The Innocents’ Club

by Israel Centeno / May 8, 2012 / No comments

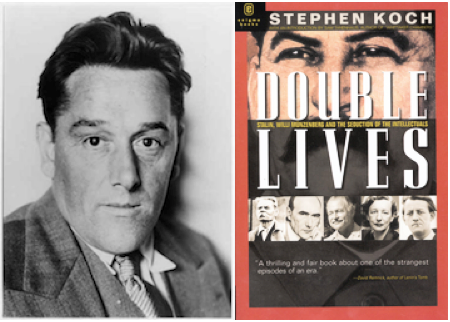

In his book Double Lives Stephen Koch writes a nonfiction account of the brilliant Willi Münzenberg and the double life he led while employed by the Soviet state. During his time Münzenberg was an advocate of the Kremlin and, according to the Spanish writer Antonio Muñoz Molina, if he had been born in the United States, he would have competed with Henry Ford. A child of the German working class with guts, ambition, and an enterprising spirit, he armed Stalin with an attractive propagandistic platform at his international festivals for peace and justice and built clubs of naïve intellectuals, known as Innocents’ Clubs, that secretly served the Soviet cause.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

But one day, after a restless sleep, he got the first call from Moscow, his greetings were unreturned, his friends were elusive, and finally he was expelled from the party. A trial began, they accused him of treachery, no one defended him, and no one saw the truth: Willi Münzenberg was brave, did not give in, and tried to overturn adversity.

In 1940 the German tanks were advancing on France and Münzenberg fled Paris. His body was found hanging from a branch in a wood. His comrades, who had promised an escape route, complied with Stalin’s secret plans and hanged him. No one saw his truth—not a single sympathizer with the antifascist cause, not a single promoter of freedom and justice for the people.

Like almost all Masters of Ceremonies of Stalinist totalitarianism, Münzenberg became a victim of his own conspiratorial machinery after completing his mission: Creating the values of the Left for the Soviet State.

While in exile, Leon Trotsky complained about those “friends” of the Soviet Union that Münzenberg had recruited into the Innocents’ Clubs. Trotsky defined their work as amateur journalism and accused them of lacking the strength to rebel against injustice in their own countries while always supporting faraway “revolutions.”

What Trotsky didn’t say is that, in his first exile, when he was planning the fight against the Tsarist autocracy, it was he who recruited Münzenberg and introduced him to Lenin. Together they assembled a major machine to recruit philosophers and Western celebrities by convincing them to support the revolution through humanist organizations. All humanitarian action was supposed to connect to the construction of socialism.

The years have passed and the corresponding avant-garde, humanitarian cliques still insist on sympathizing with the “good” despots. They have retained the old justifications and uncritical attitudes “in order to combat the Right.” As such, the ineffable effects of the Innocents’ Clubs still persist, along with their solidarity dance. They were faraway amateurs, as Trotsky said, part of a universal school of “radical tourists.”

Translation: Alex Higson