Let Me Finish

by Israel Centeno / June 19, 2012 / No comments

Our blundering quest for Paradise

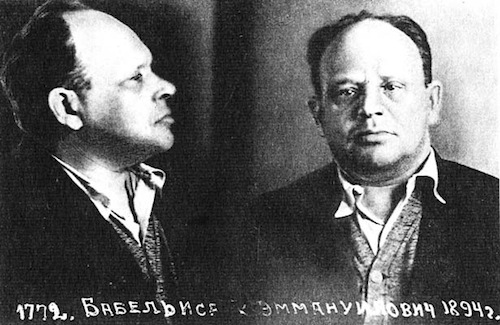

Halfway through the journey of building his own utopia, Isaak Babel, the author of Red Cavalry and Tales of Odessa (and, then, a new member of the Cheka*) said to a colleague, “I just like to have a sniff and see what death smells like.” Later on, perhaps horrified of, or foreshadowing the end of his journey, shortly before the death of his friend Maxim Gorky, Babel stopped writing, so as not to bow to the Creator. However, after this he ventured one further sentence: “I have mastered a new literary genre, the genre of silence.”

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

Everyone, at some point, has thought about or even longed for paradise. We associate it with a state of indescribable happiness. The ancient Persians imagined it to be like a perfect garden of eternal hunting, the wildlife indistinct amid a state of absolute innocence. The Bible defines it as the garden in which God placed his creatures in a state of total innocence.

Humanity, in its passage through history and via many archetypes, has recreated this notion of paradise. Individuals and civilizations have felt a tragic nostalgia for Arcadia and, having embarked on a quest to find it, have drifted off course.

Our sounds, rising from the evocation of innocence, bring the ambitions of our dreams to life: A limpid, untarnished future without pain, illness, misery, and bothersome contradictions. We hold onto the idea of perfect love and a fulfilling life. The Promised Land appears on the far side of an arid desert.

The asepsis of paradise, recently portrayed on social networks using the power of schmaltz, is obscene. An endlessly sunny day, serial and uniform in completeness, the absence of details, the non-existence of contradictions, happiness reified in faces full of divine serenity or in the throes of annoying orgasms. An exhibition in a catalog of illusions. Customary benevolence in a system where nothing is out of place or in conflict.

Yet the disgust at our own mortality, the anxiety that comes with knowing we are incomplete and the stress we experience when faced with doubt, makes us go to the ends of the Earth in search of absolute perfection. But, while looking to the future, we have been strewing the landscape with bodies. Those grand ideas that ensure the supremacy of something are creating new expressions of hate and cruelty.

Some perceive Paradise as an otherworldly place that we can reach after having carried out divine deeds, which are always cruel and painful. Others have tried to create paradise on Earth.

In the end, we are left with an ironic scene. Prior to being executed in 1939, an abandoned Isaak Babel managed to recapture a sense of happiness. After the torture and his confession, he regained the painful clarity of a mortal man, and remembered the phrase he uttered to Osip Mandelstam in a moment of pride: “I just like to have a sniff and see what death smells like.”

He then implored his executioners, before they fired the shot that would expel him from Eden, “Let me finish my work!” Perhaps he thought: An achievable paradise is in writing, in finishing my work.

*The first of many Soviet organizations concerned with military and political intelligence, founded by Felix Dzerzhinsky.

Translation: Kelly V. Harrison