What Can You Say?

by Bina Shah / June 11, 2013 / No comments

In a conservative and increasingly violent Pakistan, writers struggle with self-censorship.

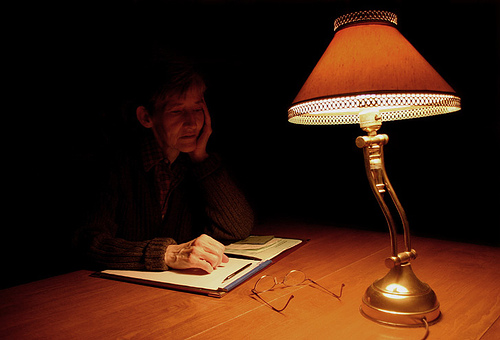

Photo: re_birf via Flickr.

I’ll never forget a conversation I had with a Web editor for a Pakistani newspaper at a bloggers’ meet-up one hot Karachi summer about two years ago. I’d been submitting blog posts to the newspaper’s online site for a year but we’d never met in person. When we did, over brunch arranged by the newspaper for all contributing bloggers, she fixed her wide eyes on me and said something astonishing: “Aren’t you worried you’re going to get shot because of what you write?”

- Pakistan is a country of contradictions – full of promise for growth, modernity and progress, yet shrouded by political, social and cultural issues that undermine its quest for identity and integrity. My bi-monthly column “Pakistan Unveiled” presents stories that showcase the Pakistani struggle for freedom of expression, an end to censorship, and a more open and balanced society.

- Bina Shah is a Karachi-based journalist and fiction writer and has taught writing at the university level. She is the author of four novels and two collections of short stories. She is a columnist for two major English-language newspapers in Pakistan, The Dawn and The Express Tribune, and she has contributed to international newspapers including The Independent, The Guardian, and The International Herald Tribune. She is an alumnus of the International Writers Workshop (IWP 2011).

I laughed, but inside I was startled. I’d never even thought of such a possibility. I wrote blog pieces that were provocative and that received a large amount of comments on the site, but getting shot for what I wrote was not anything I expected to happen to me. Yes, Pakistan has been listed among the most dangerous countries for journalists, many of whom are kidnapped, beaten, and sometimes killed, but I hardly wrote about the topics they covered: The activities of the military in Balochistan, the disappearance of Baloch separatists and intellectuals, the mysterious bodies that appeared in the desert months after people had been reported missing.

My subjects stay far away from politics. Instead I aim at Pakistani society, culture, and psychology. The most controversial blog I’ve ever written analyzed the actions of Egypt’s “nude blogger” Alia Al Mahdy from a feminist perspective, which earned me the title of “the blogger who supports nudity.” So far I’ve been called a “fake liberal,” a “feudal,” a “pseudo-feminist,” and a “West-lover,” but none of those epithets have ever made me fear for my life. Some of them have even made me laugh, once I had gotten done with grinding my teeth and hitting my head against the wall.

The editor’s question, which I found a little ridiculous, led me to think about a question not so ridiculous after all: What is it that you can and can’t say in Pakistan?

Pakistani writers tread a fine line when considering the issue of self-censorship in their work. The most obvious hot topics raise a red flag in any writer’s mind: Sex, particularly homosexuality, but also the portrayal of sex outside marriage; religion, particularly issues of blasphemy and minority rights; and politics, particularly the military’s activities in Balochistan and the government’s compliance with the United States on the drone attacks in Waziristan.

Different writers have different ways of dealing with these topics. Take sexuality. It’s impossible for a serious writer to utilize the silly euphemisms of Bollywood movies that portray lovers embracing and then cutting away to blooming flowers and burning fires. Instead, some Pakistani writers write about sex artistically, by portraying a sex scene with subtlety and finesse, rather than using graphic words to describe positions, acts, and body parts. Still others will use the director’s cut-away technique of leading up to a bedroom scene and then leaving the rest unsaid.

And some will deal with the issue head-on and damn the consequences: Mohammed Hanif in Our Lady of Alice Bhatti, speaks about a Christian nurse’s experiences with sexual harassment in a big city hospital, sparing no blushes and refusing to hide behind any veils of propriety, reminding me of celebrated writer Sadaat Hassan Manto’s similar stance. So far, nobody’s threatened his life for his openness, but it’s still a brave decision for a writer to take in today’s Pakistan, which is as conservative as in previous generations but more violent than ever before.

When living in a society that doesn’t appreciate freedom of expression and openness in matters of art it’s difficult to decide what approach will work to capture what the writer wants to express. Sometimes it’s better to respect society’s boundaries, and sometimes it’s important to break them. May the Lord give writers the wisdom to know the difference.