Virtual Reality Hunters

by Israel Centeno and translated by Kelly Harrison / April 9, 2013 / No comments

In searching for the limits of reality we find only boredom, violence, and homogenization.

Photo: Robin Hutton on Flickr.

I

There are those who expect a lot from reality—a revelation, a sign, or something through which they can carry out an aesthetic project—yet reality is something both inside and outside, a perception overburdened with different views, observed via our collective agreement and by means of various measures that make it “tangible.” In actuality, reality is probably not all that rich. Reality can also be read as a set of signifiers that are saturated with clichés and everyday expectations. We expect wealth and inspiration from it, and we question it in search of answers. And nothing happens. Little is said because it is repetitive, redundant, tiresome.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

With this I am reminded of Paul Auster’s Christmas story about a man who set up a camera opposite his shop and took a photo from the same spot every day for many years. Not surprisingly, the camera took the same photo time and time again, capturing nothing new, only a few qualitative details that nobody noticed. The photos didn’t reveal anything of importance or any instrumental changes, because there aren’t any, not even in excesses, crimes, war, attacks, rape, or assaults. You could take photos of every excess in the world and instead we would end up with photos of every inhibition: This is why we are so moved by trumpet fanfares and deeds of redemption. I cry out, “I can’t change my lackluster, unadventurous life, so I slap the world around and turn it all on its head. I may create a heaven or a hell, but at least I do something that drives away the taste of almonds or cyanide that is left in my mouth by the alienation to which my daily life condemns me.”

II

The theme of transgressions is a thorny one.

Nowadays, it would do me good to transgress, but how exactly?

Here be my dilemma. The Romantics were self-centered characters; all of them would certainly have read The Lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius; but in fact, if someone had reminded Lord Byron of Caligula’s or Nero’s excesses, it would have hindered the growth of the warts on his soul. He must have at least borne Gilles de Rais in mind.

III

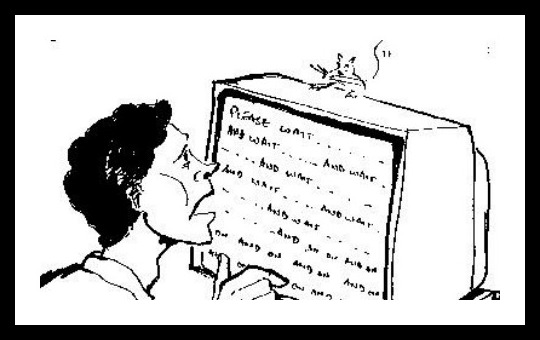

Sometimes, we surf the web fishing for astonishment, and only end up catching a cold from an all-nighter. Our searches are determined, we bait our hooks and nets and sometimes it’s an effort to reel in our fish: We enter sites that boast of their ease and originality, and after yawning loudly, we get the terrible sensation that ignorance has become democratized on social networks.

You can no longer talk about being excluded; the world of the intelligent is also the world of the ignorant. Or the people who blurt out the first thing that pops into their head. Or Google.

We view the innovators with enthusiasm: Those who think that they are leading the way in sexual insolence, those who discover the extremes of atrocity, the wickedness of man, the proximity of the end of the world, and those who enjoy themselves as if they were the last Goliards, the revelers in The Masque of the Red Death, even considering themselves to be like Giovanni Boccaccio’s characters. All without realizing that Giovanni Boccaccio was the author of The Decameron. This is where the saying by Umberto Eco comes in: “Memory serves not only to remember, but also to sort memories.” We are the creators of weapons of mass destruction, of concentration camps, and the reasons for hate. Above all, we are the creators of religions and truths and all the religions and truths for which it is supposedly worthwhile to sacrifice half of humanity.