu is a victim of the literary inquisition; he lost his freedom because of his words.

The Gospel of John (1:1) in the New Testament begins with the song:

“In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.”

The communists are atheists; they don’t believe in any god but themselves, yet they do understand the power of words. Condemning the words and their author is how they rule out all potential challenges to their absolute power. “Free Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia” and “Free the Word” are the world’s messages to the Chinese dictators. Word is thought, word is God, there is no way to cage or chain the word, and whoever tries to do so is destined to fail.