To Witness Unto Myself: An Interview with Jericho Brown

by Abigail Meinen / July 11, 2018 / No comments

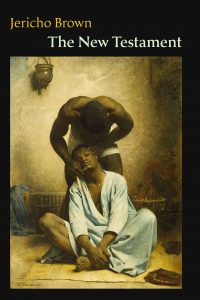

Image via Poetry Northwest.

Jericho Brown is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award and fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Brown’s first book, Please (New Issues 2008), won the American Book Award. His second book, The New Testament (Copper Canyon 2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and was named one of the best of the year by Library Journal, Coldfront, and the Academy of American Poets. His poems have appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The New Republic, Buzzfeed, and The Pushcart Prize Anthology.

Brown grew up in Louisiana and worked as a speechwriter for the Mayor of New Orleans before earning his PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Houston. He also holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of New Orleans and graduated magna cum laude from Dillard University. Brown is the director of the Creative Writing Program at Emory University and lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Brown visited City of Asylum in September of 2017 to read as part of the annual Jazz Poetry Festival. He talked with Sampsonia Way about his childhood in the Evangelical church, and how he sees ideas of testament, witness. and memory unfolding in his work.

Earlier today we were talking in the City of Asylum offices about your book and I said to someone, It’s that book with the gorgeous painting on the cover. I love this image on the cover and I was wondering if you could start by talking a bit about that.

It’s from a painting called The Barber of Suez by Léon Bonnat. And for a long time I thought it was the only time he had painted black people, but since then I’ve found other pieces that included black people. I love it so much because, in the 19th century, you don’t imagine people– especially people who are not black– thinking about black people as whole beings capable of introspection and feeling. It still seems hard for us to think about that now in the 21st century for some reason, at least for some people.

But I love the fact that the painting itself has so much tenderness, that at the same time it has so much brutality- there is so much risk involved in the very act of the shave itself. And there is something going on with the two figures that is so intimate, and yet so violent at the same time, and I’m really interested in that intersection. Where does intimacy and tenderness intersect with brutality and violence? And at that intersection is where I often find my poems. So I was really taken when I saw it, because that book is a book that’s so much about a masculinity and relationships between men. Relationships between brothers, relationships in particular between black men. I really needed that painting to be the cover of the book.

It’s funny how it came, too, because the book had already been taken by Copper Canyon Press, and they were in the process of designing the book cover before I even knew about the painting, and somebody sent it to me. It’s really funny, a good friend actually, the poet Lamar Wilson, sent me an image of it and he said, This is just like your poems. And I looked– you know, I clicked the image to see what he’s talking about– and I said, Oh my god, it really is just like my poems!

So I called Copper Canyon and my editor– his name Michael Wiegers– I said, Michael, literally hold the presses, like, you have to see this. And he said, I don’t know, Jericho, we’re already in the process. It’s really doubtful that we’ll be able… I’ll look at it, but I’m telling you… And I sent it to him and he called me back and said, Oh, yeah, I see. [Laughs] So all around it had support. All around. I was very pleased to have it as a cover. It makes me happy.

Absolutely, it’s all of those things you’re describing. And then the title, The New Testament. Personally, as a queer person raised in the church, it’s a fantastic title to encounter in a book of poetry. Can you talk a little bit about your background, how you brought the Biblical images into the book, and where that draw towards those images is for you?

Well, when I was growing up, I grew up in a very religious household. You know, I always joke that those people we make fun of, who watch Fox News, those people who are fundamentalists, Evangelicals, those people are my family, my parents. We went to church every Sunday, every Wednesday night, and everyday that there was a rehearsal for the ushers or the choir or whatever else there may have been. I think a lot of people don’t understand how huge church really is in people’s lives. There are so many auxiliaries that it can become its own world. You can be in a church and be on the drill team, or be on the debate team, or be on the quiz bowl. There are all these ways that it really makes its own world, and I grew up in that world. And I think, as poet, that kind of a growing up has been of use to me because ultimately, it was text-based. There was the Bible, and the Bible was full of music, and it was full of stories and, in all the work that I’ve done, that’s what I’m interested in. I’m interested in the music of language and how that music can intersect with a saying, with a story, with a telling, with some kind of a narrative quality, whether or not that narrative quality be completely known to us while we’re reading the poem.

I think what’s wonderful is you gain that perspective, but you also mentioned being queer. I think being any kind of marginalized person in this culture, it puts you in a position where you’re automatically skeptical. You’re automatically asking questions about things that are handed to you because you’re concerned that you are indeed getting an unfair deal. You become so acquainted with and so accustomed to the unfair deal that no matter what is in front of you, you’re looking for the part of it that’s unfair, that you’re going to have to deal with.

So, I think when I started realizing certain things about myself, I also had to figure out what that meant for this entire part of my life when I had been dedicated to a church that wouldn’t want me as I am, to a Bible that I still found myself reciting verses from when I got sick. What does it mean? How do I intersect that being who I am and who I was, with this being who I am and who I will be? And that’s why writing these poems became very important to me. It’s so funny, Genesis opens with what Gods says and when God says something, it comes to be. And then there was, you know? Even in John’s gospel- In the beginning there was the word. And so for me it became very important to re-inscribe myself into that language, that music, that I grew to love when I was a kid and also to invent and reinvent. And I believe we do that with poems.

Poems are all about facing some truth that we don’t realize we believe. That’s what I love about writing. I mean the real process of writing. You know you’re writing when you say something and you have no idea whether or not you really think that.[Laughs] Because you’re so caught up in the music of language that the next line just comes out, and you want to figure out: Well, I said that. It came out of my body, out of my mouth, out of this pen that I am holding, right? So what does that have to do with me? Then you have to stand next to what you’ve said and you have to become what you’ve said, whether you like it or not.

Poems are all about facing some truth that we don’t realize we believe.

So I was really interested in writing the book because I thought- Oh this will let me know who I am as a spiritual being. I needed to decide that for myself. And I think that’s actually very key to all of us. We can’t really allow other people, whether it’s family, whether it’s church, whether it’s just a friend, we can’t allow them to tell us who we are, particularly our spiritual beings. We have to make some decisions about that, and if you have a God that you believe in, it’s a good idea to have a God that also believes in you.

Thinking about the word and the idea of testament and testimony, and how that relates to story telling: there’s this conversation that, you know, if the oppressed and the marginalized just tell our stories and show people our pain and joy and our general humanness, then we become more relatable, sympathetic characters to the powers that be, and our oppression becomes less possible. You said something, when you were on a panel for #BlackPoetsSpeakOut, that I think about all the time. I don’t have the exact quote but it was along the lines of- I write these stories and I tell you, the reader, about myself- that I like ice cream and that I’m gay, but you don’t have to know those things about me to assume my humanity. I think that concept of assuming someone’s humanity rather than expecting them to make you feel or remember that they are human is really important when we ask ourselves- What is the goal of sharing these very vulnerable pieces of ourselves through poetry or storytelling? I wondered if you could talk a little bit more about that. What does testimony and testament mean to you in your work?

Well, when I think about testimony, I think about testament, and when I think about witness, I think about doing those things unto myself. I don’t really think about an audience for those things. I do not write the stories of my life, I do not allow personal experiences into my poems only so a reader can then understand that I am a human being and that those who are like me are also human beings. That might indeed happen, but that is not my goal, because I would like for people to be smarter than that. I would like for people to imagine my wholeness without me having to tell them about how I grew up. I don’t think how I grew up is so much different than how anybody else grew up. No matter how horrific it was, everybody has got a horrific story about how they grew up. I have the power of language. That’s my gift, that’s my talent. I can’t sing, but I can make a sentence, and therefore something about my growing up might seem different, because I write it in the sentences that I make, but in actuality, it’s just like anybody else’s growing up.

…if you have a God that you believe in, it’s a good idea to have a God that also believes in you.

When I write those things though, I write them because a memory uncovered is me getting closer to myself whole, myself human. When I can remember everything, I get it down and properly characterize it, I can see it for what it is, and what it means for me today. I can see it for how it reshapes itself into the man that I am now. And that’s what is happening when I’m writing a poem. What is not happening is me proving myself to someone else. I think witness, testimony, these things are very important in our poems, but I also think that when you write, they have to be on the same level as everything else.

The memory, the something that happened when you were a child, is just like a fact that you know from Wikipedia. Is just like your memory of the feeling of a shoe string that you held in your hand once. Is just like anything else. And while we’re writing our poems, any one of these things may need to seep into, seep through, come in. And, in the poet’s mind at least, there can’t be some hierarchy of values for material because you never know which juxtaposition leads to clarity. So while I do think being able to make use of one’s own life in a poem is important, I don’t think that’s the only material of poetry.

I think science, for instance, is a material for poetry. I think the very ground we walk on and the fact that the Earth is changing in front of our faces and deteriorating, I think that’s a fact for poems. That’s material for poetry. But just as much I believe that, I believe, you know, the love we made last night, the person we are in love with, that’s material for our work. But we have to be aware of all of those things if we’re poets. In the act of writing, any one of those things is of use to us. Every one of those things is of use to us.

As you’re talking about memory and childhood, and the things that you write about, I think there’s this question with testimony and memory like- did you get it right? Like- do you remember it right? Is this the right way to frame this thing? Do you grapple with that question at all? How do you think about, the “rightness,” and the “factness,” of memories?

Well rightness and factness seem to me two different things. I don’t expect that my memories will be exact. When I touch this surface, when I touch this door, and you touch this surface, you touch this door, we assume we’re feeling the same thing, but we will never know. I don’t know what you feel when you feel this surface. Do you know what I mean? I only imagine that, it must be as cold to you as it is to me. It must be as hard to you as it is to me. But I don’t know that. Do you know what I mean? And memory works the same way. When you have an experience, particularly when you have an experience with another person, what they see and feel and hear and know and remember, will be very different from what you remember, in spite of the fact that you’re both in the same place at the same time. So I don’t expect to get it right, and I don’t expect to get it exact. I don’t tear my hair out about fact, I tear my hair out about truth. I tear my hair out about whether or not I’m seeing the character of myself properly, much more than trying to see myself properly.

When I’m writing a poem and there’s a speaker in the poem that has a lot in common with me, I don’t assume that he is me. I know him to be a facet of myself. I know him to be a character. And he has access to everything that I have access to, but he’s not Jericho Brown at every moment. When a poem is done, it has its tones, and hopefully a poem will have several tones in it, but no poem will carry everything you’ve ever felt. That’s why you have to write a lot of them! ‘Cause you keep trying to get at every one of your feelings over time.

So I don’t think I worry about the fact of a thing, but I do get concerned about the rightness of a thing. I do get concerned about whether or not I have been ethical in certain ways. And by that, I don’t mean necessarily that I’ve been fair to people in my poems. And I don’t mean that I worry that I’m going to say something offensive in my poems. I mean, to be quite honest, I hope I say something offensive in my poems, I hope I say something that makes people uncomfortable. If people aren’t uncomfortable, I don’t know why I wrote the poem, you know what I mean? I want people moved, or I want people itching. [Laughs] Those are the two options.

I don’t tear my hair out about fact, I tear my hair out about truth. I tear my hair out about whether or not I’m seeing the character of myself properly, much more than trying to see myself properly.

But sometimes I do get concerned about whether or not I really am following all of the rules I’ve set up for myself. Sometimes when I’m writing a poem, I’ll decide, Oh I want the lines to be this long or I’ll want rhymes at the end of every other line. But I’m not talking about those rules. I’m talking about these larger guidelines I’ve set up for myself to be completely vulnerable to the poem. To simply allow it to have its life without me trying to take it over so that Jericho Brown looks good at the end of it. To not try to see myself as some sort of a saint or freedom fighter, and if the poem does some saintly work, if the poem does some freedom fighting, then I allow that to happen, but I also get to live my life where I make mistakes and I’m not so hard on myself because I’m supposed to be super poet. For me, that’s where I start having questions about rightness and where I’m ethical. We talk about using personal experiences in poems, but even to this day, there are poems that I think are really fine poems, but I don’t know that I would read them anywhere and everywhere. Is that okay? Does that mean I’m where I’m supposed to be if I know there is work that’s good work, but I get somewhere, and I can’t say it out loud? And I think that’s a question I have to ask, and that’s a question I have to answer. So when I think about rightness, that’s what I’m thinking about.