A Free Press Crusader Like No Other

by Chalachew Tadesse / June 7, 2018 / No comments

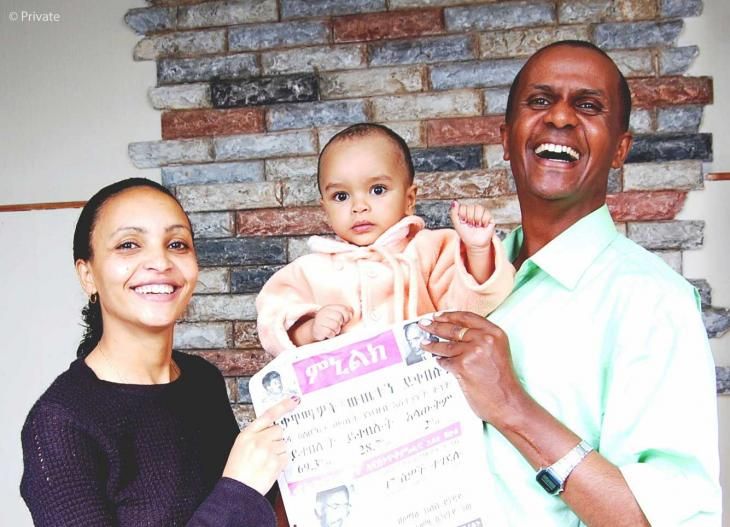

Image via the author.

Not to write about Ethiopian journalist Eskinder Nega during this momentous period would be a disservice to my column. Eskinder is a veteran editor, columnist, blogger, pro-democracy activist, and prisoner of conscience. Most of all, he is one of the pioneers of the free press movement since the mid-1990s and a veteran free-press champion par excellence. In a career that spans more than 20 years, he was in and out of prison nearly ten times. Needless to say, he has no match vis-à-vis his fearlessness and selfless defiance in the face of torture, inhumane treatment, incarceration, witch-hunt and other forms of punishment.

It was just last February that Eskinder was pardoned from a seven-year incarceration along with several thousand political prisoners.

- This column’s topics will include literature, art, education, history, and political culture in Ethiopia, as well as society and politics in the Horn of Africa. Moreover, I will address the tribulations of journalists and the ill-fated constitutional right of freedom of expression under Ethiopia’s deceptive authoritarian regime. I will try to be the voice of the voiceless, be it persecuted journalists at home or exiled journalists abroad. These themes will make Ethiopia’s uniqueness and absurdities evident.

- Chalachew Tadesse is an Ethiopian journalist and columnist. He has previously worked as a full time journalist for The Reporter and The Sub-Saharan Informer English newspapers. He was also a columnist for the much-acclaimed Fact magazine, before the Ethiopian regime closed it in October 2014. A political science student by training, he works as a university lecturer and is known for his sociopolitical commentaries on the Ethiopian private press.

Since 2015, Ethiopia has been in political turmoil. A series of violent anti-government protests plunged it to being an unprecedented political crisis. As the unrest intensified, the ruthless security forces killed hundreds of peaceful protesters. A state of emergency was declared twice in less than two years, putting the country under a quasi-military rule. More than 10,000 people were detained. Above all, internal squabbles surfaced from within the authoritarian ruling coalition, the Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), threatening its survival.

At the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, the embattled government partially gave in. Thousands of political prisoners were released from prison. A lame duck prime minister resigned only to be succeeded by the unlikely young Prime Minister Abiye Ahmed who’s from the same ruling party. Not a single journalist remains in prison now, yet only three newspapers are in circulation for 100 million people.

Pardoned or not, Eskinder owes his release solely to the uprising against tyranny.

I met Eskinder for the first time at an event in a foreign country organized by Amnesty International to celebrate this year’s World Freedom Day. Deservedly, he was Amnesty’s guest of honor. Admittedly, my handshake and brief conversation with him was as emotional as it was evocative.

Eskinder’s story is a story of audacity, ordeal and hope that perfectly captures the long crusade for freedom of the press, and democracy as a whole. So did I rightfully pen this piece.

Ordeal and Audacity

Rewind to 2005. Under Ethiopia’s late autocrat Meles Zenawi, the country’s first relatively free and fair election was conducted. Meles, however, subverted the process and arrested more than 130 opposition politicians, rights activists and journalists including Eskinder and his wife (also a journalist). Ethiopia’s hope for a democratic transition through the ballot box was effectively aborted.

Eskinder and his wife had a tough time in prison in part because his wife had to give birth to their first and only son. One can imagine the emotional pain the couple endured.

When set free 17 months later, Eskinder stayed at home, unlike many other inmates who went for exile. Instead, he tried to get his publishing license back, but to no avail. Soon, at opposition party forums, he resorted to blogging and making speeches, renewing his harshest criticisms of the regime’s increasingly excessive authoritarianism.

In one of his articles in 2011, he asked if Ethiopia was ripe for an Arab Spring style of revolution and warned that would be the case if the government didn’t make an urgent democratic opening. Apparently, Meles was infuriated because “Arab Spring” and “Color Revolution” were the twin nightmarish monsters that haunted him at the time. Due to that article, Eskinder was arrested, and he was subsequently convicted to 18 years in jail for bogus terrorism charges by a kangaroo court. Alas, exercising his right to freedom of expression made him one of the first victims of the new Anti-terrorism Proclamation.

Defiant as he is, Eskinder wasn’t silenced even in prison. Regardless of the odds, he managed to smuggle some of his prison letters and notes out of Kaliti Prison on a few occasions. “Letter from Ethiopia’s Gulag,” which was published in The New York Times in 2013, and “Letter to My Son” were particularly notable. Both shed light on his intellectual expanse and steadfast moral conviction vis-à-vis liberation from oppression.

To defy all odds in prison by penning down illuminating thoughts is simply extraordinary. Quite expectedly, armed federal police officers always stood beside him every time he talked to visitors just so that they could hear verbal conversations and control body languages. How he managed to get pen and paper in the first place and, above all, to secretly transmit written scripts to trustworthy couriers is mostly a mystery.

Little wonder, therefore, that his crusade for free press and democracy didn’t pass unnoticed. International rights organizations regarded him as a prominent prisoner of conscience. Rightly so indeed! He won international awards to his name. International solidarity was so strong that his name was kept in the spotlight despite the regime’s intransigence to heed to the concerted calls.

Most recently, before pardoning him, the authorities tried to coerce him to confess in writing that he was a member of an outlawed organization long labeled by the government as terrorist. This was an outrageous and wicked double standard that he out-rightly rejected. As the news spread on social media, they had no choice but to free him unconditionally a few days later.

Even freedom from prison is no diversion from the noble cause that Eskinder holds dearly. With a renewed zeal, he has continued calling for an urgent transition to democracy, which put him in detention for two weeks again. However, he once left the country only to return soon afterwards. As I write this, he is visiting his wife and son in the US where they got political asylum shortly after his incarceration in 2011, and he still vows to go back to his country. In his “Letter to My Son,” he resolved that anything short of achieving final freedom would be, for him, an “impoverishment of our soul.” Truly, he has an exceptional perseverance that helps him walk the talk.

I am, like many others, impressed by his humility, humor and conciliatory tone. In his interviews, he sounds as if he didn’t endure any agony. One can hardly sense hatred in him. Ironically, solitary confinement might have given him an opportune time to develop all his strong qualities. Now, more than ever before, he sees the nonviolent crusade for “liberté, egalité, fraternité” as a higher moral cause, a lifetime conviction. Absurdly, though, he now believes that journalism and political activism should go side by side. Not quite impressive, unfortunately.

Old Memories and Confessions

Admittedly, most of Ethiopia’s infant press in the 1990s and early 2000s was “gutter press,” an excuse that the government used to justify its relentless press crackdown. Eskinder started as publisher of the local-language newspaper Ethiopis, and in the early 2000s I remember he owned three local-language weeklies, namely Menelik, Satenaw and Askual.

Truth be told, however, his tabloids were typical of yellow journalism. I still have a vivid recollection of them; they mainly focused on spreading rumors and politically motivated fabricated news with ethnic-hatred undertones. It’s no wonder I myself and many other newspaper readers saw them with much detest. Few newspapers fared better than his of course.

Much later, I learned that Eskinder had been adept in journalism all along. Interestingly, I also came to realize that he had been educated in the US for much of his youth but had returned to Ethiopia to practice print journalism following the new freedom of press and abolition of censorship enshrined in the new democratic constitution. So I still wonder why he thought “gutter tabloids” would help his country break the shackles of authoritarianism. Yet I don’t pretend to speculate on why.

In any case, I still believe his contribution to the embattled free press in terms of active professional journalism remains negligible. In hindsight, I also suppose that he might have regrets vis-à-vis the legacy he left as a journalist, editor and publisher.

The other memory I have of him is as personal as it is professional. In 2002, my colleague and I had an exclusive interview with autocrat Meles Zenawi for our English weekly Sub-saharan Informer. When we published the long interview, Eskinder was quick to label us in one of his gutter tabloids as “ruling party cadres working under the guise of free press,” merely because of having an exclusive interview with the autocrat. An outrageous defamation that was quintessential of most free press outlets! Yet we’re astonished for two reasons: firstly, he didn’t ask us why the autocrat was willing to talk to an independent press outlet for the first time, and secondly, to be falsely labelled accordingly by a fellow free press journalist was, to say the least, beyond our imagination.

For these reasons, I had a negative impression of his personality for a long time.

From time to time, however, I saw Eskinder become a seasoned prominent advocate of freedom of the press and democracy who was seen by many with high regard. As I learned more about his selfless devotion to freedom of press and personal attributes, my impression fundamentally changed for the better. Over the years– in particular after the 2005 election debacle– he has turned out to be an unmatched icon of freedom of the press and liberty in his own right. Rightfully so indeed!

I’ve yet to excuse him for his role in gutter press, though. As to his mischaracterization of us, I forgave him because I was convinced that his misguided judgment emanated from the general belief that Meles wouldn’t have sat with a free press publication that he indiscriminately loathed and waged a war of attrition against. Unfortunately, that interview was his first and only interview with the free press.

As I said earlier, Eskinder foresaw a political tsunami in Ethiopia several years before. Even in his “Letter To My Son,” he penned: “Tyranny is a function of fear: the terror of state violence, the menace of imprisonment, the dread of imposed penury.” At the time, I regarded his prediction as political naivety, to say the least, essentially for three reasons: the polarizing effect of ethnic politics, EPRDF’s all-controlling tentacles, and the heavy-handedness and indiscriminate use lethal force by security forces.

A year later, a mass anti-government uprising engulfed the country to the surprise of most of us. Perhaps to Eskinder’s astonishment, too. Collective fear was finally overcome, and a defiant mood of liberation from oppression has since filled the air. Eskinder was vindicated.

Having said all this, let me state that even a measured criticism of Eskinder’s past misdeeds wouldn’t be politically correct at this moment. In fact, that would also invite awkward personal attacks from different corners. Thanks to the pervasive state repression, most Ethiopian social media users have become deeply intolerant of opposite opinion. Eskinder’s fans are no exception, although ironically, Eskinder isn’t in opposition.

A New Dawn or…?

What awaited Eskinder is a country at a critical political trajectory. Qua Vadis Ethiopia? is a question that few can safely speculate about. Quite interestingly, Eskinder optimistically believes that Ethiopia is now at the dawn of a genuine democratic change. And so do many people. In a major break from the past, the new prime minister has also brought back long-ditched political languages into the national lexicon, which resonates quite well with most Ethiopians.

Here’s the problem though: Several concrete political reforms are yet to be taken. The government hasn’t shown real steps to rescind the draconian laws– in particular, laws relating to press freedom and civil society although the government pardoned charges on two dissident Ethiopian media houses based in the United States. But some small moves have been initiated to amend the Anti-terrorism Proclamation used to convict Eskinder for 18 years behind bars. Besides, the state of emergency decree that prohibited inter alia peaceful demonstration and assembly has been lifted in early June. Justice for peaceful protesters who were killed arbitrarily by security forces still however remains almost a luxury, so to speak.

Without fundamental political reforms, the status quo will surely be short-lived.

Will the EPRDF-led hegemonic government, which is mostly considered incorrigible from the core, tolerate Eskinder’s call for a free and fair ballot box to pave way for a smooth democratic transition? There’s some hope, but much uncertainty, because what we’re seeing now is too much heat with little light. Will Eskinder stay free from prison to rally the people behind the long overdue cause that he has championed for? Time will tell. At last, let me emphasize that the road to achieve democracy will be long and bumpy, but the fact that Ethiopia was the only independent African country from colonialism– unlike all other African nations– is certainly no curse that makes Ethiopians antithetical to democracy and free speech.