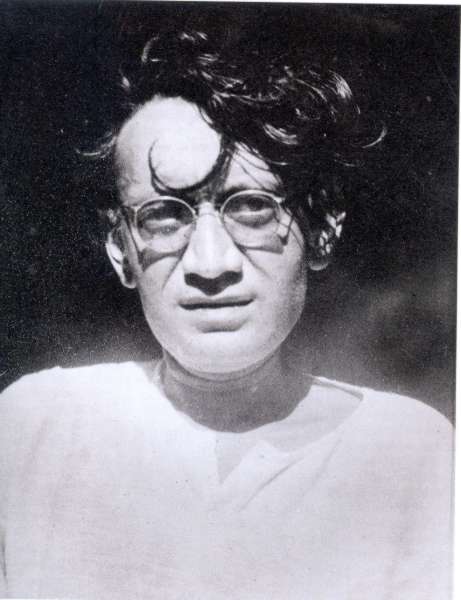

Manto: The Literary Voice of a Nation

by Bina Shah / September 4, 2012 / No comments

Fifty-seven years after his death Pakistani writer Saadat Hasan Manto is officially recognized

As Pakistan celebrated its 65th Independence Day, I began reading Mottled Dawn: Fifty Sketches and Stories of Partition, a recent edition of Pakistani writer Saadat Hasan Manto’s works. In 1947 Pakistan’s independence from Britain was a beautiful dream come true, but what followed was one of the bloodiest periods in both Pakistan and India’s histories, as the millions who left their homes to resettle in the new countries were ruthlessly slaughtered by militants in clashes on both sides of the border.

- Pakistan is a country of contradictions – full of promise for growth, modernity and progress, yet shrouded by political, social and cultural issues that undermine its quest for identity and integrity. My bi-monthly column “Pakistan Unveiled” presents stories that showcase the Pakistani struggle for freedom of expression, an end to censorship, and a more open and balanced society.

- Bina Shah is a Karachi-based journalist and fiction writer and has taught writing at the university level. She is the author of four novels and two collections of short stories. She is a columnist for two major English-language newspapers in Pakistan, The Dawn and The Express Tribune, and she has contributed to international newspapers including The Independent, The Guardian, and The International Herald Tribune. She is an alumnus of the International Writers Workshop (IWP 2011).

Manto, who emigrated to Lahore in 1948, chronicled these times. He turned an unflinching eye to the violence, hypocrisy, and betrayal of people who had lived side by side for centuries but were now mortal enemies because of where they fell along the religious divide. His masterpiece, “Toba Tek Singh” portrays a group of lunatics in a mental asylum waiting to be transferred to either India or Pakistan and being unable to deal with the massive transformation in their lives. “Khol Do” is the story of the brutal rapes that took place during Partition. Manto’s essays and political sketches, including “Jinnah Sahib,” and his book Letters to Uncle Sam were his attempts to make sense of the chaos and trauma that Partition created.

But Manto paid the price for his honesty. During his lifetime he was accused of writing stories that were “vulgar” and “obscene.” His willingness to tackle topics that were considered taboo, his dark humor in describing prostitutes and pimps, and his direct language when writing about the sexual subjugation of the subcontinent’s women (no doubt influenced by his lifetime friendship with the Indian writer Ismat Chugtai) brought him to court six times, though he was never convicted. However, his personal demons proved to be his undoing, as he sank into alcoholism and financial difficulties. He died penniless at the age of 42, leaving a wife and three daughters behind.

It took decades for Manto’s work to gain the appreciation that it truly deserves. His supporters, along with Indian and Pakistani publishers and critics, lobbied long and hard for him to be recognized as the literary voice of a nation. Finally, fifty-seven years after Manto’s death, the President of Pakistan posthumously awarded him with the Nishaan-e-Imtiaz, the highest civilian award, for his achievements in literature.

The Pakistani novelist Muhammed Hanif said that Manto would not have cared about this award, but the short story writer and novelist Aamer Hussein believes that Manto would have loved it and that the money would have helped him tremendously. Yet in today’s Pakistan, with our Supreme Court again attempting to define what is obscene, I have a feeling Manto would still cause problems for the Pakistani establishment by doing what he did best – writing stories that tell the truth about who and what we, as South Asians and Pakistanis, really are.