I am Legion: An Interview with Eileen Myles

by Abigail Meinen / June 22, 2018 / No comments

Eileen Myles. Photo by Peggy Obrien.

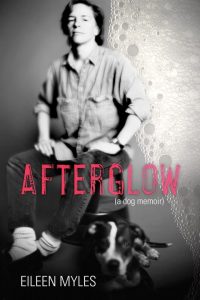

Each copy of Eileen Myles’ latest book, Afterglow, is covered in foam. It creeps over the corner of the front cover, each cell of air lined in light and shadow. “Writing (it is my belief) is sort of a performance and text and ideas and bubbles are always frothing & coming right until the last minute,” Myles writes.

Myles themselves is a multiplicity, and their writing foams, churns with currents, flows across the genres of fiction, memoir, poetry, manifesto. Afterglow, which Myles describes as a “punk dog book,” is a harrowing look at the death of their dog, Rosie, and the reflections that came after. It joins a list of over twenty books, including Cool for You, I Must Be Living Twice/new and selected poems, and Chelsea Girls.

Eileen Myles has been a salient voice in American poetry and queer culture since their time with the Saint Marks Poetry Project in New York throughout the 1970s and 80s. They are the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in non-fiction, an Andy Warhol/Creative Capital art writers’ grant, four Lambda Book Awards, the Shelley Prize from the PSA, were named to the Slate/Whiting Second Novel List in 2015, and received a poetry award from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. In 2016, they received a Creative Capital grant and the Clark Prize for excellence in art writing. They live in Marfa, TX and New York.

Myles visited City of Asylum in October of 2017 to read from Afterglow. They talked with Sampsonia Way about their gender, their Catholic background, and the ways that having a dog influenced their writing.

As a young, queer writer reading a book like this, I thought a lot about the word permission. I think books like this– that narrate all the not glamorous parts of writing– give younger writers permission to write about things they otherwise might not. To say- I had a shitty night, but I can write about it, and that’s okay. I was curious about where your sense of confidence and belief in the stories came from. Where did that permission come from for you? Did you feel like you needed it at all?

It’s funny, the word “permission” didn’t exist for me for a long time. I remember being at a reading in New York by Jim Carroll– I don’t know if you know this guy, Basketball Diaries was his big book. We were the same age, and at the time, he was the much more well known writer, so he was the guy who got what we all wanted to get really young– he was like a teen poet. So anyway, he did this reading. He’s Catholic, and I come from a Catholic background too, so we had some cultural resemblances. At the beginning of the reading, he did this funny sort of genuflect-altar-boy-thing towards the audience, and he said, I just need permission; I am asking permission. And I was just rocked. First of all, I never thought about the need for permission, and yet I knew that it actually was a huge thing for me, structurally. I think when I was in college, and I was starting to write, I would be in writing workshops, and it did feel kind of like a male/female split, because there would be these guys who were reading out loud in class, and they were reading what was considered to be kind of terrible poems, but they felt completely comfortable that they were poets and that this was just kind of their natural right.

I remember thinking, How does one get there? I felt like I needed to be crowned or given permission. I mean, that was the thing that felt like it was lacking for me in a certain way, but it did come, and I did get it, and in a way, it was sort of invisible. I think there was the first time I ever wrote a poem that I knew was good. I just knew it on such a bodily level. I didn’t have to ask somebody; I knew that was a good one, and it changed everything, that moment. And also, like getting to New York and going to parties… and I grew up in Boston and people would say, How are you? or, What have you been doing? They don’t say, What do you do? and in New York they would say, What do you do? and I would say, I’m a poet and then you would get a little grilled maybe. I always felt a little nervous, like someone was going to say, Oh come on. You know? And then again it just naturalized at a certain point. But it naturalized, I think, through community most of all. Everything came through community for me. There were certainly more bookstores in the 70s and 80s than any other time in my life since then, and there was always poetry there, and there was always a rack, but there were always the same magazines. That was my idea of getting published initially. There was a magazine called Kayak, there was a magazine called Caterpillar. I mean, if you were my age, you would laugh, because we all saw those magazines, and we all sent our poems to those magazines, as well as to the New Yorker and whatever. They would of course send you a rejection slip, and that would be it. It wasn’t until I started to get involved with Saint Mark’s Poetry Project and being in workshops there with people who were my peers, that I started to get that everyone was doing poetry.

In the 70s at least, the equivalent of being in a band was to have a magazine. Every poet had a magazine. The generation older than us, even if there was only one issue, all had a magazine. Every famous poet at some point had a magazine. It was part of a legend, that their magazine was called this or that. So you know, the guy next to me in workshop would ask me for a particular poem (and they weren’t even necessarily the best poems). I thought, Oh, it happens like that. Again, there’s so much class in there, too, because I came from a working class background, and since I didn’t know how things happened, I disdained the idea of things happening through people you knew. That seemed like nepotism or something, that the work was driven by or for rich people among middle class people. It took me a whole long while to get that the way things happened were through proximity and community and friendship and relationship, and that artists weren’t those people who were “out there,” those people that you mail your box tops into; they were the people sitting here with you.

So, I think it just came in a very organic way. I started to read with people, do open mics, get my work published by friends, and then realized I needed to do a magazine. And I did like two issues, almost three, in a magazine and realized how you could construct a community through activity. Proximity is the thing I always think about it; it’s spacial.

Afterglow by Eileen Myles.

I am really curious about what you have seen, particularly in terms of changes language, from your generation into the present. I am thinking about language in and of the queer community, and realizing that even the term “queer” is a very generationally loaded word. You are using they/them pronouns now?

Sure.

Is that something new for you or is that something that you adopted long ago?

Well, it seems like a recent opportunity to make manifest something that was true. I entered into this usage in the same way that I often enter into things, which was sort of sniffing and sort of suspicious. I had actually been interviewed for a profile on somebody else, on somebody I was dating, and they said, How do you feel about they, and I kind of said, Well, you know it’s not really intuitive, and you know… But there was this accident of language, which was that I had very recently heard– reheard– this story that I had grown up with which was Biblical. Supposedly Jesus Christ was going to exorcise somebody, and what you do when you exorcise demons from someone is you ask the demon their name, and the demon said, My name is Legion. I was like, Wait a second, my name is Legion. That means I am plural, you know? Then I started to think about they, how it contains multitudes, and my sense of myself. I feel like a gender knot or something. I feel male, and I feel female. I feel queer. I feel trans. I feel I’m a dyke, I’m a lesbian. I feel like a fag sometimes. It’s very mobile, and they really seems to hold that. And I also really love that I’m in my sixties, and of course certain people transition at all points in their life, but I don’t know anybody my age who’s changed their pronouns. I feel really happy that I can claim that, that I can do that. It feels like a mark I’m delighted to hold, and say Fuck you, if you don’t like it.

It took me a whole long while to get that the way things happened were through proximity and community and friendship and relationship, and that artists weren’t those people who were “out there,” those people that you mail your box tops into; they were the people sitting here with you.

So much of the backlash is that it’s not grammatical, or that it’s too hard to remember to use they for someone.

Right. Well the grammar is very interesting, I know. I got interviewed for Rolling Stone and this publisher, was using they, but they were using they is. They made it singular. First they didn’t use it at all, and then they did it wrong, and then I even got introduced publicly at the first reading on this tour, they is because it was a straight guy who was introducing the event. It seemed to him that he was using direct English. But I think the funniest thing about they, which I really enjoy, is that, as somebody who has been queer for a while, there always were times when you didn’t really want to tell somebody your sexual orientation, and so they’d say, Is your partner coming? Are you dating anybody? and I’d say, Yes. And they’d say, Well, are they coming? and I said, They are. You’d just keep the they up. What I think is so funny is I feel… I am in a closeted relationship with myself. There’s something sort of ludicrously beautiful, that I am still in the privacy of my gay couple. But again, it’s plural. I’m a relationship.

And my gender is none of your business. A while ago there was something I had to fill out at the gym, and there was a spot for gender, and it was the first time I wrote “X”. I thought, It feels good. I don’t think it’s anybody’s business, my gender. I mean, certain people will sign freely and do, but as far as having to give it up, I don’t think I need to.

I think of people like you and C. A. Conrad, who have been performing and expressing gender in a way that is very non-binary, or genderqueer. Now the queer community is starting to develop this new lexicon, whereas in the past these identities that we now call trans or non-binary would be “dyke” or like “sissy boy” or whatever.

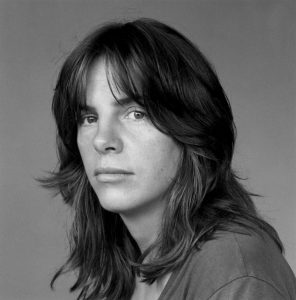

Myles in 1980. Photo by Robert Maplethorpe.

And for the generation before me it was a nelly queer or a militant lesbian.

All these identifiers are shifting, and I am wondering about your thoughts on that.

You know, I wouldn’t say I’m non-binary. Somehow it has a technical air, so somehow I don’t feel comfortable with that or claim that. It’s like shirts; If I could only own every shirt I’ve ever had, like I’ve had some amazing clothes, and I have small apartment so, it gets emotional too. You figure, you gotta put that whole period of time behind you, so you get rid of all those clothes. But I feel like in writing styles I can take back any writing style I’ve used. I can write a poem in my 70s style. It’s not like I have to grow past that.

I remember a few years ago, you’d be sitting with somebody, having coffee, and I’d say Yeah, we’re lesbians, and the person I’d be sitting with would go, Sorry, I don’t consider myself a lesbian. It happened more than once. I don’t do that. I feel like I don’t want to deny that word because it’s not that it ever was right, it was what was available. I’m still what flowed through the use of that word. So, it’s fine. I think the thing I’m most uncomfortable with now is the glibness. There’s a way in the queer community where lesbian equals terf. It’s loaded. I went to a TRANSparent conference in Rochester last December, and that idea was just thrown in in a very comfortable way, which meant that the lesbian had been banned from our vocabulary, and if you claim it, you’re aligning yourself with a transphobic position. Even the way Michfest was portrayed in the show- even though I was a part of the show and the way it was described– TRANSparent was not accurate, because what wasn’t there was the struggles. I never went to Michfest, but there were struggles that people went through around those issues, and they did get to a place where it was open, but that didn’t serve the plot line of the show. I felt like it did some real damage, and think it gave a generation who had less history about these things an opportunity to somehow condemn. I felt sad about that.

I feel like a gender knot or something. I feel male, and I feel female. I feel queer. I feel trans. I feel I’m a dyke, I’m a lesbian. I feel like a fag sometimes.

You mentioned a bit earlier that you raised in a Catholic family, what parts of Catholicism do you feel like you have held onto, or that have held onto you?

I think the excess. The Catholic Church’s incredible excess, and its really wild symbolism, and its ritual. I think there is so much. Even its repression is something that I worked through, and that I know. Sometimes, I think repression is a part of language, that there’s always something unspoken in a poem that is organizing it as it’s coming into language, and it may not come into language in this poem, but it’s still part of the absences and presences and the syntax. There was so much silence in my education, in my family. There was no discourse. So, I feel like I have a life devoted to what wasn’t there. I’m still fascinated and horrified by the ways and the times in which I still get paralyzed, unexpectedly, and I can’t speak. I try to honor it. I try to notice it, and let it happen. Like when I speak publicly, I find that sometimes my thoughts just kind of… An early computer would have these conflicts where it would be stuck, and my brain does that, you know? I feel like I’ve grown comfortable with public speaking, that I can just allow myself to be silent in front of an audience for a few minutes, until I get to what I meant to say or just let the moment pass, like a knot of feeling and expression. So I think, in many ways, I’m Catholic through and through. It’s still a very emotional part of me. Part of the thing that is strange about coming from that background is that when were developing, when you were growing, you didn’t know what was being said and being unsaid. There were things that were so obvious but a lot that wasn’t.

I was at a Catholic church for another purpose in the mid-80s at the height of the AIDS crisis, when the archbishop of New York decided that the gay, Catholic group, Dignity, could no longer meet in Catholic churches in New York. So what happened– I want to cry when I think about it– all the people in Dignity just got candles. It was like just as it was becoming evening, and so there was a procession, a silent, candle-lit procession, around this very big block in New York, and it was silent, and I saw that. It’s so weird, it moves me now to think about, because I suddenly thought, Oh my God, that’s how I’ve always felt. That they didn’t want me there, that they drove me out. So, I think that every time I go near Catholicism, I have this part of me that feels drawn and part of me that feels like I’m just being wrong as a female, being wrong as someone who was queer and didn’t know that’s what she was.

It seems that you write differently about alcohol in this book than you have in past books. Do you feel like your relationship to alcohol, or your way of thinking or writing about it has changed?

I think alcohol isn’t the same for everybody. But some part of me knows that the abuse of alcohol is so widespread that maybe there is something inherently wrong. In the middle ages, supposedly the peasants had no access to alcohol, except on holidays when they were given alcohol, and everybody would drink themselves into oblivion and have wild sex. They might have had it at something like a harvest festival or whatever the medieval holidays were, but the rest of the time, they just didn’t have it. There was no way to get to it. I mean maybe the rich people, like kings, always had wine and mead. I think it’s probably been forming culture forever. I mean, how many babies were born out of the use of alcohol? How much choice was conscious? I don’t know. It’s interesting to think of it as rot. It’s not nice, fresh weed. It’s old. It’s other drugs, like psychedelics, fungus, it’s all really weird, to think about the planet’s deformation of organic things that go into our system. It’s very interesting, the Irish, Native Americans, certain groups get accredited with being the huge alcoholics. You know, there is something to it.

I have a theory, and it’s in one of the books, about what it means to be a prisoner on your own land. What it means to live in an occupied country– does that make one more vulnerable to alcoholism? In the same way that Native Americans didn’t have small pox, they didn’t have alcohol in excess and so there was no genetic way of holding it. Then, I think of the Irish diet, and it was so bad, that who wouldn’t go insane on alcohol, maybe beer or Guinness was just a part of what you got to eat, what you could have.

I think that it’s strangely become wrapped up with this image of the poet, as well. The poet is, you know, a crazy drinker, taking drugs. I wonder where that comes from.

Yeah. I think it’s the fringe. You know, there’s the town drunk, the person on the edge. There’s the person falling down at the party. There’s a person who’s one of us but doesn’t quite belong, doesn’t live in a regular way. I know when I first entered the poetry community, I suddenly realized I had total permission to do the thing that I already was. Because I was already an alcoholic when I got to New York when I was twenty-four, but I suddenly saw it as a professional. It was like, this works here. There was such widespread alcoholism and drug addiction in the community. But again, it was so related to poverty, too. I mean, Allen Ginsberg was supporting so many people at the end of his life. When I went to Ireland and did some research I found that the Myles came from close to the border and they had very bad drinking. That part of Ireland was really bad. On the other side of the family, from the south, the drinking was not so bad. And it had to do with the land, people said, that it was horrible rocky land on the border and beautiful, good farming land in the south. So, alcoholism wasn’t so widespread, but then you think, it’s a kind of deprivation, too.

It’s always tied up in class.

And wellness.

Right.

But it was fascinating too, when I got sober, to really understand and find things, and learn there are water poets and there are wine poets, and that I could be a water poet. Which is to say, to try to have some clarity and not be altering what there is all the time.

Was there something about that clarity that was scary for you? Do you think that drives a lot of people to wine?

Yeah. Well, it was scary because I didn’t have it. When I stopped drinking, my intention was to have clarity, but in fact my brain was scrambled and very confused, and I had to get used to this new apparatus. It didn’t come easy. And I had to learn how to write again inside of this and trust that it could happen. When I first got sober, so many people were like, Can you still write? And the same with sex. Gay people especially, gay men most of all. I know so many gay men who had the hardest time getting sober, because they couldn’t have sex anymore. They had never had sex without alcohol.

To end on a high note– dogs. You’ve had two pitbulls. Do you think there’s something special about the breed?

I do, I do. I mean, I intended to have an easier dog, this time, but this dog came to me through a series of accidents. I mean, they’re just an adorable breed. Their faces are so gorgeous and gnarly and loving and intense and ernest. They just have this visage.

Myles with Rosie. Image via the author.

Absolutely.

And having a dog affects your writing. I felt like having a dog de-centered the writing, and actually this book has been a real shift for me, because, supposedly, finally, I’ve written a book about something that’s not myself, and that’s true and not true. But I think it’s my most experimental book. There was the period of her living and dying, which was very clear and I could write about that. But when she was gone, it was like- How do I fill this gap? I kept something throwing out and then having to catch that and then throwing something else out and having to catch that and kinda giving myself multiple assignments. So, it’s a kind of dog Frankenstein. It was like, I didn’t make the dog up, but I made the book up, and it was an amazing experience. The first time I’ve ever claimed a book to be a memoir ends up being a filled with more fiction than I’ve ever written before. I think genres, just like gender, are just endlessly baggy and wiggly and surprising and are full of opportunities to disrupt, which I took as a kind of call to arms with this book.

Was the content already there, or was it more trying to figure out what to say in a book about the dog?

Well, the content was already there to the extent that I had already absorbed it, but it didn’t mean I knew what it was or where I had it, you know? I always think for me, in many ways, the whole endeavor of writing is about articulating times when you were silent. I think childhood is like a vast like that. It’s like you just turn the camera on, and you just record five years, ten years. There’s a visual track, except you don’t know what’s going on. People are moving you around, you’re a little thing, and you’re full of all this beautiful stuff, and nobody ever asks you what it is. I think so much of being a writer and being an adult is putting a voice track, an articulation track, on that visual. What was your question? It was a good one.

I think genres, just like gender, are just endlessly baggy and wiggly and surprising and are full of opportunities to disrupt.

Just about the content of the book.

So, I knew dog, but there was so much in me, that when I began, all I knew was that they were dying, and that I wanted to write a very kind of punk dog book. I was going to do the harrowing thing. You know, I’ve mentioned this a bunch of times when I’ve talked about this book, but– when I came to New York, Frank O’Hara was the ghost of New York; he had just died like eight years earlier, and people were endlessly introduced through their connection to him and who Frank was. One legendary story was that his friend, the painter Larry Rivers, at his funeral got up and told people just what Frank looked like on his deathbed– the tubes and the bloated, and you know, this was a man who was so beloved. So he just gave them this harrowing picture, and I’ve always been fascinated by that gesture. Is it performance art? Is it like a eulogy? Is it a kind of sculpture? It was so many things; it’s kind of an assault on the tender feelings of the community. Yet, that was totally what I meant to do with Rosie. I thought, I’m going to write that harrowing account. I’m not going to give you a sentimental dog book. Then it stopped, because I think so much is trapped in your muscles and in your joints. Like, we just save all these emotional memories. I had to keep being the purveyor of the assignments that would then draw them out, even though I didn’t know what they were.

That’s interesting that you wanted to kind of buck sentimentality. In terms of dog literature, I think sentimental is probably way up there.

Oh yeah. You know, for me, I’m always starting with some kind of joke, and I think my joke was this, that I’m doing such a dumb book. I think that it’s kind of my smartest book, because maybe the body is dumb. I mean, the body is the dumb holder of all our dreams and ideas.