Brave New World: Subtle Dictatorships, Pt. II

by Israel Centeno / January 29, 2013 / No comments

Huxley presents a startling vision of the future—or is it really the present?

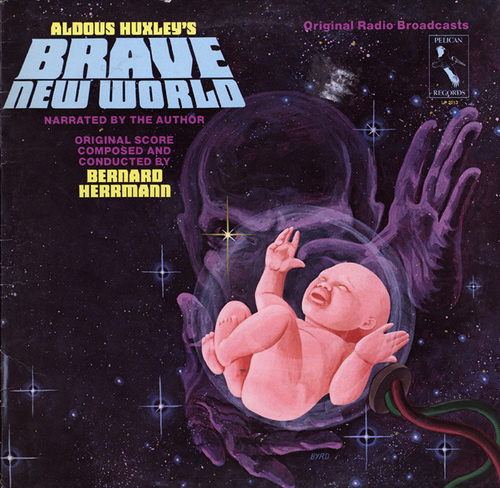

Cover art for the recording of a 1956 radio play of Brave New World. Photo: Matías Fernández, Flickr.

Below is part two of a series continuing the themes discussed in a previous series of articles concerning George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm. This section focuses on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and addresses the issue of a future without freedom, from subtle dictatorships to totalitarianism. Read part one.

In their search for answers about a society which has no room for questions, Bernard Marx and Lenina Crowne, the protagonists of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, decide to go to the savage reservation known as Malpais. Horrified, there they experience the religious rituals of a primitive culture that is free from the genetic and psychological conditioning of their perfect society. During one of these rites, they meet John, who invites them into his home. John lives with his mother, Linda, a “Beta” woman who, while on a trip with her friend, had an accident in Malpais and ended up living there against her will. Eventually Bernard and Lenina request permission from their superiors to return to London with Linda and John.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

In London, Linda is reunited with the soma she had been longing for and dies. John is introduced to the brave new world and finds ruptures and contradictions there. From his perspective, he is faced with human corruption, something of which the city’s inhabitants are ignorant as a result of their conditioned inability to ask questions. John the savage is living in a paradox: He finds it impossible to reconcile his freedom and previous values with the new genetically and psychologically conditioned reality. This leads to his meeting with the high controller of the system, Mustapha Mond, who puts forward detailed reasons and arguments for the values of the society that he leads. Eventually John moves away, deciding to isolate himself from society, while Bernard Marx becomes ever more content, having gained in social stature after introducing his friend, the savage, to civilized society.

After failing in his attempts to convince those around him that the values governing their society (consumerism, obedience, conformism, lack of intimacy, and the need for a drug to escape reality) are perverse, John ends up alone. Overwhelmed by powerlessness and desperation, he commits suicide.

In this novel, a refined, dystopic irony is constructed, at times very familiar to us as people of the 21st century. The scenario Huxley puts forth is more possible than the totalitarian nightmare foretold by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four. In both cases, man loses his freedom and the individual is divested of his own thought, judgment, and ability to choose. But in Brave New World, soma and the pleasure of consumerism creates the appearance of an ideal situation. The people made in the Hatchery and Conditioning Centre in London—and educated through hypnopaedia— connect being happy and satisfied with pleasurable sensations, yet they are never put in a position to choose, in a society that, as we continue reading, we are surprised to find is definitely possible and macabre.

In Brave New World, thinking does not play a part in daily life; the inhabitants are conditioned not to query anything. They are satisfied with their lot. They live in an imposed hierarchical caste system, yet they are happy with it and consider it normal. In this scenario, one could talk about biological and mental dictatorship. Instead of prisons and walls, consumerism and comfort are the restrictive criteria, without a doubt. Whether through genetics or through conditioning, the individual is stimulated and controlled in order to consistently provide the response most convenient to the system. It is a materialistic society, devoid of the idea of God—since God does not tie in with the scientific and technological advances of a world inhabited by superficial people—and almost devoid of the kind of spirit or humanity that we know today. It more closely resembles the inner workings of a giant, materialistic machine. Consequently, the notion of God is inadmissible, as the concept of spirituality would make the individual aware of what he is missing; questioning the world would mark the end of a reality ruled by a superior entity.

The mystic needs of the inhabitants of the brave new world are satisfied through the character of Ford, who represents science and its technical and psychological advances. By means of applied science, he, and not God, leads society to human salvation. Paradoxically, in this society, humans do not exist; humans are but a useful object for the advancement of science.

Brave New World, despite having been written in the interwar period of the last century, describes in vitro fertilization and a society driven and manipulated through psychological behaviorism, genetic biology, and drugs; it also details sterilization and the use of oral contraceptives, consumption as a means of attaining happiness, and the perfect drug that compensates for and provides pleasure.

This all makes for a terrifyingly familiar read. The concept of happiness and consumption being used as a substitute for freedom of action, coupled with superficiality and a lack of questions makes subtle dictatorships and happy submissiveness possible—something that we have been dealing with for some time now.