Back to the Body: An Interview with Natalie Diaz

by Abigail Meinen / February 22, 2018 / No comments

Natalie Diaz. Image via Blue Flower Arts.

Natalie Diaz knows the power of bodies– the ways that they move, wound, survive, shape, and are shaped by language. Born in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, on the banks of the Colorado River, Diaz grew up playing basketball. She earned a BA from Old Dominion University, which she attended on a full athletic scholarship. She then played professionally in Europe and Asia before returning to Old Dominion to earn and MFA.

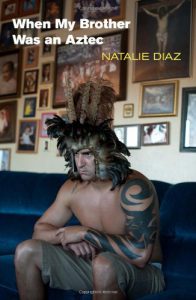

Her first poetry collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec, was published by Copper Canyon Press, and explores her family’s experience with addiction, intimacy, and her Mojave heritage. She is a Lannan Literary Fellow and a Native Arts Council Foundation Artist Fellow. She currently teaches at Arizona State University and directs the Fort Mojave Language Recovery Program, working with the last remaining speakers at Fort Mojave to teach and revitalize the Mojave language.

Diaz visited Pittsburgh in September of 2017 to read her work as part of City of Asylum’s annual Jazz Poetry Month. She spoke with Sampsonia Way about her language revitalization work, her poetry, how we talk about anxiety and what it might have to tell us.

You have talked before about lexicon as a kind of anti-witness. What parts of lexicon have become really important to you now? What words, phrases, or other parts of lexicon are you interested in at the moment?

It’s a really good question because I think I’m still trying to figure out what that landscape is, and also trying to defamiliarize the word lexicon, to let it be something new. Usually when you think of lexicon it’s just that vocabulary list. Considering that my tribe’s language was silenced for so long, what I realized, through my language work, is that people had collected those vocabulary lists, our Mojave lexicon, and then left with it. They went to their universities and left our bodies behind. That’s the part that I find myself kind of enthralled with. Enthralled even in an etymological sense- it kind of puts a hole in you, in a way.

I think I am trying always to return back to the body because as an indigenous person, as a Latina, as a queer woman, I haven’t been given the permission or the space, to be fully in my body. Things like pleasures, and the autonomy of pleasure, and ecstasy- those things weren’t allowed for us. We weren’t supposed to fulfill those things. So for me, it’s always about trying to come back to the body, trying to say- How can I constantly return to the body, even when it’s uncomfortable, so that I have the possibility of those things? And that is where I am mostly situated right now, just kind of wandering around in the space of my own body. I am writing a lot of love poems. But I’m also trying to rethink the way that I held the body in my first book: the body of a brother, or the body of a loved one. I’m trying to actually let that love lead the way, in that kind of exploration of the body. I really am committed to the idea of- what if I try to treat every body on the page like the body of the beloved? Somehow that also makes it possible for the speaker, and then me, the poet, to do that as well. It feels like a very generous space, and it is also not the most comfortable space to be in, I think.

I am trying always to return back to the body because as an indigenous person, as a Latina, as a queer woman, I haven’t been given the permission or the space, to be fully in my body.

You have talked about your experience with anxiety also, and I think so many oppressed bodies find themselves dealing with that. I think that part of anxiety is a kind of panic or terror of the very experience of embodied-ness, and so I was curious- how do you navigate so much thinking about the body with the constant anxiety that you feel?

I think that is interesting to think about. I wonder a lot about anxiety. It’s something that is inhibiting for me. My mornings are tough because of anxiety. Plane rides are tough. We all have so many anxieties. Right now we suddenly have an American anxiety, whether you are talking about pharmaceuticals and the rise in the number of people being treated for anxiety, or you are talking about our government. But what is interesting to me is that I feel like I have had those anxieties in me. They aren’t new to me. What I find frustrating is that we don’t have a lexicon to talk about it. We have things like, “Now more than ever,” or, “Not my president.” It’s almost like we have stopped talking as body to body and we have started just using slogans or memes. Part of this, I think, is the social media train that we are all aboard. But I am wondering if anxiety in some ways is just my body in the wrong place. Suddenly, I am no longer shrinking. Now I am taking up space, and I realize that space doesn’t want me there, or wasn’t meant for me, and the energy of that is very palpable. But even to acknowledge that, to realize- Okay, I don’t feel good- it’s never been something I’ve done in a poem because I thought I always had to make the metaphor for that. But what if I just let language work in all the ways that it can? Sometimes me writing is simply to just say, I don’t feel good. I don’t know what else to do except to say, that I don’t feel good, and maybe give an image associated with that. I think it’s interesting to figure out what poetry can do when you don’t make it be poetic. Because really, what is it? It’s language, it’s emotional language, it’s emotional energy, and it’s maybe one of the truer ways that we can talk. There’s a certain vulnerability that you have to embrace to say- I am going to sit here, and talk and think about something that has a possibility to be extremely uncomfortable, but also has the possibility to end in joy in some way.

But I am wondering if anxiety in some ways is just my body in the wrong place. Suddenly, I am no longer shrinking.

To talk a bit more about language and what it can do, what does your work with the Mojave Language Project look like now?

I no longer do the language work on the reservation, but what I am doing now is working in the archive that I collected with some of my elders. I am trying to find ways to make it accessible to them, but also to let it be as complicated as it is so that when people are ready to come to it, they can come to it. It’s kind of a paradoxical space. I have all of these stories and things that my elders have shared with me, and you need a certain amount of language, but you also need a certain kind of patience to be able to come to them and let them inhabit you.

Back on the reservation, my Mojave tribe is doing a program with learners. They are trying to do something almost like a language nest: they took five adults and they are trying to immerse them as much as they can in the language, which is tough when there aren’t fluent speakers, other than a few elders who don’t really have the energy to lead a class and to be there daily.

One of the reasons why I have been excited to go back to Arizona State is because that is where my language work began, with some of my mentors there who had worked with indigenous language recovery. I learned a lot from them, and it is a place where I feel like I can put the archive so that it’s available when my fellow members of the tribe and family members want to come to it.

Diaz reads at City of Asylum’s annual Jazz Poetry Festival. Photo by TJ Murphy.

That is really exciting. Was there anything in that project that surprised you? What came out of it that you weren’t expecting going in?

Oh, so much. I think I am a much different person than I was when I began working with the language and working with my elders. I think time is very different for me now, and the idea of patience. Patience is actually not the thing I want to have. I want to move on the other side of patience, so that suddenly, time is different. To be able to sit in silence, and to not need to fill silence. It actually taught me a lot about conversation, at least the kinds conversations that I would like to have. Sometimes they are going to be silent, and we are just going to acknowledge what was said. We might think, Oh, I don’t know if I have ever thought about it that way, and I’m not even sure if I agree with it, but I’m going to just kind of let it move in my body in a way. My elders were very much like that, they would talk, sometimes they would talk for hours, and then be completely silent. I always thought I had to fill that in, and then I realized I didn’t, because our bodies were actually talking. It’s interesting to think about silence as being a type of speaking, and maybe even a more important type of speaking. It’s crazy because on the page you recognize that. As a poet, you know that white space is not nothing. It has a purpose, it has a texture, it has a sound, it has a space. So that was one lesson, that I don’t know how else I would have received.

Patience is actually not the thing I want to have. I want to move on the other side of patience, so that suddenly, time is different.

Also, just that idea of the body– I learned so many ways of considering my body. In Mojave you don’t say, “He was walking down the road.” You would say how he was walking, putting you back into the texture and purpose of the body. There’s no generic for like, “He was walking.” You would say how he was walking, or where he was walking to or where he was coming from. Intentionality is something- as a poet you think that you have it and suddenly you realize- Oh no, language can be very intentional very precise even though it’s so far from perfect, and even though it’s falling short.

A really emotional thing that happened is I had an elder who would be the person I would go to, my teacher, Hubert, and I would say, “How do you say this?” or “How do you express this?” or “What is the word for this?” and sometimes he would say, “There’s nobody left for me to ask.” To feel his loss and one, to realize that my loss will never be as deep as his loss, but also, it was a really strange flex back, or ripple back to see his grief hit him and then come back through me and to suddenly realize what is passed from body to body, what is passed from generation to generation. I think that is lucky because I don’t think a lot of Americans get the chance and the time and the space and the non-rushed hour to feel those things. So I guess, to answer your question, I found that time is almost like an accordion of sorts. Instead of being linear or instead of being something easily measured, it can just kind of flex in all these different directions.

I think that when most people think about poetry and then think about the embodied experience, those things somehow seem incongruent in a way. There are a lot of embodied art forms, but writing on the page maybe isn’t the first one that comes to mind. Why does it make sense for you to portray the embodied experience on the page?

Diaz’s debut collection, When My Brother Was An Aztec, was published by Copper Canyon Press and won an American Book Award in 2013.

I grew up in a very physical art of basketball, and also my family is very large and we grew up in a very small space– like in two bedrooms. So touch is something that is very important. It’s one of the ways that we communicate best sometimes.

I also think that one of the reasons why we have gotten so far away from the body is because poetry has in many ways become a book, or a font. People always ask- “What font are you using?” and there are even places that don’t let you use certain fonts. We do most of our poet-ing on a computer. Whereas, on the tour [of Sampsonia Way] this morning, Hannah talked about the House Poem-Huang Xiang’s house with his poems painted on it. She said “Huang Xiang read his house.” And I thought, That’s what’s missing! It’s like when you write in a notebook, and just suddenly understand-Oh the pen is my hand. It’s my body. And even though these are just thoughts or wonders, it’s the energy of my body that I am trying to put on the page. So again, to think of letters as physical, as bodies.

The alphabet is a body, that is carrying our bodies. One of the things I’m really interested in doing right now, it might seem a little bit silly, but something that I am doing with my students is I want them to write all the iterations of a letter. Now we just have the letter A or the letter B, but I want them to paint with a big brush and India ink, and suddenly to realize, Oh this is an art form. A letter is an art form, you know? It took an amount of time to draw it, to find pigments to create something that would last on a wall, or on a tablet, or on a scroll. I think we’re not far from returning to that, even though it seems like we are so far down the road from it. It feels lucky to have that consideration, because I think what it allows me to do is to understand still, the risk of feeling on the page. Even reading poems from my first book, or reading new work I’m doing now, whether it’s about something traumatic or grotesque or about love, it still feels like work to me. It still feels like emotional work. I think that is what has let me stay in poetry. It’s also the same thing that drew me to basketball. I understood the body that was involved and what was being asked of the body, and that sometimes, it was a little bit impossible, but you could still end up somewhere near to impossible, near what you tried to do.