Does Chávez Dream of Electric Sheep?

by Israel Centeno and translated by Kelly V. Harrison / February 26, 2013 / No comments

Philip K. Dick’s novel comes to life in this new Cuban-Venezuelan production.

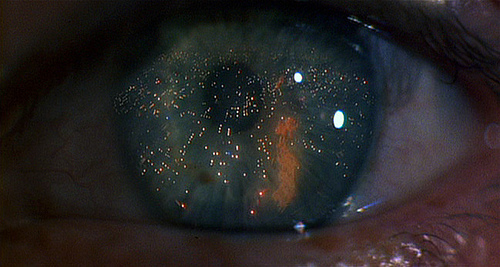

Photo still from Blade Runner. Photo: Dallas1200am. Creative Commons.

If there were any government that expected power to be exercised by digital replicants of its president, it would be the Bolivarian government. The agenda of a chaotic nation stems from an undisputed signature; orders and messages from the messianic entity are sent from the ether and carried out with meticulous punctuality; the Venezuelan patient’s seal of approval is able to make its way out of the intensive care unit and decree, for example, a currency devaluation or a land redistribution.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

All this makes me think of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dick’s novel, and its film version, Blade Runner, is a tragedy about humanized androids who refuse to accept that they have an expiration date.

In Venezuela’s case, it is not genetic engineering that has been employed to create someone to do the job of a president who has emigrated to an island. Unlike in Philip K. Dick’s work, the Cuban-Venezuelan version has created the android through political engineering and religious deceit.

Even activating Chávez’s constitutional mechanisms, Venezuela is unable to fill the absence of her ailing president. So she builds a robot to rule herself. Later down the line, this android ends up realizing the human Hugo Chávez’s ambition: it makes itself a god. Shall we go into Mercerism? This column is not long enough.

Better to go down the production route, not making a movie like Ridley Scott’s, but a soap opera co-produced and co-directed by the agents of power in Venezuela and Havana.

In Venezuela, truth doesn’t exist; there is but speculation and dogmas of faith.

Chávez, wired up or not, suffering, either in a coma or reading the Granma surrounded by his daughters, is no longer his own person. If this was reality, which it could well be, it would involve the hero being steered by his political engineers towards the culmination of his epic.

The light at the end of the tunnel approaches: there is cyber life after real life. And it doesn’t run out.

Hugo Chávez, or his android, drinks from a chalice in his garden of Gethsemane and rides the Cuban-Venezuelan melodrama; his avatar begins to display the omnipresence of his new divine reality. Will his life in the limbo of the absence of truth come to an end and? Having passed through that limbo, will he become a legend? Is he about to work wonders?

Now, after his return to Caracas, they would have to apply the Voigt-Kampff test, scan his retinas and consider, as political theory, that Chávez, a Nexus-6 with an expiration date, had been supplanted by a replicant with a sense of immortality and divine glory.

It is highly likely that in the next chapter, the android commander would neither die, expire, nor be cured, but attain immortality. He would be seated at the right hand of his Trinity, Bolívar-Liberator-Father, and would rule over his land. We could predict the words that the master android would utter to his apostles before ascending to glory: “Ramírez, Diosdado, Maduro: upon this army, this petro-state-PDVSA and this Party, I will build my church.” Then Chávez the miracle-worker would roam the chaotic earth and make the international left-wing groups speak in tongues. He would work wonders. Yet in the Cuban-Venezuelan version, Roy Batty’s masterful words—“All these moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain”—would never be heard, because Chávez, in this co-adaptation, is immortal.